Antibiotic-resistant bacteria originating in livestock are a deadly risk to humans. But the farmers' lobby in the US prevents scientists from monitoring the risk

- The use of antibiotics is much more common in farms for raising animals for food than among humans. These farms can be the main source of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

- Genes that confer antibiotic resistance are spreading more rapidly and much more widely than scientists first thought; This is shown by recent studies.

- According to industrial agriculture in the US, the concerns are exaggerated, while the researchers claim that the companies in the industry endanger public health.

It was only after one of the pigs rubbed his snout in my butt in a friendly way that I mustered up the courage to touch him. I had seen thousands of his kind in the 18 hours before meeting him, but I preferred to keep my distance. My reserved attitude didn't seem to go down well with this particular pig. I ran my hand over his pink, bristling crown, and in response he let out a snort.

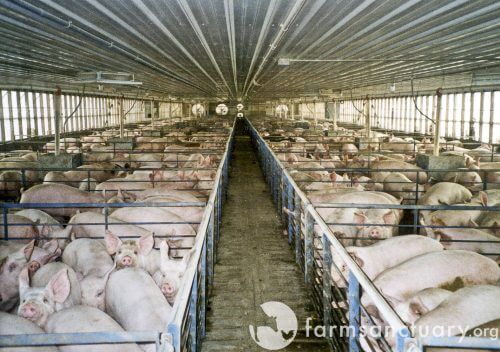

The meeting took place in a crowded and smelly pig sty, on a farm that raises 30,000 pigs each year, in Frankfort, Indiana, a sleepy farming town about 72 miles northwest of Indianapolis. The farm is owned by Mike Bird, who accompanied me on my visit to the place, but the pigs raised there are not owned by him. These belong to TDM Farms, a pig breeding company for the meat industry. Bird signs a contract with the company according to which he raises TDM's pigs from the age of 14 days, from the moment they are weaned from their mother's milk, until the age of six months. When they reach this age, the pigs are transported in trucks to a meat processing plant, which produces pork chops, sausages and fillets from their meat. In the pigsty, which is about 12 meters by 60 meters, about 1,100 pigs are crammed. Since the company pays Bird according to the size of the space he provides, and not according to the number of pigs he raises in it, "it pays for the company to fill the buildings where the pigs are housed to capacity," as Bird explained to me. At half past seven that evening, another shipment of 400 piglets was due to arrive at the farm, on a semi-trailer, and immediately after housing them in their new home, Bird planned to feed them TDM-approved food, food containing antibiotics - a necessary supplement to maintain their health in their crowded housing, whose floor is covered with dung . Antibiotics also help to speed up the growth of farm animals and at the same time, make it possible to reduce the amount of food required to feed them, and for that reason it has long been used as a basic commodity in industrial agriculture.

But the use of antibiotics also has a scary negative aspect, and this was one of the reasons for my reluctance to contact my porcine friend. It turns out that antibiotics turn innocent farm animals into disease factories. Farm animals become a source of deadly bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which is resistant to several main groups of antibiotics and poses a serious problem in hospitals. Although the antibiotics given to live in the breeding farm can be effective in the first stage, some bacteria with antibiotic resistant genes may survive and pass their resistance to a wider group. Recent studies show that segments of DNA that confer antibiotic resistance can be transferred with disturbing ease between different species and strains of bacteria, and this is indeed an extremely worrying discovery. Scientists who followed trucks transporting chickens collected antibiotic-resistant bacteria from the air inside the vehicles they were traveling in. In early 2016, scientists discovered that genes conferring resistance to a certain type of antibiotic that is given as a last resort, after all other antibiotic drugs have failed, spread in the bacterial population in the US and were found in the bacteria in which a woman from Pennsylvania was infected.

Among researchers there is a growing fear - and the recent discoveries only intensify their fears - that the widespread use of antibiotics in agricultural farms is harming our ability to cure bacterial infections. According to scientists, the latest research in this area shows that antibiotic resistance can spread quickly and reach a much wider distribution than previously thought. The study also points to the way in which antibiotic resistance is spread, from the farms to raising animals to our dinner tables. In 2014, the pharmaceutical companies sold about 10,000 tons of antibiotics, which were defined as medically essential, for use on farms to raise animals for food - three times the amount of antibiotics sold that year for human use. In the absence of antibiotic protection, medical problems that are now considered completely routine, such as ear infections, cuts or bronchitis, may turn out to be a death sentence in the future.

However, according to the industrial agriculture lobby, these concerns have been blown out of proportion. The claim that antibiotics "in animals are directly related to the risk to human health is extremely exaggerated, in our opinion," says Richard Carneyvale, the vice president for regulatory, scientific and international affairs bInstitute of Animal Health, a trade group representing companies that manufacture veterinary drugs. According to him and other industry representatives, the studies do not show a direct link between the use of antibiotics on farms and the spread of antibiotic-resistant infections in humans. Moreover, many of the antibiotic-resistant infections common in hospitals today have never been attributed to farms for raising animals for the food industry or for animal meat.

