The scientific innovations of the last centuries have taught us that nature can be achieved and even surpassed when one does not try to imitate it. The question before us now is whether this lesson can also be applied to the relationship between the computer and the human brain - the last bastion of human supremacy. Will the machine be able to "understand" in the future?

2.8.2000

By: Zvi Yanai *

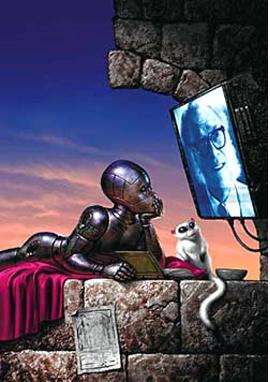

The 21st century will require more flexible and creative thinking than all the centuries that preceded it, because the pace of developments, innovations and inventions is expected to be faster in it than anything we have known until now. One of the obligatory conclusions from this assessment: to guard against any mental fixations. Because fixed thoughts - according to their definition - are the antithesis of thought innovation in general and scientific-technological innovation in particular, since they are based on the assumption that what exists is true, just and proper, and therefore should not be changed. What makes mental fixation dangerous is the fact that time works in its favor. That is, the longer the period of its existence, the greater the chance that it will become an example. And dogmas, especially dogmas with an ideological basis, are like a nail without a head. They represent a state of mental stagnation that may last a long time. This is what happened to Aristotle's geocentric theory. On May 24, 1543, a few hours before Copernicus' death, the first copy of his book "On the Circumferences of the Celestial Wheels" was placed on his bed. Copernicus had finished writing his revolutionary thesis 13 years earlier, but delayed its publication for three main reasons: first, because it contradicted common sense, second, because it went against existing dogma. Third, because it did not agree with the church's position. Let's start with the first: the earth rotates around the sun at a speed of 108 thousand km/h, and around its axis at a speed of 1,500 km/h, yet the houses do not collapse from the force of the wind. This fact obviously does not agree with common sense, and therefore Copernicus had reason to fear that his teachings would be ridiculed. Second, Copernicus' heliocentric model, according to which the sun is at the center of the world, opposes the two-thousand-year-old Aristotelian dogma that placed the earth at the center of the world and moved the sun and the stars around it. Thirdly, his model contradicted the famous verse in the book of Joshua: "The sun stood still in Gibeon and the moon in the valley of Elon", because if the sun was stationary, there was no need to ask to stop its movement. In the end, the heliocentric model prevailed over the geocentric model, but two thousand years late. This is a good illustration of the paralysis of creative thinking by example. Therefore, the question that should interest anyone whose occupation requires intellectual innovation is how to avoid mental fixations. According to the physicist Gell-Mann, the father of the most elementary particles of matter (quarks), the basic condition for thought innovation is the ability to break away from the excessive restrictions of an agreed idea, or in more familiar terminology: the ability to break free from existing concepts. Leonardo da Vinci's idea of attaching wings to man, which would enable him to fly, is a good example of a mental fixation born of a wrong conception. Despite his prodigious creativity and engineering genius, he was unable to break away from the conventional wisdom that the only way to fly in the sky is to fly like a bird. Da Vinci believed that birds were equipped with excess muscle power for emergencies of flight or attack. He was convinced that humans also have more strength than they need to carry their own body weight, and as evidence: on the beach, when we carry a person on our shoulders, we leave footprints in the sand that are less deep than those we leave when looking up. Da Vinci saw this as proof that muscle strength far exceeds our carrying capacity, and that this excess will allow us to fly. Da Vinci's dream was realized 400 years after his death by the Wright brothers, and it was possible because they freed themselves from the concept of the flight of the bird. The Wright brothers copied from nature the convex structure of the wing to ensure the plane the required lift, but they did not use an engine to flap the wings of the plane as if it were a bird. They used it to spin a propeller in the nose of the plane. The lesson from the Da Vinci affair is that nature can be achieved and even surpassed when one does not try to imitate it. This is true in the air, at sea and on land: the helicopter does not try to imitate the hummingbird in order to stay in the air; Man's ambition to swim faster and farther than the dolphin was achieved only after he abandoned oars in favor of sails and propellers; His dream of running faster than the cheetahs only came true after he converted his leg movements to wheels. And the question is whether this lesson can also be applied to the complex and charged relationship between the computer and the human brain - the last bastion of human supremacy. That is, is the way to impart intelligence to a computer not to teach it to think and understand like us, but to pave for it ways that bypass understanding, which can lead to results equivalent to understanding. It seems to me that the computer game of chess, used since the XNUMXs as a kind of litmus paper for measuring artificial intelligence, can illustrate the difference between understanding and equal understanding. In October 1989, Kasparov was asked if a computer could beat a master before the end of the century. "No way," he replied, adding: "To play chess you need more than just tactics and moves, you need fantasy, you need intuition." Without these features, computers have no chance of beating humans in this century. In May 1997, a match was held between Kasparov and an improved version of the previous chess software, which changed its name to "deeper blue". Kasparov lost with a score of 2.5:3.5. "Deeper Blue" did not try to imitate human fantasy, nor our intuition. It presented better algorithms, and above all great computing power which manifested itself in the ability to check 300 million positions per second. Kasparov's loss raises an interesting question: what will happen when simulations that bypass understanding are run on computers capable of performing a thousand billion calculations per second? A trillion calculations per second? According to the rate of increase in calculation power (doubled every year and a half), in 2010 supercomputers will reach the power of the human brain, which represents 100 billion neural connections; In 2060, personal computers will be sold at a price of one thousand dollars, and they will be equal in power to a million human minds. But will these computers only represent incredible computing power, or will they develop forms of understanding and thinking different from ours, immeasurably faster and of higher quality? In other words, will a different form of thinking and understanding emerge from the speed and complexity of these computers, just as our mental capacity developed from the complexity of the human brain? This is an interesting question, but very problematic, because it is doubtful whether we are able to understand a way of thinking and understanding other than our own. Fact is, not only can we not know what a cat is thinking, we can't know what a baby is thinking either. Every good parent tries to deepen the understanding of his children and expand their thinking ability, but he does not create their thinking and understanding. He uses structures of thinking and understanding inherent in them from birth. Furthermore, a significant part of the knowledge about the world is acquired by the children themselves. For example: a child learns from his experience that a toy can be pulled by a string, but it can only be pushed by a rod or by hand. These innate qualities of understanding and thinking do not exist in a computer, and we do not know how to impart them to them. A computer has no innate structures, no senses, no instincts, and it also has no experiences from which new things can be learned. Furthermore, we know that a necessary condition for the existence of understanding and the possibility of thinking is knowing the meaning and content of the information that flows to us from the outside, or that is created within us. This ability does not exist on the computer. For him, an order to start a nuclear war and an order to activate lawn sprinklers differ only in the different organization of the binary signals within the electronic command. This is the state of affairs today. The question is whether in the future, when computers capable of performing a trillion calculations per second will pass a certain critical mass of complexity, will the machine be able to "understand" the content of the information flowing through it by itself, without outside help? I doubt this possibility, according to which intelligence will spontaneously emerge from the complexity of the system. Neither did our consciousness break out completely and all at once from the current complexity of the brain. It matured in a slow process of millions of years, with full harmony between the senses and the mental faculties. Thanks to these interrelationships, we have no problem standing, for example, on the difference between syntactically and semantically valid sentences and sentences that are only syntactically valid. For example: the sentence "The man in the window threw a flower pot" is syntactically and programmatically valid. On the other hand, the sentence "the man against the wall threw a flower pot" is syntactically valid, but programmatically meaningless. The computer does not distinguish the difference between the two sentences, because its life is not conducted in real reality, but in virtual reality, and in real reality, unlike virtual reality, people are not inside walls. But let's assume that consciousness cannot break out of the complexity of a single computer - however sophisticated and powerful it may be - this does not mean that it cannot grow out of the Internet network, which today already represents hundreds of millions of computers and billions of connections. Indeed, there are those who estimate that the global Internet network will eventually become a dynamic system that strengthens and weakens the connections between the various pages of information, depending on their relevance and how much we need them, similar to the process of memory formation in our brains through the strengthening and weakening of signals in the link areas of the brain cells. In this way, and through more intelligent software than the current ones, the network will acquire a thinking capacity much higher than the individual intelligence of each of the network users, because it will be able to gather specific knowledge from hundreds of different areas of expertise for each user. Despite these assessments I maintain my skepticism. For the network to be truly intelligent it needs understanding, and to understand it needs to think. This brings us back to the original problem, to the basic fact that computers, at their core, lack understanding. However, whether the global mind is really smart or only quasi-smart, our dependence on the world wide web will grow. Philosopher Daniel Dent claims that we have already become so dependent on the network that we cannot afford to deprive it of energy and maintenance. This dependence mocks the belief we have cultivated since the fifties of the last century, that whatever happens to our relationship with the computer, our supremacy over the machine is guaranteed forever, because at any given moment the computer can be unplugged from the socket and thereby disable its operation. This was the main message of Kubrick's film "A Space Odyssey". The HAL computer was dying before our eyes as its connectors were unplugged one by one. We will not be able to repeat this exercise in the future, not only because the network does not have a central plug, but also because the global network may impose sanctions on anyone who refuses to provide it with information, by limiting their access to the network or even completely cutting them off from the information.

