Meet BUM, a new underwater microscope that for the first time recorded rare images of coral fights, corals that "kiss" and algae that cause coral bleaching

By: Ben Yishai Danieli, Angle - news agency for science and the environment

The desire to expand human knowledge and deepen our acquaintance with the world in which we live brought man to the depths of the sea and to the edge of the solar system. But while telescopic lenses bring us images of distant stars, there are hidden processes that are much closer to us, and are too small to be seen with the naked eye. BUM (acronym for Benthic Underwater Microscope) is a new underwater microscope, which was developed in collaboration with an Israeli scientist and allows for the first time to photograph microscopic processes that take place on the seabed in high quality and reveals a series of intriguing films and spectacular images.

bring the laboratory to the sea

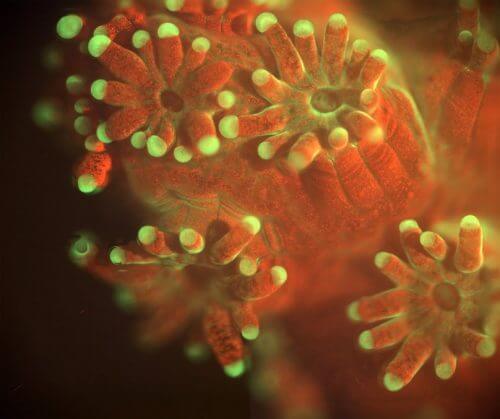

Many processes that happen underwater occur on a microscopic scale. "Corals, algae and sponges are things that are not usually thought of as something 'small', but they are made up of tiny parts," explains Dr. Tali Treivitz, head of the underwater imaging laboratory at the School of Marine Sciences at the University of Haifa, who was a partner in the development of the BUM microscope . "Corals are colonies made up of tiny units called polyps. The polyps can reach a size of a millimeter or even less. If you want to look at them and see what they eat or how they prey, you need a microscope. The problem is that coral is a very spoiled creature that is difficult to grow in a laboratory. It is necessary to create a controlled system of temperature and light, and even then it is difficult to imitate the complexities of the environmental conditions of the sea. The new microscope allows researchers to study the corals without taking them out of their natural environment."

The microscope is the product of development by a team of scientists from the Scripps Institution for Ocean Research at the University of California, in which Treiwitz was a partner. The microscope was developed over a year, and was built so that a diver could operate it with maximum comfort. It consists of two parts: a photography unit, which includes a camera with a microscopic lens and a ring of LED lights, and a control unit which is basically a small computer in a waterproof case. You can even find an LCD screen and control buttons with which the diver can see the image live and adjust the exposure time and the sharpness of the image.

Many corals, kissing corals

The microscope is the first device that makes it possible to document processes on the seabed at the level of the individual cell - up to five microns in size (a micron, or micrometer, is a unit of measurement one millionth of a meter, or thousandth of a millimeter). "You can use it to photograph corals, sponges and algae in a way that has not been possible until now," Treivitz says. Meanwhile, the microscope took unique pictures from the Gulf of Eilat and the island of Maui in Hawaii.

During the experiment in Eilat Bay, the microscope recorded how corals fight each other for territory. "It is known that there are coral species that find it difficult to live next door, because they fight for space with each other," Treivitz explains. "In the photos we took, you can actually see the stages of development of the battle between the corals: it starts with groping, as if they are testing each other, and slowly the battle develops and becomes more and more violent, until one of them attacks the other with hunting arms to kill it. This is the first time that such a process is photographed in such a high resolution and for such a long time - a whole night. In the movies, you also see that corals of the same species do not touch each other, because they have a chemical mechanism that tells them that it is a friend and not an enemy."

Along with the underwater war, the microscope also recorded a phenomenon known as the "coral kiss": coral polyps in the coral colony touch each other, in what looks like a gentle kiss. This is a process that usually occurs in the evening or at sunset, due to the entry of water into the coral tissue, which causes it to swell.

In Maui, the microscope provided a close look at one of the destructive processes that coral reefs go through in the world: coral bleaching (a process known in English as Bleaching). Because of warming ocean waters, the cooperative algae that provide nutrients to corals leave the coral's body, turning it white. "The microscope allowed us to follow the coral over time, and thus see how the algae that give the color to the coral begin to leave, and how other algae begin to take over it," says Treiwitz, who also explains that the new algae taking over the coral thwarts the possibility of its restoration from bleaching, leaving intact parts of the reef When they are completely white.

There are currently two prototypes of the microscope, one in the laboratory in San Diego and one in Israel, in Treiwitz's laboratory at the University of Haifa. The laboratory continues to work on improving the capabilities of the microscope so that it can photograph phenomena in a new way, and works in collaboration with marine biologists to continue to study the microscopic processes that occur on the seabed.

In the future, the researchers hope that it will be possible to connect the BUM microscope to unmanned underwater tools that are operated remotely, so that it will be possible to take close-up pictures of tiny processes at depths that cannot be dived to. It is also possible that the microscope could be used in the future for a completely different purpose: detecting seawater impurities, such as tiny plastic debris.