The findings were discovered thanks to the development of advanced technology that allows scientists to activate - wirelessly - target cells in the brains of mice that are in a highly stimulating environment

After two months of family confinement under the auspices of the Corona epidemic, some couples have come out closer and more loving than ever - while others are groping their way to the steps of the rabbinate. Also the hormone oxytocin, a neuromodulator that has earned the nickname "the love hormone", does not necessarily bring hearts together, but may promote anxious and even aggressive behaviors. This conclusion emerges from a unique study in mice that for the first time combines the activation of advanced genetic tools that enable specific nerve cells in the brain to be activated in a controlled manner and over time, and monitoring the mice in an environment that simulates their natural living conditions. the findings, published today in the scientific journal neuron, may shed new light on the therapeutic potential of oxytocin in a variety of psychiatric conditions - from social anxiety and autism to schizophrenia.

It is now known that the behavior of animals under controlled laboratory conditions does not necessarily reflect their behavior in the wild, especially as far as social behavior is concerned. Despite this fact, most of the scientific knowledge in the field of brain research is based on experiments with model animals in a sterile and low-stimulus environment, which makes it possible to isolate variables and reveal neural mechanisms. But if behavior in the laboratory does not reflect natural behavior, to what extent can these studies be extrapolated to the complex human reality?

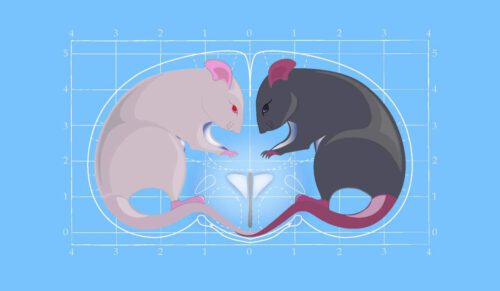

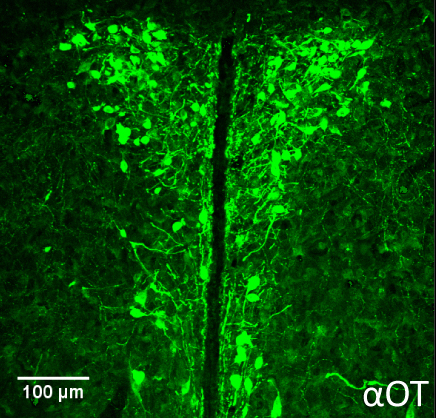

To answer this, developed in the past in the research group of Prof. Alon Chen The neurobiology department has a unique approach that allows mice to be observed in the laboratory in a highly stimulating environment that mimics their natural living conditions; Their extensive social activity is recorded using video cameras and analyzed by computer. In the current study, which lasted about eight years, the scientists, led by research students Sergey Anfilov and Noa Aran and staff scientist Dr. Yair Shemesh from Prof. Chen's group, presented a significant leap forward in this approach: into the environment that simulates natural living conditions, they introduced one of the biggest revolutions in research The brain in recent years: optogenetics - the ability to "turn on" and "turn off" specific cells in the brain through light stimulation. The researchers were able to do this by developing a compact and lightweight wireless device that allows a group of mice to run freely in a rich and challenging environment, while the scientists remotely activate target cells in their brains and control each mouse individually. "The goal was to find the research golden path," says Anfilov. "To trace behavior in a quasi-natural environment without giving up the ability to ask scientific questions concerning neural mechanisms".

"Besides the paucity of stimuli, in most classical behavioral tests in the laboratory the response is measured for a few minutes, while our system makes it possible to follow social dynamics over days," adds Dr. Shemesh. To this end, the researchers used a unique protein developed by Prof. Ofer Yizhar, also from the Department of Neurobiology, who was a partner in the research; This protein allows not only to "turn on" or "turn off" specific cells, but also to make them more sensitive over time.

For the first "test drive" of the system, the researchers chose a controversial question: what is the role of the hormone oxytocin? Over the years, the prevailing view was that this neuromodulator increases sociable behavior. However, in recent years, evidence has been growing that oxytocin may also promote completely different behaviors. In order to deal with the contradictory findings, the "social salience" hypothesis was put forward in recent years, according to which oxytocin does not necessarily encourage sociable behavior but rather serves as an amplifier for the reception of social signals - the interpretation of these signals and the accompanying behavioral response depend on a complex social context.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers moderately and over time activated the oxytocin-producing cells in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) in the hypothalamus of mice in an environment simulating natural living conditions - as well as in a complementary experiment of mice in a sterile environment according to the protocol of a classic behavioral test. The researchers saw that the mice in the quasi-natural environment first showed increased social curiosity, but this was later accompanied by an increase in aggression, while in the classical behavioral test - the activation of the oxytocin cells actually reduced aggression. "In the enriched environment, we observed a group of males living together in the same arena and competing for resources such as territory and food. It is possible that due to the atmosphere of competition, the social interest was gradually replaced by aggression. In other words and in light of the findings in the classic test, it seems that the social context is what determined how the oxytocin will affect", says Anfilov.

In light of the new findings, it is possible that instead of the "love hormone", a more appropriate name for oxytocin is the "social hormone". "Scientists used to think: 'Oxytocin increases eye contact and brings people closer together - maybe it can be used as a medicine.' Many studies have even examined the possibility of treating autism and social anxiety using oxytocin, but the findings are not consistent," says Arane. "Our work confirms the hypothesis that oxytocin does not increase sociability in an overwhelming way - but its effect depends on the context and nature." The researchers emphasize that the findings do not invalidate the future therapeutic potential of oxytocin: "The purpose of the study is to present the complexity of its effect and to emphasize that if we want to understand complex social behaviors, there is a need for studies in a complex environment - only then will it be possible to translate the findings to humans as well."

In the study, which was conducted in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry in Munich, the research students Assaf Binyamin and Stoyo Karmihalev, the staff scientist Dr. Julian Dean and the post-doctoral researcher Oren Furkosh from the laboratory of Prof. Chen, the electronics engineer Avi Dagan as well as Prof. Shlomo Wagner and the researcher also participated Post-doctoral fellow Ella Haroni-Nicolas from the University of Haifa and Prof. Inga Neumann and research student Vinicius Oliveira from the University of Regensburg in Germany.

More of the topic in Hayadan:

One response

To somewhat correct the sullen impression of some of my comments, I would like to praise this article. It is excellently written, with a factual description of important and interesting research without getting carried away by unfounded claims.

Align power.