The scientists claim in response that it is the spokesmen of industrial agriculture who exaggerate the scientific uncertainty, and even "manufacture" evidence, in order to protect their interests. "Truthfully, it reminds me of the tobacco industry, the asbestos industry and the oil industry," he says James Johnson, an infectious disease physician who studies antibiotic-resistant pathogens at the University of Minnesota. "We have a long history with industries that harm public health." Johnson and other researchers admit that it is not easy to prove the connection between all the links in the chain, and those involved in industrial agriculture are doing everything they can to make the task even more difficult. Some of the largest companies in the meat industry instruct the owners of farms to keep researchers away from their farms, claiming that for the good of the animals, contact between them and people from outside, who may be carriers of diseases, should be prevented. And so the scientists are denied the possibility to confirm their hypotheses. And as you tell me tara smith, an epidemiologist from Kent State University in Ohio who studies the spread of infectious diseases, the companies "request evidence for each and every step in the chain of infection, but in fact, they tie our hands."

I went to visit Bird's farm and two other farms in an attempt to find out the truth. I decided to follow in the footsteps of the scientists who sought to trace the spread of antibiotic resistance, starting with industrialized livestock and ending with the plate on our dinner table, in order to find out whether pigs, cows, chickens or turkeys raised on antibiotics could indeed wreak havoc on us - or whether innocent animals At the sight of these and the billions of bacteria infesting their bodies, they do not pose any danger to our health.

Pigs are protected

Eighteen hours earlier, I had turned into the driveway leading to the farm Shutmer for raising pigs in Tipton, Indiana. The first thing that greeted me was not the sight of the pigs or the smell of manure, but an ominous yellow sign that announced in huge letters: “Warning: Disease Prevention Program. No Entry!"

Since I was invited to visit the place, I continued driving towards the farm. I parked two cars behind a Ford Taurus, whose license plate bore the words: "Eat Pork." Keith Schutmer, the farm's owner and my tour guide, waved goodbye to me from the front door to my right.

Shutmer explained that he put up the threatening sign as part of his efforts to keep away disease-causing agents and to protect the 22,000 pigs "that he raises every year" from contracting diseases. "It's common to say that it's better to cure the plague before the cure, and this is all the more true on a pig farm," said Shutmer. His receding white hair and broad smile reminded me of John McCain, but there was no mistaking his accent, typical of the Midwesterners of the USA. My host asked me to put on a protective coverall and wrap my shoes in plastic covers before going on the tour to protect the pigs from any bacteria I might carry.

Bacteria are everywhere, but they are most common on food farms, where the animals are literally all covered in feces. (Though I was covered from head to toe in plastic sheeting during every tour of Schottmer's farm, the stench still enveloped me when I returned to my hotel room hours later.) And just as germs are passed from child to child in elementary school, the germs in the animals' feces spread quickly: they They hide under the nails of the visitors who pat the animals on their heads and they contaminate the hands of the farm workers. (In none of the farms I visited did I see anyone wearing gloves.)

In 2005, scientists in the Netherlands, where a large pork industry thrives, found that animal-derived strains of MRSA were causing illness among pig farmers and their families. MRSA bacteria can cause fatal skin, blood and lung infections; They have been common in hospitals for decades and recently people outside the medical system have also been infected with them. In a fifth of all cases of human infection with MRSA, recorded in the Netherlands in 2007, it was found that the infection was caused by bacteria identical to bacteria originating from animals raised on industrialized farms in this country. In view of the findings, the Dutch government announced in 2008 a strict policy designed to reduce the use of antibiotics on farms, and indeed, from 2009 to 2011, there was a 59% decrease in the use of antibiotics in animals in the industrialized livestock farms in the Netherlands. Denmark, which is also one of the largest exporters of pork, banned the use of antibiotics in healthy pigs as early as 1999. In general, the European countries take a stricter line than the one accepted in the USA when it comes to the use of antibiotics in animals.

Today, scientists already know that MRSA bacteria originating from animals raised in industrialized farms are also spreading throughout the United States. When Tara Smith heard about what was happening in the Netherlands, she decided to investigate the issue in the field. And since at the time Smith was engaged in research at the University of Iowa, she turned to one of her colleagues, a veterinarian with connections to some of the farms raising food animals in Iowa, to help her conduct tests to detect MRSA in the pigs raised on these farms. "In the first round of tests, we sampled 270 pigs. "We simply went out into the field and took samples by touching the snouts of many pigs with a cotton swab, not knowing what we were about to discover," says Smith. "70% of the samples were positive for MRSA".

