An excerpt from the first chapter of the book "Brunelsky's Dome", by Ross King. Dvir publishing house 2003.

Ross King

Direct link to this page: https://www.hayadan.org.il/brunellschisdome.html

It's not always convincing, sometimes it creaks, but it usually works well

by Dan Daur

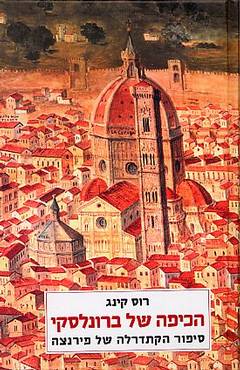

Brunelleschi's Dome The Story of Florence Cathedral

Church of Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence

Ross King. From English: Ronnie Reich. Dvir Publishing, 183 pages, NIS 74

"Heaven willed... Filippo will leave to the world the largest and noblest building, the most beautiful of those built in both the new and ancient times", so writes Giorgio Vasari in "The Life of Brunelleschi" about a hundred years after the death of the one who is considered, perhaps rightly, "the father of architecture" The Renaissance". Brunelleschi did not design the cathedral of Florence that is still associated with his name, nor even the dome which is undoubtedly one of the greatest engineering achievements of all generations. Arnolfo di Cambio, the architect of the "Old Palace", laid the cornerstone for Santa Maria del Fiore about ninety years before Brunelleschi's birth (1377), and Neri di Fioravanti, who built the arches of the "Old Bridge", was the one who outlined the shape of the pointed dome , built on an octagonal base, about ten years before he was born. But Brunelleschi is the man who found a way to build the dome - a double brick dome, the largest in the world (about 43 meters in inner diameter, 55 meters between the two farthest points in the octagonal base of the outer dome, 55 meters high including the drum on which it stands, and a little over a hundred meters height from the ground, but it is difficult to find two sources that give the same numbers), without external supports like those in Gothic churches ("floating tests" in the language of the book), and without internal scaffolding.

But how exactly did he do it? This is an engineering puzzle, and if I understand correctly, its solution is still in dispute. There is no detailed documentation of the work, and no drawings that can teach us much (which is true by the way of the drawings in the book). Massimo Ricci, a Florentine architect who has been working for years on building a 1:5 model of the dome (not mentioned in the book, but very accessible on the Internet), claims that he found it - partly with the help of a drawing by a contemporary rival of Brunelleschi, who tried to show that it was impossible to What his opponent did - it was enough in the hollow frame that connected the inner and outer dome, and at the particular angle at which the dome was arched, to do it without a center and with the devices of that time. In his opinion, there is no real structural need for the stone and wood "chains" that interrupt the brick structure, and that they were mainly used to calm the concerns, whether of others or of Brunelleschi himself. Matteotti, an Italian engineer who lives in Australia and writes a lot about historical engineering achievements, accepts his opinion and therefore concludes that Brunelleschi was not really a Renaissance man but rather a late Gothic type, with a fondness for Roman buildings, who worked mainly according to intuition: "He had an extraordinary structural sensitivity, but basically He guessed something and hoped for the best: in the case of the Santa Maria del Fiore dome, he guessed right!"

Ross King also guessed correctly, and managed to turn a technical subject - it seems that the average tourist in Florence is willing to settle for ten minutes of quasi-explanation - into a global bestseller.

Not necessarily thanks to what he writes about Brunelleschi the man, about whom the material examined is extremely weak. Like Vasari, King calls him Filippo most of the time, but even after reading the book the man remains quite unknown, so it's hard for me to follow in their footsteps. There is probably no debate about his uninspiring outward appearance, but was he really liked by those around him as Vasari claims, or a quarrelsome and closed and suspicious man, as King concludes, probably rightly, from the few documents that have remained since then? About the decisive years in his development - from the time he lost to Ghiberti in the competition for the gates of the baptistery in 1402 until he returned to Florence in 1416 - we know nothing.

Part of the time he hung out with Donatello in Rome, and as King writes he "might have" (kind words for King, and Zari sounds more positive) interested in the Pantheon which "might have provided him with the proof". On the other hand, he "might" also visit Turkey or Persia (where "one can find systems of combined bricks similar to those in the dome in Florence..."). In any case, the more interesting chapters in the book tell about side affairs, such as the vessel he designed to bring marble from Carrara up the Arno River, a vessel that earned the name "the monster" and sank all its precious cargo on its maiden voyage; The failed dam he built in the war against Lucca, or the conflict with the builders' guild that landed him in prison.

