Aharon Chechanover and Avraham Hershko from the Technion in Haifa, and the American Irwin Rose, won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 2004, due to their work on how the human body produces proteins to protect itself from infections * We will try to expand later in the holiday

Two Israelis, Aharon Chechanover and Avraham Hershko from the Technion in Haifa, and the American Irwin Rose from the University of California, are the winners of the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, as reported by the prize committee in Stockholm, Sweden.

They won the award for their work on how the human body produces proteins to protect itself from infections. In doing so, they join the winners of the Nobel prizes in medicine and chemistry announced in recent days.

The page about Prof. Chachanover on the Israel Awards website. Won the award in XNUMX

Discovered ubiquitin

The three actually discovered in the late XNUMXs and early XNUMXs the ubiquitin system, which is responsible for breaking down proteins inside the cell, and controls many biological processes such as cell division, DNA repair and the quality of new protein production, as well as essential parts of the immune system.

The award committee wrote in its decision: "When the system does not work properly we become sick: cervical cancer and cystic fibrosis are two examples of this. The work of the three helped to develop drugs that can deal with these conditions." The three will share a prize worth 1.6 million dollars.

The Minister of Science and Technology, Ilan Shelgi, hastened to send his congratulations: "Winning the prize is a great honor for you, the Technion and the State of Israel. Israeli science is appreciated and recognized internationally and now Israeli scientists have joined the distinguished list of Nobel Prize winners in the exact sciences."

The body is in the process of destruction and reconstruction

Professor Aharon Chachanover writes about his research: "It turns out that the human body and organisms in general - unlike the metal body of the car or the stone walls of the house in which we live - are not static, and are in a constant process of destruction and reconstruction, to the extent that every day we replace -10% of the total body components. The proteins that make up the body's muscles and bones and are also catalysts and controllers for all the chemical reactions that take place in the body are no exception, and they also change."

Chechenover adds: "The main question asked: why are we required for such an intense dynamic of destruction and construction, and what is the mechanism that implements it. The demand for dynamics arises for two reasons: one, because the proteins have an extremely complex structure and their function is sensitive to structural changes that occur as a result of genetic changes, the effect of the temperature we live in, radiation and environmental pollutants. The body must eliminate the damaged proteins, produce new ones under them, and at the same time leave the undamaged ones."

the badge of death

The second reason according to the study is "the control of certain procedures requires the elimination of specific proteins that are used as brakes or catalysts for these procedures. The basic mechanism that removes the proteins was discovered during the research I carried out as a research student under the guidance of Prof. Hershko. Proteins destined for destruction are first marked by a 'death tag', which is a protein called ubiquitin. Only those marked will be destroyed. Disturbances in the functioning of the system for eliminating damaged proteins have been found, among other things, to be the basis of many malignancies and degenerative diseases of the brain."

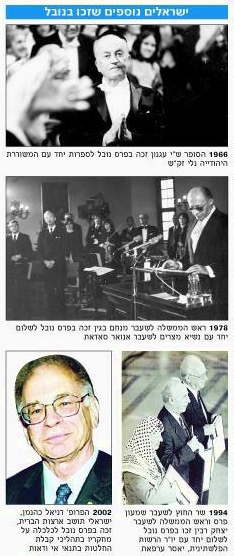

To date, besides Chechanover and Hershko, five other Israelis have won the prize: the writer Shay Agnon (1966, Nobel Prize for Literature), the late former Prime Minister Menachem Begin (Nobel Peace Prize, 1978), Shimon Peres and the late Yitzhak Rabin (Nobel Peace Prize, 1994) and Daniel Kahneman (Economics, 2002).

A tradition of more than a century

The Nobel Prize is awarded annually to selected individuals for their contributions to science, literature and humanity as a whole. The prize was founded by the Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, who bequeathed his assets to the foundation that bears his name and is responsible for distributing the prizes. Nobel died in 1896, and the first prizes were awarded in 1901.

Originally, the award was given in five fields: physics, chemistry, medicine and physiology, literature, and peace. In 1968, the Nobel Prize in Economics was also added, from the Bank of Sweden's donation in Nobel's memory, and was awarded for the first time in 1969. In his will, Nobel emphasized the importance of awarding the prize to scientists and creators, as well as to individuals who contributed in their work to the well-being of the human race and its advancement.

Every year, the award committees turn to a large number of experts (about 1,000 in each field, including past laureates), requesting to receive proposals for candidates for the award. Each committee usually receives 100 to 200 names, and closes the list of candidates on January 31 of the year of the award.