Smith and her colleagues continued their research and published their findings in a series of alarming articles showing the spread of MRSA bacteria in pig farms across the United States. They found MRSA bacteria in the nostrils of 64% of the workers at one of the largest pig farms. On another farm, they discovered MRSA in the food intended for feeding the pigs, even before it was unloaded from the truck that took it to the farm. A little more than 200 meters from another farm, downwind, Smith found MRSA bacteria floating in the air. Other antibiotic-resistant bacteria have been discovered around poultry farms. Researchers from the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University followed chicken trucks in Maryland and Virginia along the peninsula in cars with their windows rolled up. Delmarva. They discovered in the air inside the vehicles, as well as on the cans of soft drinks placed in the cup holder in the car, bacteria Enterococcus Resistant to antibiotics, a type of bacteria that causes 20,000 infections in the US every year.

Moreover, animal dung is used to fertilize agricultural fields, and this means that bacteria swarm en masse in the soil where our food is grown. A 2016 study showed that after fertilizing the soil with manure from pig pens and dairy farms, the relative concentration of antibiotic resistance genes in the soil increased fourfold. In a study conducted in Pennsylvania, it was found that prolonged exposure of humans to agricultural fields fertilized with manure from pig sties, for example people who live near them, increases the risk of developing MRSA infections by more than 30% compared to those whose exposure was minimal. Bird has another business: fertilizing fields with organic manure. Every now and then he loads a tanker with about 25,000 liters of pig manure from his farm and goes to fertilize nearby fields. According to Bird, the entire process is very carefully controlled. First, he must perform soil tests to make sure the fields can absorb the nutrients in the fertilizer. He must also spread the fertilizer at a slow enough rate to prevent it from being washed away. But all these are not enough. An infectious outbreak of Escherichia coli bacteria (E. coli), discovered in spinach crops in 2006, was caused, as it turned out, by the water used to irrigate the fields. The water was polluted with manure from pigs and cows from a nearby farm. The contamination claimed the lives of three people.

Resistance is spreading

Antibiotic resistance is undoubtedly a problem, for humans and farm animals alike. But how can we know for sure that there is indeed a connection between the two and that the problem is getting worse due to the use of antibiotics in livestock? This exact question was asked in 1975 by the Animal Health Institute and to answer it, it recruited the biologist Stuart Levy from Tufts University. Levy and his colleagues gave low doses of an antibiotic drug, Tetracycline, to a group of 150 chickens on a nearby farm, which had never previously received antibiotics as a supplement to their feed. They followed them in order to see what the effect of the antibiotics would be. Within a week, almost all of the Escherichia coli bacteria in the chickens' intestines became resistant to tetracycline. Within three months, the bacteria that multiplied in the chickens' bodies also developed resistance to four other groups of antibiotics. After four months, even the bacteria in the body of chickens that did not receive tetracycline showed resistance to the drug. In a laboratory test of bacteria taken from the bodies of the farm owners, Levy and his colleagues discovered that 36% of them were resistant to tetracycline, compared to only 6% of the bacteria taken from the bodies of their neighbors. The findings amazed the scientists. At that time, "the popular opinion was that it was possible to give antibiotics to animals in low doses without them developing resistance, our research and its findings were therefore unexpected and even more interesting," says Levy. (The Animal Health Institute has since refrained from funding additional studies to confirm Levy's research findings.)

Another study found that 90% of the E. coli bacteria in pigs raised on normal farms are resistant to tetracycline, and an incredibly high rate of 71% of the E. coli bacteria in pigs raised without antibiotics are also resistant to the drug. This is because genes for resistance are spreading and common everywhere. In a groundbreaking study from 2012, the microbiologist Lance Price, who currently heads the Action Center for Antibiotic Resistance Research at the Milken Institute, at the George Washington University School of Public Health, and his colleagues traced the evolutionary origins of MRSA bacteria that were discovered in livestock, pigs and the farmers who raise them, in Europe and the United States. They did this by finding the complete genome sequence of 88 different samples of MRSA bacteria. Their findings show that this strain of MRSA came from humans, where methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus first appeared. From humans, the bacteria moved to farm animals, where they quickly acquired resistance to methicillin and tetracycline and continued to spread.

Antibiotic resistance first spreads slowly, inherited from parent to offspring. The progeny of antibiotic-resistant bacteria therefore have innate antibiotic resistance. But cutting-edge research shows that over time, antibiotic resistance genes find their way into free DNA segments that circle the bacterial genome, and many of them end their journey on circular DNA segments called Plasmids. Copies of plasmids are easily transferred from one species of bacteria to another. In a 2014 study, an international group of scientists collected samples of antibiotic-resistant E. coli bacteria from both humans and chickens. And although the bacteria were genetically different, many of them contained almost identical plasmids, with the same antibiotic resistance genes. And it is these plasmids, whose properties are easily transferred from bacterium to bacterium, and not the bacteria themselves, that spread antibiotic resistance.

