They achieved, privately, what most countries in the world are not capable of and reached space. The SpaceShipOne astronaut crew.

Popular Sciences

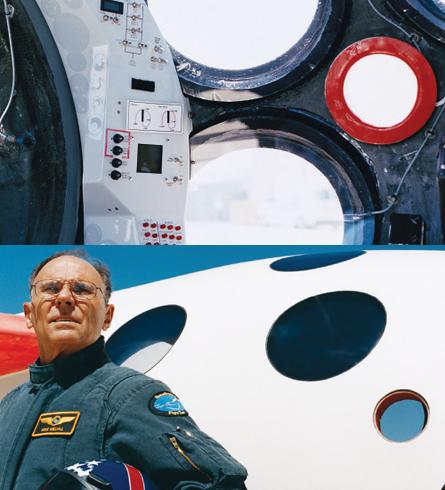

Test pilot Mike Melville and above - a close look at 3 of the 18 round windows of the spacecraft

A tiny rocket plane in blue and white colors glides in a 13.4 km rome above the Mohave Desert. Test pilot Brian Binney, wearing a helmet and wearing a blue flight suit, is focused on the digital display in the cockpit, sneaking only quick glances out through the 18 small round windows. By hitting the switch, he activates the rocket engine, which burns nitric oxide and rubber. The impact is immediate and powerful: Binny is thrown backwards with an acceleration of four G's as his aircraft is shot forward like a missile. In the control center, engineers review the flight data on their monitors. Outside, friends and family look at the rocket's small white exhaust streak in the sky. The engine is barely audible, far away.

The force of the 6,800 kg thrust rocket engine propelling a 2,040 kg vehicle bounces Binny 15 cm out of his seat (the seat belt arrangement was improper, as the engineers later discovered), and caused him to inadvertently pull the steering column . The power also flows the fuel backwards, so the center of gravity is pushed back. The result is a steep and terrifying takeoff that threatens to turn the aircraft upside down. Bini uses slight offset adjustments to lower the nose – moving the steering stick will cause excessive reactions at this speed – and the rudder pedals to minimize drag. Suddenly, silence. The powered phase of the 18-minute flight lasted only 15 seconds, enough to test the engine before gliding back home. When the engine shuts down, Benny, a former US Navy test pilot, is relieved it's over. But it's not over. The decelerating aircraft goes through another cycle of rapid rolls. Benny is putting up with it, but the worst is yet to come. With the adrenaline still coursing through his veins, he speeds toward the Mojave airport, straightens out over the runway and lowers the undercarriage. The wings begin to move from side to side, and Benny's senses tell him that the plane is about to flip. He releases the pressure from the steering rod to try to stop the roll, but it makes him fall faster. When he tries to break the glide over the runway before touchdown, it's too little, too late. It hits the track, hard, and yes - the left passenger collapses. "Spaceship One" skids the runway, veers into the sand, spins and comes to rest diagonally in a huge cloud of dust.

It happened on December 17, 2003, the 100th anniversary of the Wright brothers' first flight at Kitty Hawk and a fitting day for the first powered flight of "Spaceship One." This craft, designed by aeronautical engineer and visionary Brett Rutan, is the key component of a $25 million space program funded by billionaire Paul Allen of Microsoft. It was the front-runner to win the $10 million Ansari X Prize, which will be awarded to the first civilian crew to launch a three-person craft to an altitude of 100 km twice in two weeks. "Spaceship One" did successfully complete this mission on October 4 and Rotan's team received the award. Rotan's radical spaceship is not only the first private spacecraft to reach the edge of space, but the people he has chosen to fly it are the world's first private astronaut crew - seasoned test pilots who struggle with an extremely challenging craft in its first forays into suborbital flight, and experience the All the drama you can expect in such an ambitious experimental show.

