The arrangements that elevated the priesthood to the highest status in Judah during the Persian period lasted as long as the priesthood functioned to the political and economic satisfaction of the new control

Part II - The status of the priesthood in the Persian period

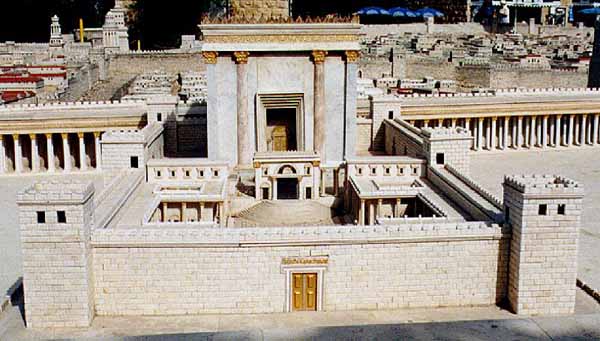

The previous list from Peri Atti was "stuck" in the chronological bar between the end of the Persian era and the beginning of the Hellenistic rule in Judea and marked the organizational and class enslavement of the priesthood in general to the royal institution (the days of the First Temple) and its breakthrough into the upgraded space of the days of the Second Temple as a result of a combination of Persian policy and a priestly initiative led by Ezra the writer. The Hellenistic government was right to accept this situation as long as the priesthood functioned to the political and economic satisfaction of the new ruler.

In the list discussed, from the beginning of Hellenistic rule (312 BC) until the eve of the Maccabean revolt (beginning of the second century BC), the priesthood goes through an almost natural and logical phase of capital-rule, and it gradually begins to integrate into the entire complex process of Hellenization (Greekization) as it was Monarchy for all intents and purposes, when these two lines complement each other.

It all began with the dizzying campaigns of Alexander, the son of Philip II, King of Macedonia, against the Persian Empire. In a relatively short period of time, the Persian Empire collapsed due to the predatory forces of Alexander and he was the heir to the largest kingdom in the world at that time, one that stretched from India in the east to Egypt in the west and Las in the west. Alexander developed an ecumenical theory of control based on syncretism - the hybridization between Greek culture and the "barbarian" one (so in the Hellenic language), and therefore it was convenient for him to approve the pyramid of priestly control that prevailed in Judea. Thus, for pragmatic reasons on one hand and as an expression of support and loyalty on the other, Alexander's successors also continued the ruling line, and especially the rulers of Egypt (Ptolemaeus=Ptolemy) and Syria (Seleucus).

The period of transition between Persian and Hellenistic rule is described in the composition of Kataios Ish Abdira. His composition was published by Hektaius in 300 BC, (and is quoted in Joseph Ben Mattathias's Anti-Apion) and he reports that in 312 BC the famous Battle of Gaza took place, during which Ptolemy I ben Lagos defeated Demetrius the Seleucid, and from that time the army of Syria was given, including Judah, under Ptolemaic rule. As a result of this transformation and the kindness and virtues of King Ptolemy, many good people from the place joined him and went down with him to Egypt. Among them, Hakataius reports, was an intellectual man named Hezekiah, the high priest, and he was 66 years old. Hela was characterized by speaking talent and rhetorical, business and organizational abilities. The Kataios added that 1500 priests in the minyan receive income (priesthood gifts from the people) and manage public affairs.

This is a non-Jewish first source that refers to the High Priesthood, its status, the qualifications of its head and the priests who manage public affairs. The source can be cross-referenced with the image that emerges from the narrator in Ezra and Nehemiah, and its importance is that the Kataios does not describe any other monarchical or aristocratic rule in Judah.

In another passage, the Kataeus relates that after Hezekiah came to speak with King Ptolemy, he gathered some of his friends and read to them a scroll that contained the story of their settlement in Egypt and their constitution in general.

The settlement of Hezekiah and his people deserves to be interpreted as the establishment of a military colony (Katoikia), and it seems that its system of rights was defined through a "written politia", as this contained the terms of the contract for the military service of Hezekiah's people. Cohen's standing at the head of the leadership of a military settlement shows a special kind of organization with a definite religious color (according to Prof. Aryeh Kosher, The Jews of Hellenistic and Roman Egypt, 48, p. XNUMX).

Why Hezekiah did not stay to manage the temple in Jerusalem is unknown. In any case, the mention of the figure of the high priest, but without the matter of inheritance, economic and political status, may indicate that the status of the priestly leadership in those days, as it would become in the course of time, had not yet been established.

A famous ancient writer, Diodorus Siculus (from Sicilia-Sicily), wrote a treatise called the Historical Library, and he often relies on Hecatius of Abdira. Although Diodorus was born in the first half of the first century BC, his words seem to reflect the time of Kataios, or close to it, and he writes: "For this reason, a king will never rule over the Jews, while the representation of the people (=Protesia) is given by the priest who ascends the others in his intelligence and his superior qualities. They call him a high priest" (M. 3).

