German and Greek scientists have discovered that huge earthquakes occurred in the geological past around the island of Crete where the Aegean subplate rubs against the African plate. A warning light should also be lit in Israel

A new study states that the eastern Mediterranean basin is more seismically active than previously assumed. On a geologic time scale, seismic activity around the island of Crete has caused large earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, a figure that may increase the future risk of earthquakes and tsunamis in the area. This is according to a new study published in GEOPHISICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, the journal of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

The Mediterranean basin consists of several tectonic plates that are the result of the collision between the African plate and the European plate. The interaction makes the eastern Mediterranean a particularly earthquake-prone region, but scientists have been puzzled by the fact that the region has experienced only two known earthquakes greater than 8 on the Richter scale in the past 4,000 years.

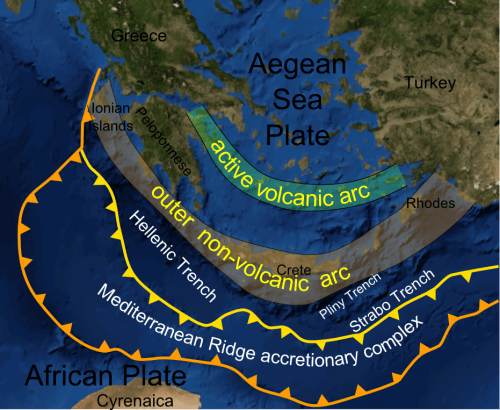

In the south of the island of Crete, the African plate lands beneath the Aegean subplate in an arc-shaped area known as the Hellenic Gap. In the new study, researchers traced the history of the earthquake in this subduction system to gain a better understanding of key processes that drive the generation of megaearthquakes in the region as well as how often these events occur.

"We discovered that the margin of the Hellenic subduction zone is active on a once-in-50-year cycle, about 10 times the time window of the paleoseismic earthquake observations in the eastern Mediterranean that we had in the past," said Vassili Mouslopoulou, a geologist at the German research center GFZ Geosciences in Potsdam, Germany. , and the lead researcher. "For the first time ever, we were able to map a pattern in space and time when mega-earthquakes ruptured the Hellenic interval."

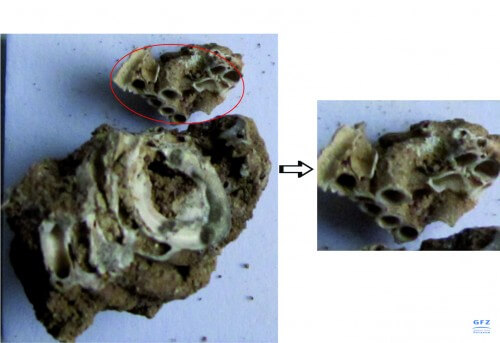

In this study, the researchers combined field studies with radiometric dating and numerical models to examine the gap that opened on the island of Crete. The scientists identified remains of the ancient beaches along Crete, which today are up to 23 meters above sea level. "Each coastline at a relative height above sea level reflects the total vertical movement of this area due to the earthquakes," say the researchers.

By radio-dating the marine fossils captured along each ancient coastline, the researchers found that over the past 50,000 years, both the western and southern coasts of Crete have uniformly risen to 100 meters above sea level due to at least forty earthquakes with magnitudes greater than 8 on the Richter scale. . The source of these tremors was offshore, on the three seismic transects that stretch along the western and eastern parts of the Hellenic subplate margin, according to the new study.

The new study shows that the replicas on the eastern side of the margin are capable of producing large earthquakes, and do not slide on top of each other without producing seismic shock waves, as previously thought. This means that the seismic risk in the eastern Mediterranean is significantly higher than scientists previously assumed, according to the researchers.

However, another surprise was the concentration of earthquakes in clusters. "We also found that, unlike most subduction zone margins around the world, large earthquakes in the Hellenic interval were clustered in time," Moslopoulou said. "The data show that most of the earthquakes occurred over a period of about 10,000 years, and there were long periods (up to 20,000 years) of relative seismic silence."

The new study reveals, for example, that the replicas beneath western Crete appear to have returned every 4,500 years on average for the past 50 years, with the frequency increasing to one in 1,500 years between 20 and 5,000 years ago. Between 3,000 years BC and the beginning of the AD no earthquakes were recorded. The other two replicates showed a similar pattern, the researchers say.

The high variability in the occurrence of large earthquakes in this region makes calculating their recurrence a great challenge, according to the researchers. Therefore, while the Hellenic margin is currently experiencing a seismically quiet period, the study indicates that large earthquakes can be expected in the future under the levees on the eastern and western coasts of Crete, and it is worth considering the installation of protective measures such as tsunami warning systems and earthquake-resistant construction, due to the renewed risk assessment.

Israel is also (together with the Sinai Peninsula) on a sub-plate belonging to the African plate. We are not that far away, and it is also clear that a strong earthquake in Crete means at least a strong tsunami in the Mediterranean Sea. It is desirable that the policymakers take the same precautions, and preferably one hour earlier.

2 תגובות

To the scientific prediction it is certainly possible to add ancient stories of the Greek and Jewish culture, with improbable events such as the Philistines who came and were called the "Sea Peoples", with stories about Atlantis that disappeared under the water, legends about the people of Israel that crossed the sea that disappeared, etc. The dating of the stories can improve the calculation of the expected recurrence.