The fact that antibiotic resistance can be spread in this way, known by microbiologists as "horizontal" spread, changes the picture completely. This is similar to the situation where doctors suddenly discover that Huntington's disease, which is usually passed down from parent to child, can be transmitted through casual contact between people. It also means that exposure of one type of bacteria to one antibiotic drug, in one place, can affect the response of other bacteria, to other antibiotic drugs and in other places.

But the bacteria pay a price for the antibiotic resistance: usually, the mutations reduce the energy that the bacteria allocate for the purpose of culture. The individual bacteria do survive, but the population of bacteria as a whole grows slowly. And so, when the bacteria are no longer exposed to antibiotics, their antibiotic resistance genes disappear over several generations. However, recent studies show that upon repeated exposure to antibiotics, the bacteria develop genetic mutations that give them resistance and at the same time allow them to continue multiplying at a rapid rate, and in this case, they retain their resistance to antibiotics even after they are no longer exposed to it. "What is really scary is that we have seen that such processes actually take place. Sometimes, plasmids pass from bacterium to bacterium in a patient's intestines and rearrange the genome of the bacteria," says Tim Johnson, a microbiologist at the University of Minnesota School of Veterinary Medicine. "The durability seems to be evolving in real time, and this contributes to amplifying its effectiveness."

Genes conferring resistance to several groups of antibiotic drugs may exist on the same plasmid, so that while one gene gives the bacterium a survival advantage, other genes for resistance "catch a ride" on the plasmid. The extent of the phenomenon, in which two genes pass Choice together, is still unknown; And apparently, there is still the hidden rabbi, "and we are not even aware of it," says Tim Johnson. But knowing these processes is essential for understanding the mechanism of spread and the risks of antibiotic resistance that are involved for us. Some of the antibiotic drugs used in industrialized livestock are rarely used in humans or are not used at all, and the assumption, often voiced by representatives of industrial agriculture, is that the developing resistance to such drugs poses no risk to humans. But the meaning of the phenomenon of the joint selection of several genes together is that the use of a certain antibiotic drug may, in a process in which genes undergo selection together, "give them resistance to another drug," says Scott McEwen, an epidemiologist who studies antibiotic resistance at the University of Guelph School of Veterinary Medicine in Ontario, Canada. The increase in the levels of resistance to antibiotics given to farm animals may also cause an increase in the levels of resistance to penicillin, for example.

What makes matters even worse, as recent studies show, is that when bacteria are exposed to antibiotics, they share their resistant plasmids with each other at a faster rate. It seems as if the bacteria are banding together against a common enemy and sharing their most powerful weapons with their fellow fighters. Once the bacteria become resistant, the presence of antibiotics only increases their resistance. One of the reasons why antibiotic-resistant infections are so common in hospitals is the widespread use of antibiotics in these institutions: the antibiotic drugs eliminate the bacteria that are sensitive to them, but allow the resistant bacteria, which are suddenly left without competitors, to thrive and make it easier for them to transmit infections to medical equipment, medical staff and other patients.

Government counterattack

In view of these alarming findings, one would have expected the US government to act firmly against the use of antibiotics in industrial agriculture. And she does, to a certain extent. In 2012 and 2013, the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published two non-binding recommendations, referred to by it as "guidelines", which were supposed to enter into force gradually by January 2017. According to these guidelines, the companies producing veterinary drugs are asked to update the labels on the drugs Their defined antibiotics are essential from a medical point of view, so that it will be written on them that they should not be given to animals just to speed up their growth, while investing less in their feed. According to the guidelines, the companies are also asked to stop over-the-counter sales of antibiotic drugs intended for animals and to start marketing them only according to a veterinary prescription.

Most of the companies expressed their willingness to act according to the guidelines. The problem is that many livestock owners, including those of Shutmer and Byrd, claim to have stopped using antibiotics as growth promoters a long time ago. According to them, their main purpose in the use of antibiotics today is "disease prevention and control", a use that the new rules do not refer to at all. As long as they receive the consent of their veterinarians for this, these farm owners will be able to continue fattening the animals they raise with antibiotics as a preventive measure in any case where there is concern about their vulnerability to infections. "It seems to me [that this usage] is quite accepted in the industry," says Schottmer, who was crowned in 2015 as the outstanding pig breeder of the year in the USA - a title awarded to him by US National Pork Board, a body established by the US Congress to promote the pig farming industry and is under the supervision of the US Department of Agriculture. Shutmer says that the purpose of the pork council is "to make sure that none of the most common disease-causing agents get a foothold and cause suffering to pigs."

