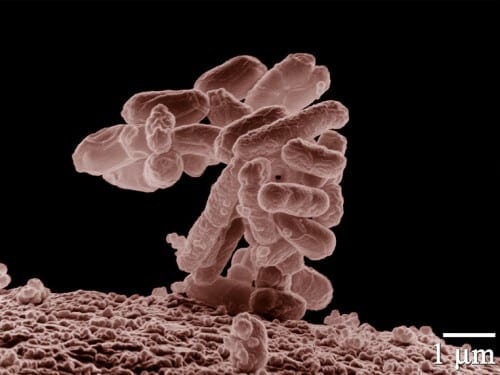

A new examination of the microbiome bacteria may help in the development of targeted treatment methods for various diseases

The microbiome in our digestive system - the set of bacteria we carry in our intestines - has already been linked to various phenomena and diseases, from obesity and diabetes to heart disease, as well as neurological disorders and cancer. A significant part of the research in the field is focused on the many types of bacteria that inhabit the microbiome, with the aim of examining which of them may be involved in various diseases. But the Weizmann Institute of Science scientists chose to examine the field in a new way. In a new study published today in the scientific journal Nature, they asked: "What if the same bacteria differs from person to person?"

It is already known that the genetic sequence of bacteria, unlike our genome, is much more subject to changes. The bacteria can lose some of their genes, exchange genes with other microorganisms, or receive new genes from their environment. Thus, a detailed comparison of the genomes of apparently identical bacteria will reveal DNA sequences that appear in one genome but not in others, or sequences that appear once in one genome and many times in others. These differences are called "structural variants". Structural variants – even the smallest of them – may cause the development of significant differences in the ways in which the bacteria interact with their human hosts; A variant may, for example, turn a friendly bacterium into a pathogenic one, or give it resistance to antibiotics.

People whose microbiome contained a certain variant in the genome of one of the bacteria were six kilograms thinner and had four cm narrower waists, on average, than people with the same bacteria - which did not contain the same variant.

Dr. David Zaevi and Dr. Tal Korem, first in Prof. Eran Segal's laboratory at the Weizmann Institute of Science, and later in their current positions at Rockefeller and Columbia Universities, developed algorithms that systematically identify structural variants in the microbiome. The researchers began work on samples from approximately 900 Israeli subjects; and managed to identify more than 7,000 variants. Then, in collaboration with researchers from the University of Groningen, the Netherlands, they looked for these variants in the gut bacteria of a large group of Dutch subjects. Most of the structural variants identified in the Israeli subjects were also found among the Dutch, despite the differences in genetics and lifestyle between the two groups of subjects.

The researchers then asked whether the structural variants they identified were associated with health or disease states. They found more than 100 such variants, which were associated with disease risk factors. Many of the connections were also found in the Dutch group.

In one case, people whose microbiome contained a particular variant in the genome of one of the bacteria were six kilograms thinner and had narrower waists by four cm, on average, than people with the same bacteria - which did not contain the same variant. Later, the researchers analyzed the genes encoded in this variant and found that it gives the bacteria the potential ability to turn certain sugars into a substance called butyrate. Butyrate is a small fatty acid that smells like rancid butter (its name is derived from the ancient Greek word for "butter"); Despite the smell, butyrate has proven anti-inflammatory effects and a positive effect on metabolism. This ability, the scientists say, may help explain the difference in the weight of subjects who carry the bacteria with the structural variant and those who do not.

The findings indicate that the method developed by the research group can be used by researchers in their efforts to locate the connections between the microbiome, and our health and illness in significant ways that are missed by other methods. "The real potential of this approach," says Dr. Zeevi, "is that it allows us to look for the mechanisms behind the relationships we identify."

Prof. Segal estimates that there may be tens of thousands of structural variants within the microbiome of the human gut, and thousands of them may have a connection to diseases and risk factors for diseases. Because the composition of the microbiome is implicated in many different syndromes and disorders, this research may have a lasting impact on the search for more targeted disease treatments.