It is surprising that this writer did not know the history of the monarchy in Judah and Israel, which led him to confess that he never led the people as a king. And perhaps, in a framed essay, what appears to us as the history of the Jewish and Israeli/Samaritan royal house was nothing more than a tiny local control that lacked the accepted dimensions of a royal house.

In any case, whether he erred on purpose or in good faith, it is clear that this author is directing his words to his day, when the high priest's position was high and lofty, one who earned the title of bearer of the Hellenistic "Protesia".

In any case, it is not clear whether the High Priest was appointed/elected during this period for any of his special virtues, or whether by virtue of some inheritance, something embryonic, and/or then Diodorus praises him because of his holiness. In any case, the source is interesting, mainly because it is a text that is not from the "home field", and it can certainly be crossed with the words of praise of Aristeas (immediately below) from this one and Shimon ben Sira (following on) from this one.

Moreover, according to Diodorus, it was Moses who handed over the law and supervision of the laws and customs to the priests. This statement, which probably represents some kind of widespread rumor, indicates how high and exalted the status of the priests was, and especially sacred.

In the Epistle of Aristeas (a minister in the government of King Ptolemy Philadelphus II - 247-283 BC), King Ptolemy is quoted as addressing the high priest in Jerusalem, literally as his soulmate - "King Ptolemy to Eleazar the High Priest, peace and health..." (Aristeas Epistle 35). It was "the beginning of a wonderful friendship" that resulted in the translation of the Septuagint into King Ptolemy's famous library. King Ptolemy does not end his appeal/request without a promise to send Egyptian dignitaries to Jerusalem who will see to it that many gifts are dedicated to the Jewish Temple "and a hundred pieces of silver for sacrifices and other needs". The Hellenistic Egyptian king immediately recognized the priestly lordship in Judah in order to rule through it, among other things, over the Jewish population.

In response to King Ptolemy's request, Elazar writes a letter with the following words: "Elazar, a great priest, to Ptolemy, the loving, faithful king, peace." May you and Arsinoe, the queen, the sister and the children be healthy... and in the presence of all of them we chose old people, beautiful and good, six for each tribe of Hanum... and these are:... Nehemiah, Joseph, Theodosius... Jason, Jesus, Theodotus, Theophilus... Dostheus... all seventy-two" (Aristeas Epistle 41 and onwards).

From this passage we learn about the intimate relationship between the high priest and the Ptolemaic royal house, which is the result of the above historical circumstances. It also becomes clear to us the degree of Hellenization (Greekness) that began a relatively short time since the beginning of the Hellenistic rule in Judea. This process was encouraged and promoted by the priesthood, for purely pragmatic and even socio-cultural reasons. This matter emerges not only from the use of Greek names, but theophilic names (those that preserve among them the phrase "Theos" - god in Greek) as well as from the phrase "beautiful and good", taken from the Hellenic gymnasium and competitive idealization.

Following on from this passage, it is interesting to present Aristeas' impression of the work of the priests in the temple, one that has a combination of skill, beauty, agility and above all strength, in his words: "And others (priests) raise the sacrifice of the meat and they do it with enormous force. They hold the oxen shanks with both hands, each weighing more than a pair of loaves (we were 21.5 kg X 2) and throw them with both hands at a wonderful speed to a decent height and without missing the spot" (ibid. 92). Whether it is about the exaggeration, both regarding the weight and the practice of throwing, it is certainly interesting how the priesthood demonstrates its physical strength under the influence of Hellenic and Hellenistic culture of course, and from that this phenomenon fits in with the picture drawn above.

In one of the following columns, Aristeas pours out his description of the appearance of the high priest and in the process compares him to the exclusion of royalty. Aristeas is very impressed by the high priest's cassock, by the precious stones on it, by the golden bells around his coat, by the censer on his chest, by his cap and mitt, on which is gold studded and engraved with the name of God.

At this stage, as well as in the following stages, we will search in vain for the Jewish royal line. It faded and disappeared, as if swallowed by the earth. And why is there no response from the people? And at least from the same royal line? Maybe there was and it was not reported, since the writers were usually pro-Hasmonean.

However, an exemption for nothing is impossible, and we note the fact that in 259 BC Zeno, who was the official of the Egyptian Apollonius, visited the area in XNUMX BC and recorded his impressions on papyri. From them it appears that there is no trace of the figure of the high priest, and under him, perhaps, another, oligarchic-aristocratic figure appears in the form of a Trans-Jordanian prince named Tovia, who is a descendant of Tovia the Ammonite of the days of Nehemiah (second half of the fifth century BC). The phenomenon of the rule of the local princes was acceptable to the Ptolemaic house.

And if this is the case, then the Nachshonite rise to prominence of the status of the priesthood in this period, and from that time onwards, shows, it seems, that the quasi-revolution of governance in Judah took place in the days of Ptolemy II Philadelphus of Egypt.