According to the US Department of Agriculture's data updated until 2012, about 70% of pig farms in the US feed the animals huge amounts of antibiotics to prevent or control the spread of diseases; In almost all farms, the pigs receive antibiotics in their feed at some point in their lives. Similarly, more than 70% of cows on beef farms in the US are fed antibiotics that are deemed medically essential, and 20% to 52% of healthy chickens also receive antibiotics at some point during their rearing. But farm owners who sign contracts with large companies cannot even know if and when they are feeding their animals antibiotics, since the companies provide them with feed that has already had antibiotics added to it. When I asked Bird at what age his pigs get antibiotics, he said he didn't know and would have to call TDM to find out.

It makes sense to argue that animals raised in high density on industrial farms need antibiotics; Their growing conditions leave them vulnerable to disease. "In these overcrowded conditions, it is even more difficult to fight pathogens, and the risk of infections increases," he says Steve Dritz, a veterinarian at Kansas State University. “The pigs I saw in the farms I visited crawled or lay huddled on top of each other; Some of them dozed off inside their horse or sniffed around it." In recent decades, there has been a dizzying increase in the number of animals on industrialized farms in the USA to the point of a "population explosion": in 1992, only 30% of livestock farms raised more than 2,000 pigs in each round of breeding, and by 2009 their share had risen to 86% of all pig farms In the USA, and this, to a large extent, since many of the small farm owners have closed their businesses. The owners of these farms are under heavy financial pressure. Pork prices in the market are falling. Companies that sign contracts with chicken coop owners oblige them to regularly upgrade, at their expense, their already expensive equipment. In 2014, only 56% of medium-sized farm owners reported any actual income from their businesses.

Under these conditions, "perfect management and a perfect working environment - and perfect conditions in every sense - are mandatory requirements for disease prevention on any farm. And in their absence, ranchers are likely to lose their herds," says Tim Johnson. "This is not the fault of the farm owners, but of the industry that pushed them to this."

Links in the sausage chain

The morning after my day of touring Schottmer's farm, before I set off for Byrd's farm, I went down to sample the breakfast buffet at the hotel where I was staying. I stopped for a moment by the sausage stand: did they come, at least in part, from Shutmer's farm? He sells most of the pigs he raises to the corporation Indiana Packers, and the company processes their meat and markets it to local retailers. It is quite possible that the meatballs placed before me are made from animals raised on his farm.

I took one meatball, reluctantly. I asked myself what are the chances that the meat will cause me an infection resistant to antibiotics? When farm animals are slaughtered, the bacteria in their intestines can contaminate their meat. In a 2012 study, Food and Drug Administration scientists tested cuts of raw meat sold to retailers across the US and found that 84% of chicken breast cuts, 82% of ground turkey, 69% of ground beef and 44% of pork ribs tested were contaminated with bacteria. Islets originating from the intestines of animals. More than half of the bacteria found in the ground turkey meat were resistant to at least three classes of antibiotics. These bacteria can cause food poisoning when the meat is not cooked properly, or when the person handling the raw meat does not wash their hands after touching the meat.

But recent studies show that pathogens found in the food we eat may make us sick in other ways as well. Price and his colleagues are engaged in researching strains of coliforms that Price calls COPs [the acronym for colonizing opportunistic pathogens]. As he explains in an article published in 2013, these bacteria find their way into the human body through food, for the most part, but in the first stage they do not cause disease; They simply settle in the intestines and join the billions of "good" bacteria that inhabit them. At a later stage, these E. coli colonies can cause infections in other body organs, such as the urinary tract, and cause serious diseases. The article mentions that urinary tract infections among women at the University of California at Berkeley that occurred in 1999 and 2000 were caused by identical strains of E. coli that apparently came from contaminated food that the women ate.

The American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were only able to identify the causes of contamination in about half of the large-scale food poisonings that have occurred in recent years in the United States. However, the causes of infections that develop gradually are much more difficult to detect. Even if the hot dog I ate that morning was contaminated with antibiotic-resistant COPs, I will never know for sure if I actually ate an infected hot dog. And if months later it became clear to me that I was suffering from a serious infectious disease, I would not be able to prove that the cause of the disease was the meal I ate that morning. And I probably wouldn't even remember that breakfast.

And this is the root of the problem: tracking the course of development of infections resistant to antibiotic treatment and locating the primary causes of the bacterial infection is difficult, if not impossible. "It's a long way - in geographical terms, in terms of time and in other ways - from the farm to the plate," says McEwen. A hamburger can be made from the meat of 100 different cows, so it is impossible, in fact, to order the one particular cow that was infected. And the scientists are required not only for this impossible task, they must also find out whether the way the animals were raised - whether or not they received antibiotics, and if so, for how long, in what dose and for what purpose - affected the bacteria infesting their bodies and ultimately caused the outbreak of the disease infectious or aggravated. Bacteria originating from livestock pose a direct risk only to farm workers and residents living nearby, but not to the general public, according to industrialized agriculture. This is the reason why scientists try to go to farms for raising animals for food, to stand for the nature of the bacteria in these farms and to find what they have in common with the disease-causing agents in the population as a whole.