Zvi Yanai's book, "The Endless Search" (published by Am Oved), will be at the center of the fourth meeting in the "Book Openers" series that will take place on Friday, August 25, at 14:00 p.m. at the Heineken Heima Club. More in the program: Ariel Hirschfeld will discuss his book "Lists on Place"; Tom Segev, Avigdor Feldman and Yehoshua Sobol will deal with "Eichmann in Jerusalem" by Hannah Arendt, and Gal Zeid will read excerpts from "The End of the Century" by Wislawa Szymborska; Anita Shapira will talk with Nissim Calderon about his book "Reluctant Pluralists"; Gali-Dana Singer will read two poems from her new book "To Think: A River"; And Leo Cory will deal with Jorge Luis Borges's book "The Thousand", excerpts from which Gal Zeid will read. The event will be moderated by Yuval Maskin. The entrance is free.

* The article was published in Haaretz, the knowledge site was until the end of 2002 part of the IOL portal from the Haaretz group

One response

Philosopher Daniel Dent is always wrong. The internet can be disabled if you really want to.

B. This blackout from the year 2000 is an excellent example of the over-optimism of Zvi Yanai and those who know for the most part and this is expressed in the next sentence from the article "In 2010 supercomputers will reach the power of the human brain" which today seems ridiculous, because there is still half a year...