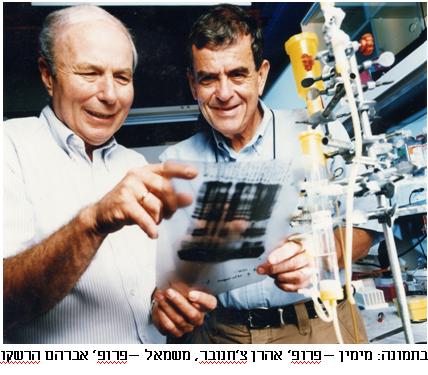

Professors Avraham Hershko and Aharon Chachanover from the Technion - Nobel Prize winners in chemistry

Technion spokesman's announcement, October 6, 2004

Research Professor Avraham Hershko and Research Professor Aharon Chachanover of the Technion are the winners of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 2004. They won the prestigious prize together with Professor Irwin Ross from the University of California at Irvine.

Professors Hershko and Chachanover, from the Ruth and Baruch Rappaport Faculty of Medicine at the Technion, are the first researchers to describe the ubiquitin system, which is responsible for breaking down proteins inside the cell, and thereby led to a breakthrough in cancer research, degenerative brain diseases and many other diseases. Their discovery fundamentally changed the scientific understanding of intracellular processes.

The president of the Technion, Professor Yitzhak Afluig, expressed great pride and satisfaction on behalf of the entire Technion House for the historical achievement of the Technion scientists. "This is a certificate of honor for Israeli science in general and the Technion in particular," he said.

Research Professor Aharon Chachanover was a student of Prof. Hershko and together they managed to reach the breakthrough that earned them the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Both are winners of the Israel Prize.

Chechenov Nobel winner: damage to higher education - suicide

By David Ratner and the "Haaretz" service

Prof. Aharon Chechanover and Prof. Avraham Hershko from the Technion and the American Irwin Rose won the prize for their work in researching the breakdown of proteins in the cell. A prize of 1.3 million dollars will be distributed; So far 5 Israelis have won the award.

The Israelis, Prof. Aharon Chachanover and Prof. Avraham Hershko of the Technion, and the American Irwin Rose won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for their work from 1980, which revealed one of the most important cyclic processes in the cell that enables the breakdown of proteins. This was announced yesterday (Wednesday) by the award committee in the capital of Sweden, Stockholm. Chechenover, 57, Hershko, 67, and Irwin Rose, 78, will share the $1.3 million prize between them.

"Thanks to the work of the three researchers, it is possible to understand at a molecular level how the cell controls several key processes, by breaking certain proteins and not others," the academy wrote in its decision. "An example of such processes are cell division, DNA repair, quality control and new production of proteins and important parts of the immune defense system."

Chahanover is the director of the Rapaport Research Center at the Technion in Haifa. Hershko works at the center as a professor. Both Israelis have previously won the Israel Prize in Biology Research: Professor Hershko won the prize in XNUMX and Professor Chakhanover won in XNUMX.

In an impromptu press conference at Hershko's house, the two sent a stern warning about the state of the education system. "The State of Israel will always be short on resources and we need to focus on things that are important, innovative, that can be a breakthrough," said Prof. Hershko. "We won't be able to do that when the education system is collapsing."

Prof. Chachanover was more firm: "Higher education in the State of Israel is in a difficult situation. The Technion is suffering greatly, suffocated by budget strangulation. I returned four days ago from a sabbatical in the US, and I'm jealous of what they can do. It is possible to make do with slightly less budgets, but not much less."

"An event like this, which Israelis win, is rare. We have no oil, uranium or diamonds. Israel depends on higher education. Everything we have - the IDF, Rafael, a sophisticated industry depends on what we have in mind. Going to chop off this head is an act of suicide." Chechenover emphasized that the research for which he and Rashko won the Nobel began 35 years ago, and the scientific achievement was achieved a decade later. "It takes years to train scientists for achievements. The schedule for scientists is not as short as for politicians. Harming scientists today will cost us dearly in the future."

The third winner, Rose, is an intern in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics at the University of California College of Medicine. Yesterday, Professor David Gross, a graduate of the Hebrew University, was announced as one of the winners of the Nobel Prize in Physics. Together with him, Prof. David Pulitzer from the Physics Department at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena and Prof. Frank Wilchek from the Physics Department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) won the award.