However, this type of information is almost never available. "Very little data is collected at the farm level," admits Bill Flynn, deputy director for science policy at the FDA's Center for Veterinary Medicine. In September 2015, a meeting was held between the representatives of the Food and Drug Administration, the Ministry of Agriculture and the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control, where the three bodies formulated a plan to collect data in the field, but they did not receive the necessary funding to implement the plan. As of fiscal year 2016, the FDA has not received a single dollar of the $7.1 million it requested to research antibiotic resistance in animals.

Academic researchers also want to investigate the issue in the field, in animal farms, but they rarely get access to them, unless they have personal connections. When Smith asked to collect samples from industrialized turkey farms, she called each of the farms listed as turkey farmers in Iowa. "None of the farm owners allowed us to visit the place," she says. Price and his colleagues had to buy pig snouts from butchers in North Carolina and took bacterial samples from them by eating the snouts, as they did not have access to the live pigs. And do you remember the researchers from Johns Hopkins University who followed chicken trucks in their cars? They had to conduct the research in this way because they had no other possibility to get close to the chickens - they were not allowed to visit the farms.

The ranchers have nothing against science; Their employers, the meat companies, are to blame for keeping foreigners away from the farms. A huge majority of the owners of poultry farms in the USA, between 90% and 95% of them, and about half (48%) of the owners of pig farms (including Bird), sign contracts for raising the animals with large companies in the meat industry such as Tyson Foods,Smithfield Foods וPurdue Farms. The owners of the farms are, in fact, enslaved to these companies, as they borrow huge sums of money to launch their businesses, since the cost of setting up a poultry farm or pig farm is about a million dollars, but they have no chance of reaching profitability without a contractual commitment to these companies. Often, the farm owners have no choice at all because only one company operates in their area.

These contracts with the companies in the meat industry - such a contract, which was signed not long ago, came into the hands of Scientific American from a farm owner who previously worked for Pilgrim's Pride, the largest company in the US for processing and marketing chicken meat - include sections dealing with the protection of animals, including explicit instructions for farm owners to "restrict the movement of non-essential people, vehicles and equipment" around the farms. My visit to Byrd and Schottmer's farm is coordinated and pre-approved by the Pork Board. But when a poultry farmer named Mike Weaver invited a journalist to visit his farm a few years ago and this was revealed to his employer, "I was forced to attend a 'refresher course on biological safety' and delayed for two weeks a new shipment of poultry that I was supposed to receive, which caused me a loss of income of about 5,000 dollar," says Weaver. Price, in his capacity as a scientist, managed to convince a handful of ranchers years ago to allow him access to their farms, but then, says Price, "they lost their contracts."

Despite repeated requests, Farm Office, the U.S. industrial agriculture trade group, and Smithfield Foods, the world's largest pork processing and marketing company, declined to comment for this article or answer the question of whether industrial agriculture companies are working to keep scientists away from farms.

Whatever the reasons, the lack of data allows the industry to oppose regulations and thwart legislative initiatives. In 1977, immediately after Levy's research was published, the FDA announced that it was considering banning the use of some antibiotic drugs as an additive to animal feed, due to concerns about the safety of their use. During the 39 years since then, the industry has fought with all its might against these programs, claiming that there is no conclusive proof that the drugs are harmful. In view of the public relations campaign conducted by the industry, the FDA finally changed its tactics, says Flynn, and instead of binding regulations, the administration is now content with publishing non-binding guidelines.

But according to many in the field, since the guidelines allow the continued use of antibiotic drugs for disease control, these guidelines are largely worthless. "Will there be a decrease in the scope of antibiotic use? I believe there is no chance of that," he says H. Morgan Scott, a veterinary epidemiologist at Texas A&M University. In fact, since the guidelines were published for the first time, there has been a constant increase in the annual sales volume of antibiotic drugs to farms for raising animals. organization Pew In 2014, the American, which operates as a non-profit, conducted a review of the drug labels of all 287 antibiotic drugs to which the guidelines are supposed to apply, and found that the farmers could still continue the use of a quarter of them, at the doses in which the drugs had been given until then and without limiting the duration of treatment, as long as they They will declare that the use of medicines is intended for the prevention or control of diseases. Even Carneyvale of the Animal Health Institute says that the FDA's guidelines "could have changed the situation in terms of how [antibiotics] are used, but we still have to wait and see if they will actually affect the total amount of antibiotic drugs in use."

