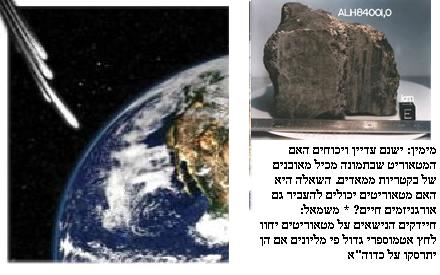

Hardy bacteria make interplanetary travel more conceivable

By: Ariel Eisenhandler, Israel Astronomical Society

The researchers claim that bacteria in rock blocks can survive an impact whose speed exceeds 11 km per second (almost 40,000 km/h). In addition, the study shows that bacteria can survive a crash on icy surfaces, such as those of Jupiter's moons: Europa and Ganymede.

The possibility that the first life on Earth arrived here in rocks from space, a panspermia hypothesis, was proposed in 1903 by the Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius, but the painful landing was always an insurmountable obstacle.

Mark Burchell (Mark Burchell) and his colleagues at the University of Kent in Canterbury (Canterbury) put the "panspermia" assumption to the test by dropping porous ceramic blocks, into which bacteria were introduced, into targets. During the impact the bacteria are crushed up to a million times one atmospheric pressure.

"A few years ago everyone said we were crazy," says Burchell. "They knew it wouldn't work." But in 2001 Burchell and colleagues showed that soil-dwelling bacteria can survive a high-velocity impact into a soft gel. Most of the bacteria died, but enough survived to make the assumption of panspermia possible, as long as they did not have to go through a long journey in space: they were sterilized by cosmic rays and ultraviolet radiation on the journey from another solar system.

the punch

But the researchers did not know if the pressures produced in their experiment were similar to those of a meteorite impact and how other strains of bacteria would react to the experiment. To find out, the researchers used a gas-powered gun to shoot ceramic pieces, whose width ranges from 0.1 to 2 mm, into gel or ice targets. The projectiles (ceramic pieces) were loaded with cells or spores of soil bacteria of the type Rhodococcus erythropolis (Rhodococcus erythropolis) or Bacillus subtilis (Bacillus subtilis) which is a switch, a line-like bacterium. Under impact pressure conditions similar to those of a crashing meteorite, one in 10 million Rhodococcus erythropolis cells and a small number in one hundred thousand Bacillus subtilis survived after hitting the gel. One gram of terrestrial soil usually contains a billion bacterial cells.

The survival rate of hitting an ice target was 10 times higher, so Burchell and his colleagues think that it wasn't just NASA and Mars that exchanged lives. For example: the icy moons of Jupiter, at least one of which, Europa, has an ocean of water below the surface, can fertilize each other. Another possibility is that a planet could re-fertilize itself if, as some have suggested happened across the early Earth, a massive impact wiped out all life (as is thought to have happened about 65 million years ago, during the age of the dinosaurs).