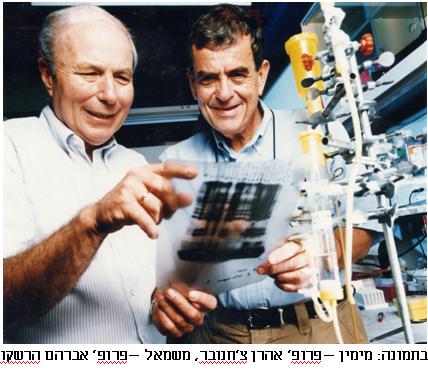

"The essence of my life is closing knowledge gaps" a conversation with Prof. Aharon Chachanover - 2004 Nobel Prize Winner in Chemistry

What is the reason why the Nobel Prize for deciphering the protein breakdown mechanism was awarded so many years after the basic research on the subject? Do you expect a renewed momentum in this field?

I don't sit on the committees, and I don't know their judging mechanism. In hindsight, the passage of time was in our favor because for the first seven years it allowed us to work quietly. People just didn't believe us, and only in the early 90's did they realize that there was something important here. The Nobel committee always looks at big rivers, and after it discovers a big river, it checks what the source of its species is. Today, entire books are written about the system, tens of thousands of articles and many conferences are held. I think it just took ten years for the system to penetrate the consciousness and due to its time.

Science works quite a lot according to fads, and people before us did ask why proteins break down. After Christian de Doub discovered the lysosome, an intracellular organelle that contains protein-degrading enzymes, and received a Nobel Prize, scientists thought the problem was solved - we found the garbage disposal mechanism. Then evidence began to arrive that the lysosome actually does not answer questions asked about protein breakdown. In the 70's it became clear that there are proteins with different stability, and the lysosome is unable to explain this. They then began to discover inhibitors of the lysosome, and it turned out that they only inhibit the breakdown of proteins that come from outside the cell. Science is a profession that requires a very long breath. And we have to wait for the accumulation of evidence to establish an assumption. Then they concluded that there must be something else besides the lysosome. If an American president comes today and says take 100 billion dollars and within a year bring me a cure for cancer - you will not succeed. Neither in 100 nor in 1000 billion dollars, because there are missing building blocks that cannot be skipped over, we are not prophets.

But what made you both stick to the topic even though not everyone was involved in it?

The original idea to work on the subject was Avraham Hershko and Gordon Tomkins (from the University of California and the American Institutes of Health - the editors). The decoding of the system was ours. There were all kinds of strange phenomena, for example that the system required energy. Why is it that a process that releases energy requires more energy? So there were all kinds of ideas. For example, the hydrophobic lysosome has to cross a hydrophobic membrane, and for that you need energy. There was uneasiness in the field, and Abraham Hershko entered it and I joined. So the breakthrough began along with other people and Irwin Rose of course who solved the enzymatic problem for us. At every stage there was a rationale - scientists are very rational people, information gaps cannot be skipped. Our advantage was that we looked at the facts correctly, and others did not. But we didn't invent any fact, we didn't invent anything.

The sequence of amino acids in ubiquitin is jealously conserved in many organisms. This usually happens in a protein that has a very important role, such as hemoglobin, why does this happen in ubiquitin?

Right, that's one answer. A second answer is that ubiquitin has many functions, related to the targeting of proteins. This is a protein that has to serve many masters and should probably go down to the lowest common denominator to serve them all. Any change or mutation that happened created a protein that could not function in all the processes, and it did not survive. This may also be why ubiquitin is small, because each size adds an additional evolutionary complication.

Where do you see the best chance today to exploit the mechanism for medicinal purposes?

There is already a drug on the market today. She is good in terms of marketing but her idea is not good. The drug inhibits a process common to all ubiquitin processes - the action of the proteasome. I think the future lies in a previous step: in the enzymes that recognize the proteins destined for degradation and bind the ubiquitin. The linking processes are very specific processes and this is therefore the ideal system for attack, and it is indeed under heavy attack today by all the pharmaceutical companies.

So what are you researching today?

I'm still researching the ubiquitin system. We work on transcription factors, for example NF-kapaB which is a very important transcription factor in the immune system and the cancer system. It is an anti-apoptotic factor (apoptosis - initiated death of cells, cell "suicide" - the editors). Therefore, its high expression does not allow the cells to die. One of the problems with cancer cells is not rapid division but insensitivity to programmed cell death, and we are working on these processes. In 1998 we discovered that ubiquitin binds not only in the middle of the protein chain but also at the end. The question was "why?" In the meantime, we were joined by large research groups in the world and 13 or 14 very important proteins were discovered that are broken down through ubiquination at the end of the protein. So suddenly we made another breakthrough.