The requirement for a veterinary prescription for the marketing of antibiotic drugs intended for animals is also not expected to affect, even slightly, the scope of antibiotic use in the industry. Many of the veterinarians give prescriptions for antibiotic drugs and even sell them as part of their business activities, as an additional source of income, and many of them also cooperate with the food industry or the pharmaceutical industry. A press investigation by the Reuters news agency from 2014 revealed that half of the veterinarians who advised the FDA on the use of antibiotics in animal feed in recent years received funds from pharmaceutical companies. "Many veterinarians maintain close ties with the industry, are in conflict of interest and are committed to the big manufacturers - so they tend to preserve the status quo," says James Johnson.

Several members of the American Congress, including the representative of the state of New York in the House of Representatives, the microbiologist Louise Slaughter, filed bills calling for stricter controls on the use of antibiotics on farms. For more than a decade, Slaughter has been trying to advance its legislative initiative designed to ban the non-medical use of antibiotics, which are defined as medically essential, on farms for raising animals for food. Its legislative initiative is supported by 454 organizations, including American Medical Association. But since the bill was transferred to the subcommittee on health of the Energy and Commerce Committee of the House of Representatives, the issue has not been put to a vote.

One of the members of the committee, who at this stage does not support the bill, is a representative of Pennsylvania in the House of Representatives Tim Murphy, has publicly and officially warned against the continued use of low-dose antibiotics in food animals and the dangers that antibiotic-resistant bacteria pose to our food supply, as his spokeswoman Carly Atchison reports. But he does not believe, according to Atchison, that the bill "reflects the balance required in the use of antibiotics defined as medically essential in agriculture and farms," the law also met with strong opposition from the industry. American Poultry Council, a trade association that represents companies engaged in raising poultry for food and processing and marketing chicken meat, invested $640,000 in lobbying activity in 2015, among other things, in an effort to thwart legislative initiatives on the use of antibiotics, and the Animal Health Institute invested $130,000 in such activity, as reports show Center for Responsive Policy, the American non-profit research group. The center's data also shows that companies producing veterinary drugs and companies engaged in raising animals for food made donations of more than $15,000 to the election campaigns of more than half of the members of the subcommittee for health. "The trade organizations that pulled the strings behind the scenes argued in their defense: 'You can't prove that we are the ones who provoked the resistance,'" says Patty Labre, deputy director of The Food and Water Guard, a non-profit organization operating from the American capital, Washington. "That's what really put a stick in the wheels."

A small scale solution

After saying goodbye to Bird, I set off for my last destination on the farm tour, a two-hour drive away: a farm Seven Sons ("The Seven Sons") in Roanoke, Indiana, which raises pigs in pastures and wooded areas, without antibiotics. Until a decade ago, this farm was no different from the two farms I visited earlier: it raised 2,300 pigs a year for Tyson Foods and used antibiotics regularly. But the members of the family that ran the farm were worried about the effect of antibiotics on health and decided to change direction. In 2000, the farm became a renewable mixed farm, as the owners of the farm call it. Today, 2000 pigs, 400 laying hens and 2,500 cattle are raised there, on pastures that cover more than 120 dunams.

Blaine Hitzfield, the second of the seven Hitzfield sons after whom the farm is named, took me on a short tour of the place. I saw less than a dozen pigs lounging to their pleasure on an area of grass and soil that was about two acres in size. Hitzfield did not ask me to wear overalls, and the fact that I had only recently visited another pig farm did not cause him any concern. The animals on his farm, Hitzfield explained, are more vaccinated than those raised in closed and crowded pens: the animals raised on the farm not only enjoy open spaces and freedom of movement, they are also weaned at a later stage, so they develop a stronger immune system. Nature also contributes its part: the sun is an excellent disinfectant, and the mud works wonders in keeping parasites away," says Hitzfield. (And if a particular pig does contract the disease, it is treated with antibiotics at the farm, but then sold at auction rather than under the Seven Sons Farm brand name.) Hitzfield's words are backed up by scientific research. In a 2007 study, researchers from Texas Tech University reported that pigs raised in open spaces had increased activity of immune cells that fight bacteria, cells called Neutrophils, an activity much more vigorous than that found in animals raised in closed buildings.

Hitchfield admits that Seven Sons Farm's approach to animal husbandry is unlikely to be adopted as the vision of industrial agriculture. "Farmers with an accepted attitude will say, 'This is absurd; It will never work; Such a farm cannot develop and expand - and in a way, they are right," he says. Seven Sons Farm is a small scale prototype, but Hitzfield believes that over time, and following further research, larger farms of the same type will certainly be possible. "In terms of output per hectare, we are more productive today than we have ever been," Hitchfield said.

Some industrialized animal interfaces are already undergoing change, and this is in no small part thanks to consumer demand. Admittedly, they do not become small mixed farms, but the change in perception gives its signals. In February 2016, Purdue announced that two-thirds of its poultry would be raised without medically important antibiotics. Tyson Foods has pledged to stop using antibiotics intended for humans by September 2017 to raise its chickens on farms in the US. Industrial breeding of broiler chickens without the use of antibiotics is much easier than raising pigs, cows or turkeys, because broiler chickens leave the farm for slaughter at a younger age.