What adds perhaps more is the wise way in which King combines between the technical and biographical chapters brief historical reviews, background descriptions, and necessary information about the living conditions of the workers in the dome, the bohemian carelessness of the artists, the status of the son, the splendor of the religious processions, etc. Sometimes there is a feeling of unnecessary condensation (such as the chapter on Tuscanelli or the end of the chapter on Rome), it is not always convincing - for example when he says that the pace of life at the beginning of the 15th century began to increase when they went from dividing the hour to sixty minutes instead of forty; He relies here on one rather old general book and ignores what is fairly well known, that even in Galileo's time there was no minute clock. Sometimes it creaks, like the transition from the rings of the dome to the nine circles in Dante's Hell, with the sentence "This is also a fitting comparison, since in 1428, shortly after the arch of the first ring was completed, Filippo faced the beginning of his own descent into Hell." Here and there it's really annoying, like his addition to Vasari's sentence that opens this list, "almost like the Christian Jesus who came down to the world to redeem man". Which allows him the dumb conclusion "Yet Philip was neither a god nor an angel, but only a man and in his undisputed genius, Renaissance writers found their proof that modern man was as great as, and in fact capable of surpassing, the ancients, from whom he drew his inspiration" (a sentence that also teaches about the translation, which is apparently reliable). And there are odd mistakes too - Giovanni da Prato, Brunelleschi's bitter rival, was born too late to be Dante's teacher - but generally this mixture works well.

Dan Daor's book of translations "108 Chinese Songs" was published by Hargol

An excerpt from the first chapter of the book "Brunelsky's Dome", by Ross King. Dvir publishing house 2003.

6/11/2003

On the nineteenth of August 1418, a contest was announced in Florence. where the magnificent new cathedral, Santa Maria del, has been under construction for more than a century:

"Anyone who wishes to create a model or plan for the roof of the main dome of the cathedral under construction by the Opera del Duomo for the supports, the scaffolding or anything else, or any lifting device related to the construction or improvement of said dome or vault - shall do so before the end of September. If he uses the model, he will be entitled to a payment of 200 gold florins."

Two hundred florins was a considerable sum of money - more than a skilled craftsman might earn in two years' work, and thus the competition attracted the attention of carpenters, builders and plasterers from all over Tuscany. They had six weeks at their disposal to build their models, draw their plans, or simply - offer ideas on how the dome of the cathedral should be built. Their proposals were supposed to solve a variety of problems, including how to build a network of temporary wooden supports to support the dome's stone structure on its feet, and how to lift blocks of stone, sand and marble, each of which weighs tons of sympathy. The Opera del Duomo - it is the ministry of works in charge of the cathedral - assured all those who approach the competition, that their efforts will receive "friendly and loyal attention".

At that time, dozens of other craftsmen were already employed at the construction site, which spread out in the heart of Florence: carters, bricklayers, leadsmiths and even cooks and people whose job it was to sell wine to the workers during their lunch breaks. From the square surrounding the cathedral you could see people carrying bags of sand and lime, or those climbing on scaffolding and wicker platforms that rose above the neighboring roofs like a sloppy bird's nest. Nearby, a blacksmith shop for repairing the tools of the workers blew clouds of black smoke into the sky, and from dawn to dusk the air was filled with the sound of blacksmiths' hammers, the roar of bullock carts and loud instructions.

Early fifteenth-century Florence still had a rustic appearance. Within its walls one could see wheat fields, orchards and vineyards, and flocks of sheep were driven through its streets to the market near the baptistery of San Giovanni. But the city also had a population of 50,000, quite similar to that of London, and the new cathedral was designed to reflect its importance as a large and powerful trading city.

Florence became one of the most prosperous cities in Europe. Most of its wealth came from the wool industry, in which the monks of Umilati began to engage, shortly after they came to the city in 1239. Bales of English wool - the best in the world - were brought from the monasteries in the Cotswolds to bathe in the Arno River to Sarkan, to be spun

For threads, weave them on wooden looms and dye them in spectacular colors: red-vermilion made from the cinnabar collected on the shores of the Red Sea, or bright yellow made from the oaks that grew in the meadow near the town of San Gimignano, which sits on top of the hills. The product was the most expensive and most desirable fabric in Europe.