After landing, Binny freed himself from his seat, parachute and communication gear, opened the cockpit door and climbed out. His feet sank into the sand. This is not a place where planes should be. The wonderful "one spaceship", created by hard work, deserves the stable support of an orbit, with an uneventful landing as compensation for the difficult flight. And the pilot is entitled to the opportunity to circle the vessel and perform a solemn, albeit cold-hearted, external inspection. Instead, Bini stood there in the blazing sun, surveying the damage to his ship, organizing his thoughts as he waited for the emergency vehicles and support trucks to take him away. Above in the sky, two escort planes circled together with the "White Knight", the mothership that carried the "One Spaceship" aloft. All were flown by Binny's fellow test pilots, including two destined to be astronauts: the veteran Mike Melville, a supremely confident South African who is considered one of the best pilots in the world, and Peter Siebold, a young aeronautical engineer who never imagined he would one day reach the frontier the space. Bini was lucky that the damage to "one spaceship" was not more serious, and that he was not hurt, but he was still troubled by the implications of the incident. How did this happen? Will it jeopardize the plan? And the inevitable question: Did he himself, as revealed to his distinguished colleagues, lose the chance to become an astronaut?

In the months since Binny's flight, "Spaceship One" has been flown only four times: twice by Siebold, who also had hard landings, and twice by the 63-year-old Melville, who earned his astronaut wings on June 21 when he became The first person without government support to fly beyond the Earth's atmosphere. But the decision about who will fly the "one spaceship" has not been made yet. Rotan desperately wants to give Siebold and Binny their astronaut wings, both because they've worked so hard on the program and because he needs more astronauts on his team. Rotan's space program is the first phase, and if he plans a second phase, which he undoubtedly wants, he will need experienced astronauts. Siebold and Binny are much younger than Melville, and thus there is a greater chance that they will be around when Rotan's next-generation spacecraft, built for orbital orbit around the Earth, is ready. But the immediate reality was a $10 million bet, and would it be more prudent to give one or both of the two prize-winning flights to Melville, who excelled in all landings. When the risks Rotan took in high school "One Spaceship" were about to pay off, he now had to decide how much risk he was willing to take in choosing the pilot.

"One spaceship" is actually three tools in one - a glider, a rocket and a spacecraft. It uses different rudders and configurations for each phase of the flight. The transition from one mode of flight to another, as well as almost every second of flight in any mode, requires extreme skills in a flapping aircraft like this - active flying of the kind that modern space shuttle pilots and Soyuz cosmonauts rarely experience during launches, orbital maneuvers, atmospheric entry and landing, which are largely automated. . Fortunately, Rotan has spent nearly three decades creating a small but exceptionally talented cadre of test pilots, people who have flown some of the most unusual instruments ever created, from sports planes with strange configurations to achieve superior performance and record-setting aircraft that circle the world, and including secret military projects and research planes. Some of the pilots flew experimental planes while riding them from above, like on a horse. They were caught in dangerous flat spins, experienced the disintegration of vital components, and completely lost control of the aircraft. None of them even needed a parachute to escape safely from one of Rotan's strange inventions that crashed in smoke on the desert floor.

Now Rotan is making a huge leap from aircraft to spacecraft, letting those who know its tools best fly them into a realm that is completely new to Scaled. This new generation of private astronauts in many ways mirrors those test pilots who became astronauts in the 15s and 2000s: aggressive, highly skilled and competitive, but also fiercely loyal to the mission at hand, and prone to mistakes. The "one spaceship", built somewhat like the X-XNUMX - a rocket plane that flew to the edge of space in the sixties - is an extremely difficult vehicle to fly, even for an experienced pilot. Bini accumulated thousands of hours in difficult military flight tests, and in addition flew another vehicle designed to be used as a spacecraft - the Rotary Rocket Roton, a huge cone with helicopter blades on top that were propelled by rockets. Although Binny is one of the most recent additions to Scaled's team, having joined in XNUMX, he has more formal training than his colleagues, thanks to his military background.

