Without this original genetic modification, and today's more sophisticated foods, which have been genetically engineered to increase their resistance to disease and pests and increase their nutritional value, our planet would not be able to support more than a negligible minority of the population living on it today

What do we mean when we say "natural"?

In 1980, I went on a week-long body cleansing diet that included water, hot pepper, lemon and honey, which I followed with a 240-mile bike ride, leaving me puking on the side of the road. Neither this diet, nor any of the other crash diets I tried in those days, when I was involved in competitive riding, to improve my performance, worked as well as the "Sea Predator Diet" that my fellow riders followed: "Eat everything you see".

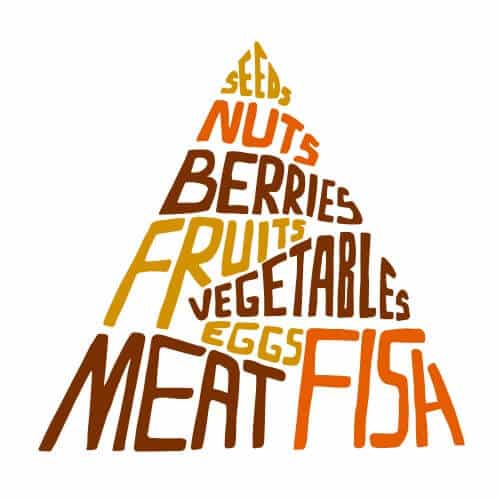

In essence, this was the first diet that could be called a "Paleolithic diet". But it was nothing like the crash diet popular today, which is based on the mistaken premise that there is a single menu of natural foods, in the right proportions, that our Paleolithic ancestors ate. Anthropologists have documented a wide variety of foods consumed by traditional tribes, from the diet of the Maasai tribe consisting mainly of meat, milk and blood to the diet of the people of New Guinea which includes tubers, taro and sago. And as for the relationship between the nutrients, according to a study from 2000 entitled "The relationship between plant food and animal food necessary to maintain the existence of hunter-gatherers around the world and the estimation of the energy value of the nutrients in their diet", published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, their diet includes 22% Up to 40% carbohydrates, 19% to 56% proteins and 23% to 58% fats.

And in any case, what exactly is included in "natural" food? Humans have been genetically modifying food through selective breeding for more than 10,000 years. Were it not for this original genetic modification, and today's more sophisticated foods, which have undergone genetic engineering to increase their resistance to disease and pests and increase their nutritional value, our planet would not be able to support more than a negligible minority of the population living on it today. Golden rice, for example, which has been genetically modified to increase the vitamin A content, was created, in part, to help children in the third world who suffer from a nutritional deficiency that causes the blindness of millions. And regarding the health and safety concerns of genetically modified food (GMO), according to a report published in 2010 by the European Commission under the title "A Decade of Genetically Modified Food Research Funded by the European Union":

The main conclusion that can be drawn from 130 research projects over 25 years, which included more than 500 independent research groups, is that biotechnology, and especially genetic modifications of food for themselves, are no more dangerous than routine methods of plant breeding.

Why then are so many people in a state of near moral panic regarding genetically engineered food? A possible explanation can be found in the four types of relationships proposed by anthropologist Alan Fisk from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) as part of his relationship model theory: (1) cooperative sharing (equality between people); (2) ranking of authority (between superiors and their subordinates); (3) equal matching (one-for-one exchange); and (4) market pricing (from barter transactions to money). Our Paleolithic ancestors lived in egalitarian groups where they usually shared the food equally among the members of the group (cooperative sharing). As these bands and tribes united into governments and states, unequal distribution of food and other resources became common (ranking of authority) until the system shifted to market pricing.

Violations of these relationships help to understand how genetically modified food becomes more of a moral subject than a biological entity. Roommates, for example, tend to eat only their own food or exchange consumed items between them (equal adjustment), and perhaps spouses share among themselves without calculation (cooperative distribution). If you invite friends over for a meal, it would be awkward if they offered to pay for it, but if you dine in a restaurant, you must pay and not invite the owner of the house to your home for a similar meal. All four types of relationships are rooted in our natural desire for fairness and reciprocity, and if something is perceived as a violation of these, it creates a sense of injustice.