Two Israeli scientists from the Technion won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

By Tamara Traubman, David Ratner and Ruthi Sinai. Haaretz, 8/10/2004

Avraham Hershko and Aharon Chachanover won for their research on protein breakdown

Two biochemistry professors from the Technion in Haifa, Avraham Hershko and Aharon Chachanover, won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 2004 on Wednesday. This is the first time that Israeli scientists have won the Nobel Prize. The award committee, in Stockholm, Sweden, announced that the two won, together with an American researcher - Professor Irwin Rose from the University of California - thanks to their research on the breakdown of proteins in the human body. The value of this year's prize is 1.3 million dollars and it will be divided equally between the three winners. The award ceremony will take place on December 10 in Stockholm.

The collaboration between Hershko and Chechanover began in the late 70s, when Chechanover did his doctoral thesis in Hershko's lab at the Technion. Together they discovered the "death tag" of proteins, a molecule that sticks to damaged proteins or those whose time has come to die, and signals to the cell that it must be broken down (see below).

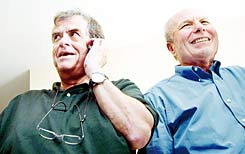

One can assume that in a slightly more reformed country, Hershko and Chechenover would have found themselves embalmed in suits in a prestigious hall, answering the journalists' questions a few hours after the announcement that they had won the Nobel Prize. But in Israel things are conducted differently.

On Wednesday morning, Hershko's family members were busy searching for him. Hershko was not at his home in Carmel, nor did he answer his cell phone, as usual.

Finally, after more than an hour of searching, one of the aunts found him in the swimming pool in a kibbutz near Haifa, along with his wife and granddaughters. A short time later, the phone at his home stopped ringing and the house began to be filled with bouquets of flowers.

At three o'clock in the afternoon, a car arrived at the family cottage of the Hershko family, and a man in his fifties, dressed in jeans and a t-shirt, got out of it and hopped up to the second floor. The photographers did not notice the shy entrance of Prof. Chakhanover - Hershko's partner in the award, until the two stood with an embarrassed smile for a joint photo in the family living room. One of the Technion officials muttered an apology for the fact that the impromptu press conference was not held in one of the halls of the institution's magnificent buildings: "The rabbi of the Technion would have caused us problems on a holiday," he said.

When the living room became crowded, the entourage moved to the balcony. The phones didn't stop ringing with congratulatory calls. Judith Hershko, who immigrated from Switzerland 40 years ago and married Avraham, said that the first call in the morning came from the Prime Minister of Hungary, Frans Giorszny, who wanted to congratulate her husband who was born there 64 years ago. "If you swam 100 meters in the pool, even the Minister of Education would congratulate you," scolded Professor Hershko, one of the family's relatives.

Rekha Chahanover, Aharon's wife, said that the phone at her house was picked up in the morning by the son Tchai, who heard on the other end a polite man with a Swedish accent asking for his parents. "The first thing I ran was to get water," says Remocha.

The two professors turned out to be relaxed people with a lot of patience for the reporters' demand to "explain in one sentence the scientific achievement you worked on for 35 years". Only Chechenover occasionally glanced at his watch, worried that he was going to miss the daily evening walk on the south coast with his regular friends.

Several interesting facts emerged from the press conference. First, it is impossible to explain in "one sentence" the enormous scientific achievement of the two; Second, they haven't patented it, so they won't be billionaires anytime soon; Thirdly, both of them had hoped that one day they would receive a Nobel Prize in Medicine, so they were really surprised by the prize in Chemistry.

Chechenover said that the factors that contributed to the achievements that won him the award are diligence (his work day starts in the early morning and can last up to 12 hours), the right mindset and luck. Hershko attributed his achievements to his determination, which continued to research the field of protein breakdown, "even when it was unpopular and everyone went in the other direction - the study of protein formation."

During the holiday, many Israeli scientists grumbled that the Prime Minister of Israel, Ariel Sharon, had not yet called to congratulate. The Minister of Education, Limor Livnet, and the heads of the Council for Higher Education called the award winners at the end of the holiday and congratulated them on their achievement. "This is a historic achievement for science and higher education in Israel," said Livnat. "Since time immemorial, Israel has emphasized education and higher education, and its strength has been in the scientific quality it produces and exports overseas. Now it turns out that the 56-year-old labor is bearing fruit." In the coming days, the Minister of Education will hold a celebratory ceremony for the award winners and present them with badges of honor.

However, the cuts in the science budgets and the crisis in which the research universities have fallen indicate otherwise, scientists said after the win. "Not a lot of money goes to science and yet they manage to reach the top of the world," said Prof. Chakhanover. "Today, even less budget is allocated to research, and I hope that the lesson that the country's leaders will produce will not be that 'here, it is possible to do science even under these difficult conditions', but that luckily, despite these priorities, some are successful. If we change the priorities and don't invest the money in lead bullets and bloodshed but in test tubes, it will give us and the whole region an advantage."