During this period, a mini-revolution takes place in the increasingly institutionalized priesthood. This house sought to perpetuate its position and power and therefore it was determined that upon the death of the high priest the office would pass to his son after him and that his office would be reserved for him for the rest of his life. The "choice"/appointment was therefore independent of any other Jewish factor, except for the high priestly family and certainly the appointment was subject to approval, at least de facto, of the ruling royal house - first the Ptolemaic (until 200/198 BC) and from then on - the Seleucid . The high priest was seen in the eyes of the Ptolemaic government as the "head of the Jews" ("prostatas"), as their official representative and with the authority to collect taxes and duties. The latter position gave the high priest, beyond economic control over the temple and its donations, unprecedented financial power, and one that radiated on the political, social and certainly the personal status.

And if this is the case, that the priesthood functions as a kind of mini-monarchy, there were attempts to rebel against it, not from the direction of the traditional, mythological Jewish royal house, but from another direction - from the house of Tobiah, from the same house of Tobiah. It all started with the kind of rebellion of the high priest Khunio, the son of Shimon the righteous, or simply because of his greed, he did not transfer to the Egyptian king, Ptolemy III, Evergetes, the amount of tax collected from the Jews in the order of twenty pieces of silver. This situation was taken advantage of by Yosef ben Tovia, whose mother was the sister of his son-in-law, to volunteer himself to pay off the debt and to receive a senior status from the Ptolemaic royal family.

Joseph ben Tobiah is appointed by the Ptolemaic house to be the head of taxes and duties in Judea, Phoenicia and Samaria (Samaria), equipped with an Egyptian enforcement force. In this way, the status of the priesthood is eroded and an opening is opened for difficult and oppressive power struggles within the priesthood itself in order to gain power.

The dynasty of the House of Tovia did not become politically powerful and after Yosef ben Tovia steps down from his class stage, he does not leave an heir behind him and the priesthood returns to its former dimensions, but, as mentioned, increasingly fissures begin to form in it between groups seeking power and strength.

In the Jewish Antiquities of Joseph ben Mattathias, there appears a seemingly puzzling text with this language: "And it was also from this name (Shimon ben Hunio - the High Priest) that his son Hunio inherited the position, to whom Arius, king of the Lacedaemonians (sons of Sparta), sent messengers and letters, and this is the text of their writing: 'King of the Lacedaemonians Arius to his peace. We came across one writing (text) and we found that the Jews and the Lacdeimonians are of the same race and are from the house of Abraham... because we are brothers" (Kedmoniot Ha-Jewids 226, 225-XNUMX). No matter how we look at this text, we will find it difficult to accept it as it is: Judah-Sparta; high priest-king of Sparta; A common origin... undoubtedly puzzling.

Well, assuming that the text is reliable, the following hypothesis can be made: Sparta's position at that time was quite inferior. It was anxious, like other cities in Greece, to be placed under the Roman occupation, and therefore it sought allies in the circle of Hellenistic nations, and perhaps the first letter was actually sent from Judah, which was also seeking allies.

In any case, the fact that the correspondence is conducted between the king of Sparta (one of the pair of kings) and the high priest in Judah shows the almost royal power of the latter.

We will conclude the lecture by bringing the testimony of the impression of the well-known writer and poet Shimon Ben Sira who lived and worked during the Hellenistic period in Judea. He devotes many lines to describing the figure, appearance and deeds of the high priest in Judah, many times more than he devotes to the biblical Moses and Aaron, and thus he says among other things: "Great is his brother and the glory of his people - Shimon ben Yochanan the priest, who in his generation was absent from the house and in his days the strength of the temple... in whose days the corner wall of a dormitory was built in the King's Hall. He who cares for his people is happy, and strengthens his city from trouble. What is wonderful about him watching from a tent and coming out of the house of the parochet like a star among the thickets, and like a full moon on the days of the festival and like the sun whistling to the king's palace... around him is a crown of sons..." (The Words of Shimon ben Sira 9:1-XNUMX)

The high priest therefore visually cultivated the temple, strengthened Jerusalem and its walls, took care of its security, conducted the ceremonies in the temple in an impressive manner, took care of the inheritance of his position and status and seemed to be like a king in everything. This is indeed the picture of the situation that emerges regarding the status of the high priesthood in the era of Ptolemaic rule in Judah.

What does the future hold for the senior priesthood? We will deal with this in the following list.

15 תגובות

The article illuminates with data, facts, and of course historical research, one of the lesser-known periods of the Jewish people, which usually remains stuck around one of the impressive achievements (until our time), which were expressed in high values for humanity in Tanach, which also included serious events, such as the murder he committed Menachem ben Hagadi in Terzah, and other serious cases and events that caused the destruction of the First Temple, and later the Second Temple as well.

The background problem when dealing with materials from the period described in the article: the need for precious time that is not available at all, and what remains to be hoped for:

Continue with your unique research work, even if there is no unanimity in all subjects (unanimity is possible only in mathematics), the time of this reaction in relation to the time when the article was published, indicates something in the context of the time dimension.

Dr. Yahyam whistles

fiction stories.

Part III, wonderful!

Thank you!