Given the central place of food in our survival and prosperity, I suspect that genetically modified food is seen as a violation of cooperative distribution and egalitarian adjustment, especially given its link to large corporations like Monsanto that operate according to the relational model of market pricing. Moreover, following the elevation of "natural" food to an almost mythical status, combined with the taboo that burdens some methods of genetic modification - do you remember the days when in vitro fertilization was considered unnatural? - The genetically modified food is considered almost sacrilege. And it shouldn't be that way. The use of this food is scientifically sound, nutritionally valuable and morally noble in helping humanity in a time of population growth. And in the meantime, eat, drink and enjoy your lot.

About the author

Michael Shermer is the publisher of Skeptic magazine (www.skeptic.com). His new book: "The Moral Noah's Ark" was recently published. Follow him on Twitter: @michaelshermer

The article was published with the permission of Scientific American Israel

6 תגובות

Tzur

Saying you're against genetically modified food just shows you don't have the faintest idea what you're talking about. And to slander modern medicine is impudence mixed with stupidity.

If you have a concrete argument, which is based on facts, then talk about it, and don't slander in a blanket way. The same medicine that you underestimate triples your life expectancy. Your disdain is really irrelevant.

Non-GMO and pesticide-free organic corn, appetizing

https://www.facebook.com/Meat4All/photos/a.545152075507588.1073741828.544822185540577/971197016236423/?type=3

Tzur T - Please, first of all, grow food commercially and then give learned advice.

Thanks

Hi Zion, I agree with you by and large.

I am not in favor of a total denial approach. As you mentioned, the negative should be of foods that have not been tested properly,

But here the question arises as to how one decides what has been properly tested.

Hence the answer is subjective.

My personal answer, based on the concept I developed, is that in most cases I would not trust the food companies

What is at the forefront of their minds is profit and not the modern scientific medical establishment, which, in my opinion, still understands too little about the human body. Why do I think so? That's another discussion.

At the same time, it is important to ask the question, why is it necessary to engineer food? If the answer is "to save the producers costs, such as irrigation, pest control, etc.," then in my opinion the risk is not worth it. If the answer is to provide food for a growing world, then this is indeed a worthy goal. However it is important to ask, isn't there another way we can do this? For example, the food problems in the world today are not necessarily a difficulty in food production, but a political matter. Therefore, if the problem can be solved in other ways, and I hope so, then genetic engineering can be left in the research framework, and abandoned as a solution to humanity's food problems.

flint

Deciding to do nothing until we fully and completely know how the human body is built, and what affects it, is a crazy conservative approach. Almost everything created is the result of trial and error and improvement, otherwise we would remain in the jungle.

In the genetic diversity that exists in billions of people, there will always be something that affects someone.

If you are rich enough, you can only consume supposedly non-GMO food. But are you sure it wasn't engineered? Are you convinced that the genes of your tomato have been the same for thousands of years? Do you even have the ability to know how the genetic information of what you eat developed? You can know that certain varieties of certain foods come from such and such commercial sources, even if you avoid them, everything you eat is the product of thousands of years, which you only know what happened to it in the last few years.

Wouldn't you try a drug that would save your life with an 80% probability?

Therefore the negation should be of foods that have not been tested properly. If we wait for the certainty of everything, we will not progress anywhere. Some will pay a price, but many will benefit.

There is no 100% in anything. We take risks at any given moment

As someone who opposes genetically modified food I think Michael Shermer missed the main point.

Although I only represent my opinion, and I don't know what others think, but for some reason it doesn't seem to me that the main objection is the fairness in relation to the food, but the health concern.

The starting point is that the human body is a very complex system. We know a great deal about her, but it is still very little.

We know many details, but do not understand well enough how all these details affect each other.

This is the reason, for example, that almost every drug we create has side effects. We still do not know the connections between body systems well enough to be able to change one thing for the better without changing another thing for the worse.

Man has evolved over thousands of years of evolution so that his systems adapt to the food in his environment.

Genetic engineering may disturb this balance and create properties in food that have a negative effect on human health.

The opposition to genetically modified food is not an absolute opposition that claims that genetic improvement cannot fundamentally be beneficial. Of course, theoretically, genetic improvement is possible which is beneficial, but as I explained before,

As long as we do not understand the systems of the human body in a sufficiently complete manner, so as not to create side effects (and the pharmaceutical industry illustrates to us how far we are from this), we can with great certainty expect side effects as well

as a result of genetic engineering.

By the way, the improvement of food by hybridization is also not perfect in terms of health problems. For example, we have developed varieties of vegetables that are larger, but nutritionally poorer.

However, the assumption is that the damage that may be caused by genetic engineering may be much greater than crossbreeding, because while in the second case we select and crossbreed based on the food that evolution has created over thousands of years,

In genetic engineering we do "what's on our mind".