Binny was selected for the test flight in December 2003 because he had the most experience with supersonic aircraft and also oversaw the initial tests of the rocket engine. His troubled landing did not detract from his talent as a test pilot, proven throughout his long career and amply demonstrated in the 18 minutes of flight before landing. But it was a bad place to get into trouble: 10 seconds before touching down on the runway in an unpowered plane, with very little room to right itself. And it cannot be said that Melville and Siebold did not have their own moments of panic in "One Spaceship". They were just luckier in their timing.

Melville – the enthusiastic bespectacled grandpa, who has very little formal training in flight experiments outside of scaled, but is in control of every cockpit he's ever been in – served as pilot during an unpowered flight in September 2003. "Spaceship One" suddenly flipped on its back in mid-air, and went out of control control. To extricate himself, he pushed the tiller forward and tried to lower the bow, which made the situation worse. He forgot that the tail of the plane was designed to keep the nose pointing down, just the opposite of normal planes. It was as misjudged as in Binny's case, but Melville had plenty of time to extricate himself. Rotan's aerodynamics experts fixed the problem by using a larger tail, which they tested when mounted on the front of a Ford F-250 truck that was driven around the track at a speed of 145 km/h. Melville is a co-owner of Scaled Composites and has flown every plane Rutan has designed. He is one of Rotan's oldest and closest friends, and the bonds of trust between them are inseparable. When Melville had a second incident - during a powered flight to Rome of 64.4 km his instrument panel malfunctioned, but he continued the flight in a situation that many pilots would have shut down the engine and returned to the airport - Rotan defended him from the criticism he received.

Rutan says this was one of the main reasons he chose Melville to make the first suborbital flight in June. This flight strengthened the applicability of Rotan's vision, as well as Melville's credit. When the ship reached the peak of the bow at an altitude of 90 km, Melville experienced three minutes of zero gravity. He marveled at the sight of Southern California, and pulled out a handful of M&M's that he had put in his pocket the night before. They hovered in front of him until the ship began its almost vertical dive back into the atmosphere. As the wings flapped upwards, the noise and storm became intense. "I was stunned by the acceleration into the atmosphere," he says. "The feeling was like being in a hurricane. This was the scariest part of the flight. There were a lot of screeching and moaning, and the ship shook so badly that I couldn't even read the instruments."

Melville's choice of pilot to make the first and most historic suborbital flight was not unexpected, given his experience. But it was still bad news for Binny and Sebold. At Scaled, Siebold was able to combine his two greatest loves - flying and computer technology - and turn them into a career. He is like an eager child of the computer age, and he is the one who led the development of the sophisticated flight simulator for the "One Spaceship", the first that Scaled designed and built from scratch, as well as the avionics software for the actual aircraft. The flight simulator, located in a dark room not far from the floor of Scaled's main garage, is a full-scale model of the aircraft cabin - with a carbon fiber chair, instrument panel and a full array of porthole windows, each with a monitor that projects realistic images. It served as both a training facility and an engineering tool, a means of testing and verifying changes to the design of the actual spacecraft.

Siebold's flight simulator has been critical to the training of all three pilots in recent years. But the flight simulator can't help with landings, where you have to practice on a real plane because a lot depends on the movement of the craft near the actual ground. Training flights in "one spaceship" are not a practical option - the cost of each flight reaches several hundred thousand dollars, an amount that eats up a significant part of the prize money - therefore the pilots train in other planes. In the final weeks before the prize flights, Melville helped Beanie practice landings by often taking him in his Long Easy, which almost perfectly simulates the rate of descent of "Spaceship One" on final approach to land. The two pilots even modified the cockpit and canopy of the Long-Easy to simulate the spacecraft's limited field of view.

Following the "One Spaceship" win, Rotan was assigned the task of creating a five-passenger model of "One Spaceship". Rotan, for his part, is already looking beyond the sub-orbital flights, at spacecrafts that can enter orbit in space. He is currently developing an orbital spacecraft that could begin testing within 5 years.