Consumer demand is also spurring some of the major producers of pork to reduce the use of antibiotics. "This is not an easy task to accomplish," says Bart Vettori, vice president and general manager of the beef division of Purdue's food division, within which the natural food manufacturer operates. Coleman Natural Foods. The Coleman company raises pigs on a vegetarian diet free of antibiotics. "There is demand in the market. Our consumers are more understanding than they were in the past, they are more informed than ever and they are asking more questions than they have ever asked," says Vittori. also online Nieman Ranch, which has more than 725 family farms for raising pigs, lambs, cows and laying hens operating throughout the US, the animals are raised without antibiotics.

Coleman's products and products from niche farms, such as Seven Sons Farms and the farms affiliated with the Nieman Ranch chain, are currently too expensive for many Americans. But as the consumer demand for antibiotic-free meat increases, so will the supply, and if we rely on the laws of economics, then at the same time, its price in the market will decrease.

Scientists are still grappling with the issue of antibiotic resistance, and many questions remain unanswered: questions that will be impossible to answer as long as food manufacturers keep aliens out of their farms. But even so, the evidence accumulated so far clearly points to the need to reduce the use of antibiotics in farms for raising animals for food. As an alternative, science currently offers an innovative treatment regime for infection control, and even recognized traditional methods, such as raising animals in open spaces. Until these methods are implemented, at least in part, the alarming increase in the spread and resistance of the bacteria swarming in our food and the powerlessness of medicine in the war against them will continue to trouble all of us - researchers and ordinary people alike.

good to know

Antibiotic resistance: this is how superbugs are created

Antibiotics were developed to kill bacteria or stop their spread. But in doing so, the antibiotic drugs cause changes in the bacterial populations and reshape them. They create conditions that give a survival advantage to bacteria that have genes that help them fight drugs. These genes are inherited in a process known as vertical transmission, ensuring the survival of a high percentage of the bacteria in future generations. An even more serious danger involves a process known as horizontal transfer, in which antibiotic-resistant genes "jump" from one strain or species of bacteria to another and thus spread rapidly and are widespread everywhere. When such bacteria cause infectious diseases in humans, they neutralize the effect of the antibiotic drugs given to patients and leave them without protection.

About the writers

for further reading

- Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Pigs and Farm Workers on Conventional and Antibiotic-Free Swine Farms in the USA. Tara C. Smith et al. in PLOS ONE, Vol. 8, no. 5, Article No. e63704; May 7, 2013

- Prevalence of Antibiotic-Resistant E. coli in Retail Chicken: Comparing Conventional, Organic, Kosher, and Raised without Antibiotics. Version 2. Jack M. Millman et al. in F1000 Research, Vol. 2, Article No. 155. Published online September 2, 2013

- Multidrug-Resistant and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Hog Slaughter and Processing Plant Workers and Their Community in North Carolina (USA). Ricardo Castillo Neyra et al. in Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 122, no. 5, pages 471–477; May 2014

- Livestock-Associated Staphylococcus aureus: The United States Experience. Tara C. Smith in PLOS Pathogens, Vol. 11, no. 2, Article No. e1004564; February 5, 2015

- Detection of Airborne Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Inside and Downwind of a Swine Building, and in Animal Feed: Potential Occupational, Animal Health, and Environmental Implications. Dwight D. Ferguson et al. in Journal of Agromedicine, Vol. 21, no. 2, pages 149–153; 2016

- The enemy among us, Marin McKenna, Scientific American Israel, July 2011

- Chicken pellets: just say no! Kivi Nachman, Scientific American Israel, July 2011

2 תגובות

Cheryl to start working towards a transition to a vegetarian world.

I remember learning about it in a microbiology course more than 20 years ago.

I remember a completely distinct graph where you see the increase in the use of antibiotics of various types in agriculture against the development of resistance of bacteria against those antibiotics.

The issue of transferring genes between bacteria (conjugation) has been known for a long time - since antibiotics are a product that is produced in advance by bacteria (and fungi), there will always be a bacterium that has resistance to the antibiotic, and thus in a meeting of bacteria, a bacterium transfers the gene that confers resistance to another bacterium through conjugation And then, in an environment rich in antibiotics, a process of natural selection takes place... and a resistant strain develops in large quantities.

In the event that this bacterium is also a pathogenic bacterium - we have a problem.

In the stomach of the cow and other ruminants (fermenting stomach) there is the most efficient laboratory where bacteria of all kinds meet with each other and with antibiotics that the cows receive in their food in huge quantities.

It is also known that the authorities at the time (about 20 years ago) made a decision to keep some types of antibiotics and not allow farmers to use them.