Success for the first clinical trial in embryonic stem cells

When the embryo is at the beginning of its development, all its cells are identical to each other, and they all have the potential to develop into any type of cell in our body. Since scientists developed the ability to harvest such cells and grow them in the laboratory, the method has been considered a great promise in medicine, because it apparently makes it possible to replace any damaged tissue with the help of the stem cells. However, the realization of the promise encountered many difficulties: from a medical point of view, it was not clear how such cells would behave after being injected into the human body, and there was a serious fear that they would develop into cancerous tumors. Another concern was that the body's immune system would attack the cells, because they are of foreign origin. Added to these was the ethical issue: some consider the fetus, even if it is a few days or a few hours old, a living being, and strongly oppose the taking of the cells, which causes its death. The controversy over the morality of fetal stem cell experiments even led to the suspension of funding for such research in the US for a certain period.

Passersby

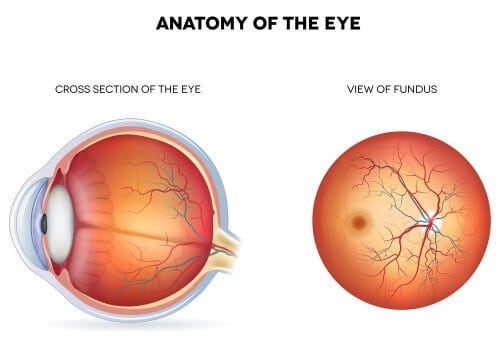

Because of the medical issues, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has only sparingly granted approvals for clinical trials of such treatments. One of the studies that received approval, more than three years ago, was an attempt to treat severe degenerative diseases of the retina using embryonic stem cells. 18 patients with Stargardt's macular dystrophy and age-related macular degeneration, both diseases that cause the gradual destruction of cells in the retina, and eventually blindness, were selected for the experiment. The research was led by researchers from the University of California (UCLA) and Advanced Cell Technology. The head of the research team, Professor Steven Schwartz, first wanted to prove the safety of the treatment, so he chose patients whose vision was already so severely damaged, so that if the treatment failed, they would not risk its deterioration. The researchers used embryonic stem cells grown in ACT's laboratories, and underwent treatments that caused them to begin the process of differentiation into retinal cells. Between 50,000 and 150,000 such cells were injected into one eye of each trial participant. The injection site was chosen partly because it is less exposed to the immune system, in the hope that it will not attack the foreign cells. Along with this, the trial participants also received treatment that suppresses the immune system, to reduce the risk of the cells being rejected.

See eye to eye

After a follow-up of 37 months in the first patients, and up to 22 months in the last patients, the researchers note that no side effects were recorded in the participants of the clinical trial. In four of the treated eyes, a cataract developed, but it seems to be a natural process in patients, most of whom are very old. Two of the patients developed an eye infection, apparently due to the suppression of the immune system. However, there was no immune response against the stem cells, and no cancerous tumors were diagnosed in the participants of the experiment. In addition to proving safety, the researchers were surprised to see a significant improvement in the functioning of most of the trial participants within a few weeks. Some of them returned to reading and were able to walk again on their own after many years of almost total blindness. In an article in the Lancet medical journal, the researchers detail the results of careful vision tests, and state that ten of the patients experienced real improvement following the treatment, and seven experienced some improvement. Only one had a further deterioration in vision. The researchers also point out that the improvement was recorded only in the treated eye, while the other eye was used as a control, indicating that the improvement in vision can indeed be attributed to the experimental treatment. Despite the encouraging results, the researchers point out that this is a small and preliminary trial, and more follow-up and much more research will probably be required before the treatment is approved for widespread use. In the next step, they intend to try and determine the optimal dose, and see if there is a relationship between the number of cells injected into the patients and the improvement in vision.

a source of inspiration

While many scientists are trying to harness the embryonic stem cells for the benefit of medicine, a few years ago a new line appeared in the sky of science. Researchers led by Professor Shinya Yamanaka (Yamanaka) of Pan, proved that it is possible to take almost any normal cell from the human body, for example a skin cell, and with special treatment return it to an embryonic state, from which it can develop into any type of cell. This discovery, which earned Yamanaka the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2012 (with John Gordon), raised new hope for the use of stem cells. First, it solved the ethical issue, because the cells are harvested from the patient's body, and there is no need to destroy embryos. Second, since the cells are taken from the person's own body, there is no reason for the immune system to attack them. Even this method, known as "induced pluripotent stem cells" (iPS for short) is still in its infancy, and far from medical application, but a few weeks ago the first clinical trial began in Japan in a woman who also suffers from age-related macular degeneration. The success of this experiment will give an important injection of encouragement to the young method, and more importantly - the success of both methods will be almost the first clinical proof of the medical effectiveness of stem cells, and a first step in realizing the great promise of the medicine of the future.

A research article in the Lancet journal

Nobel Prize in Medicine for the development of induced stem cells

One response

Stargardt's does not lead to complete blindness, but to visual acuity at the level of 6/120 (non-functional, entitled to a "blind" certificate)

AMD leads to blindness in the center of vision, but the periphery remains normal. As you move away from the center, the sharpness decreases significantly (also entitled to a "blind" certificate in the advanced stage). Blindness is not complete in both diseases.