According to Prof. Hagit Maser-Yeron, former chief scientist of the Ministry of Science, "This is a very significant and honorable achievement - but it was done despite the conditions and not because of the conditions. If it weren't for their insistence, everyone would have broken down a long time ago and done like the others, going to do the research abroad."

Winning the Nobel Prize is an unprecedented achievement for Israeli scientists. Two years ago, Daniel Kahneman, an American of Israeli origin, won the Nobel Prize in Economics for his research on decision-making under conditions of uncertainty. On Tuesday, David Gross, an American graduate of the Hebrew University, won the Nobel Prize in Physics. Although both of them acquired their scientific education in part in Israel, the scientific work that earned them the prize was already done overseas. On Wednesday, it was the first time that Israeli scientists won the Nobel Prize, the highest honor in the world of science.

The announcement of winning the prize put an end to the feverish speculation in the Israeli science community, which has been going on for several years - who will be the first Israeli scientist to win the Nobel. In recent years, a gentleman's competition has been raging behind the scenes between the Technion and the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, the only two research institutions in Israel where realistic candidates for the prize are currently operating.

Four years ago, Hershko and Cchanover won the "Laskar" prize for basic research in medicine - a prize that, in the field of medicine, is considered second only to the Nobel Prize. Technion executives know the complicated politics of the Nobel and said that "it's better not to talk about it at all." But they couldn't resist and often mentioned, in a whisper, the statistics of the Lasker Awards, which show that in recent years most Lasker winners have also won the Nobel Prize after a few years.

The researchers discovered the "death tag" of the proteins

by Tamara Traubman

Proteins make up all living things - plants, animals and humans. Scientists have studied a lot over the years how proteins are built, but almost nothing was known about what causes them to die? How does the human body know that it must destroy a certain protein, which is damaged or no longer needed, but leave intact another protein, which is still essential?

Professors Avraham Hershko and Aharon Chachanover from the Technion discovered a small molecule, which serves as the "death tag" of proteins. It attaches itself to proteins whose time has come to be destroyed, and signals to the cell that the protein should break down and die. The molecule is called "ubiquitin". The marked proteins are transferred into the cell's recycling basket, known as the "proteasome", where they are chopped into small pieces and destroyed (see figure). This mechanism is so important that without it life cannot exist.

In recent years it has also become clear that disruptions in the ubiquitin system are involved in causing many diseases. Biotechnology companies were quick to recognize the medical and economic potential inherent in this and are trying to develop new drugs against cancer, asthma, hypertension and degenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's based on this knowledge.

One drug - "Valcade", manufactured by the American biotechnology company "Millennium" - has already received all the necessary approvals for its marketing in the USA, and according to Chechenover, "many more drugs are on the way".

Valcade is intended for the treatment of patients with malignant plasma cell cancer, through injections. Hershko and Cchanover say neither they nor the Technion will get to enjoy the future profits, since they did not patent the ubiquitin mechanism. However, Chechenover is today associated with several biotech companies that are trying to develop more new drugs based on his findings.

Almost the entire human body is made of proteins and these are also involved in all processes in the body - they make up the skeleton and muscles, they regulate the timing of every event that occurs in the body and transmit messages between the cells. Some of the proteins - the hormones - trigger some of the emotional and physical reactions. Others tell the body's cells when to form and when to die.

The proteins in the cell are built and broken down at a dizzying rate. "Every day we see the same figure in the mirror," says Chachanover, "but during one day 20-10% of the proteins are replaced, and after two weeks or so all the body's proteins have been replaced and the figure that is reflected in the mirror is already 'not us'."

While the mainstream of the life sciences was preoccupied until about a decade ago with the question of how proteins are formed, Hershko and Chechenover dealt with a question that was less popular at the time: what causes proteins to break down. "Perhaps it took a little courage to go for something that was not in fashion," says Hershko.

The low interest in the field was evidenced by the number of published scientific articles, which reached at least ten per year in the early XNUMXs. Today, the protein breakdown system is of great interest - thousands of research articles are published every year, and biologists agree that it is one of the systems that lie at the base of the mechanism of life.

Chechenover and Hershko, wrote members of the Nobel Prize committee, "helped us understand that the breakdown of proteins is not done randomly but by a process controlled to its details, in which the proteins that the cell is supposed to break down receive a molecular label - ubiquitin."