We wanted to offer you a Hebrew name for ubiquitin - Nafusun.

Common, or, yes, I embrace it… [laughs].

Some have defined the award as a new era for science in Israel, do you share the definition?

I do not share any definition of black and white. Science everywhere in the world depends on funding. And funding comes primarily from governments. A country whose government does not fund science has no existence - it will die physically. It may be that as a result of Israeli scientists winning the Nobel Prize, the government will think that there might be some value to science after all. And it's not just science but education in general. If you invest in kindergarten you will get a better student in elementary, and if you invest in elementary you will get a better student in high school, if there are good high school students then better students will come to university. And if at some point you broke the chain then you destroyed the whole thing. But there are no shortcuts. Knowledge is to sit down, read and delve into and understand processes. And you have to invest a lot of money in this, in the whole system from its beginning to the most advanced scientific research. It is serious to me that we need Swedes to determine our national-social priorities. The ubiquitin system was there and its importance didn't change once it got a Swedish goshpenka.

So what do we do to leverage education?

I do not know. I'm not going to become a politician, but stay in my lab, and do things that interest me. The biotechnological industries related to the ubiquitin system fascinate me very much. The industries are able to leverage things that academia cannot finance - to combine research with application.

And regarding education I will help with the little time I have. I'm not going to be a teacher, but of medical students and doctoral students. Along with the prize, they did not give me a magic cube to solve the problems of the State of Israel.

I was asked what I miss? I answered that the end of the 50s. We also brought immigrants, we also put them in the crossings, rain also leaked on them and they also caught pneumonia... And the teachers were excellent. I had excellent teachers. We are in social decline. In the time I have left to live...let's say I have 13 more productive years...I want to spend them in the lab making scientific discoveries.

Last question - you went through many interviews. Is there a question you would like to be asked but wasn't asked?

No, there are questions I'd rather not be asked at all, like what will I do with the money? And all kinds of nonsense like that [laughter]. But there was one very good question, and that is what is my dream? And my dream is to fall asleep now and wake up in 500 years. Because I want to know how the problems we face today will be solved. Will the mechanism of Alzheimer's be discovered and how will it be treated? Will cancer in 500 years become a headache? You will be diagnosed with cancer, take an aspirin and forget. Or a variation of the dream: every 500 years to wake up for a short time to look and return. in quanta. To see where humanity is developing. And here really the prophecy was given only to fools. We cannot cure Alzheimer's, because we do not know what Alzheimer's is, and we cannot skip knowledge gaps. This is what I do myself, I close knowledge gaps. The essence of my life is closing knowledge gaps... The last century is exponential in everything related to knowledge. But I would like to make a quantum leap, and these leaps I cannot make. And for that I am very sorry. It's too slow for me. But this is life.

Members of the Scientific American Israel system participated in the conversation with Prof. Aharon Chachanover: Dr. Eli Eisenberg, Dr. Deborah Jacobi, Dr. Eitan Crane and Dr. Alex Manes.

About the award:

Aharon Chachanover and Abraham Hershko from the Technion, doctors by training, and biochemist Irwin Rose from the University of California at Irvine won the prize for deciphering the biochemical mechanism for breaking down proteins in the cell. A living cell breaks down foreign proteins into their building blocks, the amino acids, in a process that does not involve the investment of energy. But at the end of the 70s, the laureates encountered another mechanism, which requires the investment of energy, in which the cell breaks down its own proteins. The researchers linked the new process they discovered to a small protein discovered a few years before, a protein found in almost all nucleated cells. The protein was therefore named ubiquitin derived from the Latin word ubique which means "everywhere".

In the study, it became clear that the cell recognizes the protein destined for degradation through three enzymatic steps (one of which consumes energy) and marks it by attaching it to a short chain of ubiquitin molecules. This "tail" serves as a hallmark of the "death sentence" imposed on the protein. An intracellular organelle called the proteosome recognizes the ubiquitin chain as a lock recognizes a key, and lets in the protein that received the "kiss of death". Protein-degrading (proteolytic) enzymes found within the proteasome cut the protein into segments of five to seven amino acids.

Deciphering the mechanism can serve as a basis for the development of drugs based on different stages in the mechanism, drugs that can delay or speed up its action according to the need dictated by the cure of the disease.

https://www.hayadan.org.il/BuildaGate4/general2/data_card.php?Cat=~~~76156398~~~186&SiteName=hayadan