On the relationship between a common infectious disease in developing countries and a tendency to allergy in developed countries

The prevalence of allergies in the developed world is steadily increasing and is a significant health challenge, but this may be the price we pay for a higher quality of life. According to the "hygiene theory", exposure to infectious disease agents, which is more common in the developing world, protects against allergies. According to this logic, people who live in a relatively sterile environment and are less exposed to infections - may suffer from allergies and other autoimmune diseases, in which the immune system works against healthy cells and tissues. This theory was recently strengthened following a collaboration between scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science, the Haim Sheba Medical Center (Tel Hashomer) and Bar-Ilan University. In a study published in the scientific journal EMBO Reports, the researchers found a connection between bilharzia - a disease caused by a parasitic worm called schistosome and common in developing countries - and the tendency to develop an allergic reaction.

The project was born following a chance conversation between two Israeli researchers at a conference in the United States. Dr. Neta Regev-Rotsky from the department of biomolecular sciences at the institute told Prof. Eli Schwartz of Sheba about her discovery, which reveals how the malaria parasite tricks the immune system so that it will not act against it, by sending out small segments of DNA packaged in tiny bubbles. Prof. Schwartz, who over the years treated many travelers who fell ill with infectious tropical diseases, wondered after the conversation if it was possible that the bilharzia leech uses a similar strategy.

From the top left (clockwise): Dr. Neta Regev-Rotsky, Dr. Yiftach Barshat, Dr. Orli Avni, Prof. Eli Schwartz, Dr. Yifat Ofir Birin, Dr. Tal Menninger and Dr. Dror Reuvani . It all started with a chance conversation at a conference in the United States

People usually become infected with bilharzia when they swim in lakes and other freshwater bodies. The worm penetrates through the skin, matures in the body to its adult form - and lays inside it thousands of eggs, some of which find their way back to bodies of water through body secretions. The larvae that hatch from the eggs infect water snails, multiply inside them and return to the water in their new form, which allows them to infect humans or other mammals and vice versa. In humans, the parasite can cause pain, diarrhea and other symptoms, but it can also incubate in the body for years without causing any symptoms.

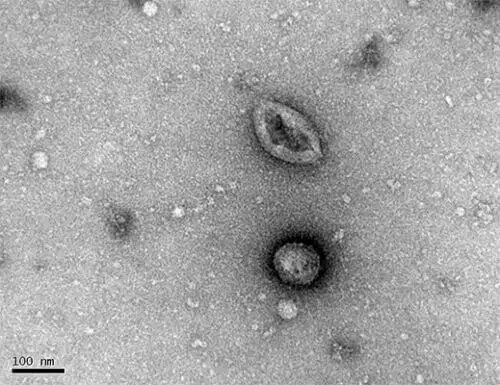

To test whether the bilharzia leech works similarly to the malaria parasite, Dr. Dror Avni of Sheba teamed up with Dr. Regev-Rotsky and immunologist Dr. Orli Avni from the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine of Bar-Ilan University. They adapted the methods developed by Dr. Regev-Rotsky in her research on the malaria parasite to the study of the bilharzia leech and examined under an electron microscope and an atomic force microscope the particles isolated from a culture in which the worm was grown. They found that, similar to the malaria parasite, the bilarzia leech also secretes unique nanobubbles that contain tiny segments of its genetic material, called microRNA. Later, the scientists also located these fragments in the blood of bilharzia patients and saw that the amount of fragments decreased significantly after drug treatment of the disease. These findings strengthened the hypothesis that it is indeed genetic material that the worms secrete.

But in what way do the bubbles released by the worm affect the immune system? The researchers isolated T-type immune cells from the lymph nodes of mice infected with bilharzia, and saw that they contained the microRNA of the worm. Later, they created a system in the laboratory by which they separated the worms and the T cells that had not yet differentiated into different subtypes with the help of a filter. They saw that the bubbles that passed through the filter penetrated the T cells on the other side, and blocked the biochemical reactions that were supposed to help them differentiate into Th2 cells - a subtype that is responsible for activating the wing of the immune system that fights parasitic infection. In other words, similar to the malaria parasite, the bilharzia leeches also send out a sneaky message that prevents the activation of an immune response. These findings explain how leeches can remain in the body for years without the immune system acting against them.

Th2 cells are also known to cause asthma, atopic dermatitis and many other diseases characterized by allergy and autoimmune response. Therefore, the findings also provide surprising support for the hygiene theory: the parasitic infection that suppresses Th2 cells is common in developing countries, and accordingly - allergies and autoimmune diseases are less common there.

Mouse T cells containing nanobubbles (red) that were secreted by the bilaterian

Mouse T cells containing nanobubbles (red) that were secreted by the bilaterian

Bilharzia is diagnosed through a blood test to detect antibodies to the worm, but since the antibodies remain in the blood even after the parasites have been eradicated, it is currently impossible to differentiate between an infection that was and has passed and an active disease. The research findings may lead to the improvement of the diagnosis of bilharzia so that it will be based on the detection of the genetic material of the worm and not on the detection of antibodies. Also, in the future it may be possible to develop a treatment for the disease that will prevent the worms' messages from reaching the immune system. An in-depth understanding of the interrelationship between the bubbles and the immune system will perhaps one day also allow to develop new ways to prevent or treat autoimmune diseases

Dr. Tal Menninger and Prof. Yehezkel Sidi of Sheba participated in the study; Dr. Yeftah Barshat and Boris Burnett from Bar-Ilan University; Prof. Daniel Gold from Tel Aviv University; and Dr. Yifat Ofir Birin and Alia Dekel from the Department of Biomolecular Sciences of the Institute.

More than 200 million people worldwide are infected with bilharzia, most of them in Africa.

More of the topic in Hayadan:

The World Health Organization has recommended the adoption of a new monitoring method for the bilharzia disease developed by a researcher from the Hebrew University

dams

Itching: the mind-numbing sensation

2 תגובות

I asked Prof. Schwartz from Sheba on the phone if it was possible that I contracted bilharzia due to multiple trips abroad and because I stepped on a huge snail during the season and then tried to nurse its fragments and touched it. Due to this question that was in a telephone conversation, he labeled me del parasitosis and wrote in hysterical observations regime... It was unprofessional and hurt me a lot, completely contrary to the first impression he made on me at first. I do not recommend this doctor. He didn't mind putting me at risk in front of the medical world and distorting the information.

An interesting article, but the main line in it is very strange:

"The prevalence of allergies in the developed world is steadily increasing and is a significant health challenge, but this may be the price we pay for a higher quality of life."

The article describes that a certain part of the immune system of people in developing countries (Th2 cells), which is responsible, among other things, for autoimmune diseases, is "knocked out" by lesions, which is perhaps the reason why there are fewer allergies and autoimmune diseases there.

It seems strange to me to call allergies "the price we pay for a higher quality of life".

Because in fact the article says that allergies are "the price we pay for a more functional immune system".

The fact that the immune system attacks the body is a problem that must be understood and investigated, but surely the solution to it is not an immune system that works less well.