Because of this prosperity, Florence in the fourteenth century experienced a building boom the likes of which had not been known in Italy since the days of the ancient Romans. Quarries of golden-brown sandstone were opened near the city walls; Sand from the Arno River, dug up and filtered after every flood, was used to make mortar; Gravel was collected from the riverbed to be used as filling for the walls of dozens of new buildings that continued to pop up in all parts of the city. Among these buildings were

Churches, monasteries and private palaces, as well as monumental buildings such as a new ring of fortifications designed to protect the city from invaders. These fortifications rose to a height of about seven meters and their perimeter was about seven and a half kilometers long. More than fifty years were required to build these protective walls, and their construction was only completed in 1340. A new impressive town hall, the Palazzo Vecchio, was also built, and next to it a bell tower that rose to a height of about one hundred meters. Another impressive tower was the bell tower of the cathedral which is about 90 meters high, rich in reliefs and various marble slab inlays. The tower was designed by the painter Giotto, and was completed in 1359, after more than two decades of work.

But in 1418, the most enormous construction project in Florence still needed to be completed. The new cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore was intended to replace the ancient and dilapidated church of Santa Reparata, and to be one of the largest in the Christian world. Entire forests were required to provide wooden beams for its construction, and huge slabs of marble were transported along the Arno on fleets of ships. From the beginning, its construction had a connection to civic pride as well as religious belief: the cathedral was supposed to be built - so the council of Florence determined - with the abundance of elegance and splendor possible, and when completed, it would have to be "a more beautiful and dignified house of worship than anything that exists in any region of Tuscany". But it was clear that the builders faced great obstacles, and the closer the construction of the cathedral came to completion, the more difficult their work became.

The progress of the work was quite clear. In the past fifty years, a model of the building about ten meters long, to scale, the work of an artist, has been housed in the south spire of the unfinished church, which has killed what the cathedral should look like when it is completed. The problem was that the model included a huge dome - a dome that, if it had actually been built, would have become the tallest and widest dome ever built. For fifty years it was clear that no one in Florence - or anywhere else in Italy - had any idea how to establish one. The unfinished dome of Santa Maria del Fiore thus became the architectural enigma of the period. Many experts held the opinion that its establishment is an impossible operation. Even the original planners of the dome were unable to advise how the enterprise should be finished, they only expressed their belief that at some point in the future, God would provide the solution, and that architects with more advanced knowledge would be found.

The cornerstone of the cathedral was laid in 1296. The first planner and architect was the master builder Arnolfo di Cambio who built both the Palazzo Vecchio and the massive new city fortifications. Although Arnulfo died shortly after construction began, the builders continued to create, and over the next decades, an entire district of Florence was razed to make room for the new building. Santa Reparata, and another ancient church, Man Michele, were both destroyed, and the inhabitants of the area were displaced from their homes. Not only were lives evacuated; to open a space for a square in front of the church. The bones of Florentines who had died a long time before were exhumed from their tombs surrounding the Baptistery of San Giovanni, which stood a few meters west of the construction site. In 1339, the level of one of the streets south of the cathedral, Corso deli Adamari (now Via dei Calciouli) was lowered, so that the height of the cathedral would appear even more impressive to anyone approaching it from this direction.

But as Santa Maria del Fiore gradually grew, so Florence shrank. In the fall of 1347, the Genoese fleet returned to Italy carrying not only spices from India, but also the black Asian rat, which carries the Black Death. Four-fifths of the future inhabitants of Florence would die in the next twelve months, and the city's population dwindled so much that it became necessary to import Tatar and Circassian slaves to alleviate the labor shortage. Therefore, in 1355 only the facade and the walls of the middle hall were built in the cathedral. The interior of the church was open to the heavens. like a ruin, and the foundations of the eastern section, unbuilt,

They were exposed for such a long period of time, that one of the streets to the east of the cathedral was named: "along the foundations.

However, in the next decade, when the city gradually recovered, work on the cathedral was accelerated, and in 1366 the middle hall was completed, and the eastern end of the church, which included the dome, was ready for planning. Arnolfo di Cambio undoubtedly intended a domed church, but no evidence of his original plan survives. At some point in the fourteenth century, a model that created a di cambio for the cathedral collapsed under its own weight - an ominous sign - and was subsequently lost or destroyed. Excavations conducted at the site in the seventies of the twentieth century revealed foundations for a dome designed to have a key of 62 bracha, or 36.22 meters (the length of a Florentine bracha is 58.4 cm, approximately the length of a real human being). With such a diameter, the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore would pass by about 3.65 meters the opening of the dome of the most impressive church in the world, Santa Sophia (in Constantinople (Istanbul), which was built about 900 years earlier by the Emperor Justinianus.

The book therefore tells about the dome that was built in the end and which was fixed forever in the touristic landscape of Florence.

https://www.hayadan.org.il/BuildaGate4/general2/data_card.php?Cat=~~~676177574~~~53&SiteName=hayadan