Most of the great black holes in the universe ate cosmic meals behind closed doors. So far.

The Spitzer Space Telescope, whose infrared eyes are sharper than any previous infrared telescope, managed to penetrate through walls of galactic dust and discovered what they had long been waiting for - the lost population of hungry black holes known as causars.

"The previous studies used X-rays. We expected there to be many hidden quasars but we could not find them," said Alejo Martinez-Sansigre (Martinez-Sansigre) from the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. He is the lead researcher in an article published this week in the journal Nature. "We had to wait for Spitzer to find a whole population of these dust-eating objects."

Quasars are supermassive black holes surrounded by a giant ring of gas and dust. They live in the cores of distant galaxies and can consume up to a thousand stars like our Sun in a year. As the black hole sucks material from the ring of dust, the material glows brightly, making quasars the brightest objects in the universe. Bright light comes in various forms, including X-rays, visible light, and infrared light.

Astronomers have not been able to discover over the years how many of these cosmic beasts (so in the original, the Hebrew word) are there. One of the standard methods to estimate their number is to measure the cosmic background radiation in the X-ray region. Quasars are more luminous than any other object in the X-ray. By counting the X-ray hums the estimated amount of quasars can be predicted.

However, this estimate did not match observations in the X field and also in the visible field of real quasars, the number of which was much smaller than the Pui.

Astronomers thought they existed because most quasars are blocked from our view by gas and dust. They suggest that some of the quasars are located in such a way that their dust rings obscure the light, while the others are buried in dusty galaxies.

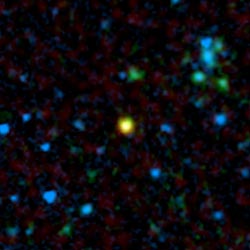

Spitzer appears to have found two types of lost quasars by observing in infrared light. Unlike X-rays and visible light, infrared light can penetrate gas and dust.

The researchers discovered 21 examples of these quasars in a small area of the sky. All of these objects have been confirmed as quasars by the Large Radio Telescope Array of the National Radio Observatory in New Mexico and by the Committee on Astronomical Research and Particle Physics at the William Herschel Telescope in Spain.

"If you project these 21 quasars onto the rest of the sky, you get a huge number of quasars." says Dr. Mark Lisi of the Spitzer Institute of Science at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. and co-author of the article in Nature. "This means that, as we suspected, most supermassive black holes grew while hidden in dust.

The discovery will allow scientists to build a complete picture that will clarify how and where quasars form in the universe. Of the 21 quasars discovered by Spitzer, 10 are inside giant mature elliptical galaxies. The rest are in dusty galaxies and galaxies that are still in their development phase.