An expert from Switzerland discovered that it is possible to extract fetal DNA from the mother's blood, thus saving a very invasive treatment that may also harm the fetus

A non-invasive blood test can now detect a gene for the serious disease beta-thalassemia in a developing fetus. The developers of the method believe that the method can be used to detect a wide range of genetic diseases, thus overcoming the need for the more invasive method - amniocentesis.

A scan of the mother's blood can determine whether an unborn baby carries certain hereditary diseases. But currently used scans can only detect large-scale changes and aberrations on the fetus's chromosomes, such as those found in Down syndrome, says Sinoa Hahn, a molecular biologist at the University Hospital for Women in Basel, Switzerland.

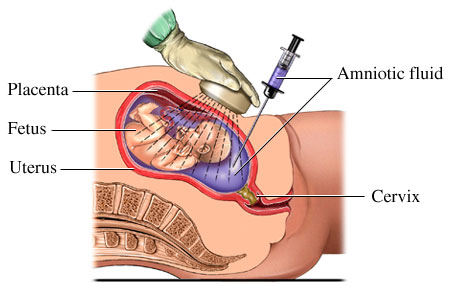

Doctors use amniocentesis to detect mutations in a single gene, such as those that cause beta-thalassemia. The test involves inserting a needle into the mother's abdomen to draw benign fluid from the uterus. However, this invasive method may lead to damage or loss of the fetus in 1% of cases (that is, there is a fear that the pregnancy will be harmed in 100 case out of XNUMX cases of amniocentesis).

Hahn and his collaborators found that tiny fragments, in tiny amounts, of fetal DNA can be separated from the maternal genetic material found in her blood. This allows them to examine the presence of individual mutations in the fetal DNA.

Separation by size

The researchers took blood samples from 32 women in southern Italy who were in their 12th week of pregnancy. The family history of these women indicated that their fetuses were at risk of being born with beta-thalassemia, a fatal inherited disease that stops red blood cells from producing hemoglobin molecules, which are essential for carrying oxygen.

Last year, Hahn's group found that the mother's DNA segments tend to be much larger than the fetus's. Although maternal and fetal blood do not mix directly, the placenta sheds approximately 8 grams of tissue each day, releasing fetal DNA into the mother's bloodstream.

The researchers separated the maternal and fetal DNA in the blood samples using a process called electrophoresis, during which molecules are carried along a long strip of gel by an electric current. The smallest segments were sterile of fetal origin, and allowed the researchers to correctly identify the presence or absence of the mutation that causes beta thalassemia in 93.8% of cases. These findings were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association1

Recessive inheritance

The allele (copy of the gene) responsible for beta-thalassemia is recessive, so a parent can carry one copy of a mutant gene and function as a healthy person for everything. However, if a baby receives two mutant copies, one from each parent, he will develop the disease. There are more than 200 known mutations whose occurrence impairs the function of the gene and may cause beta thalassemia. Any combination of 2 defective copies, even if by different mutations, will lead to the appearance of the disease.

Despite the difference in the size of the segments, there is still a risk that maternal DNA will be mistakenly identified as fetal DNA, and since the mother carries one mutant allele (gene copy), a situation may occur in which the fetus will be identified as blue even though the defective copy belongs to the maternal DNA. Because of this risk, Hahn explains, the researchers looked for proof that the short DNA segments contained the father's mutation. In this way, it can be said with certainty that the presence of a characteristic mutant segment of the father in the mother's blood originates from the fetal DNA. In the unlikely event that the parents have exactly the same mutation, the test does not give a definitive answer, but Hahn believes further research will overcome this problem as well.

Aubrey Milonsky, director of the Center for Human Genetics at the Boston University School of Medicine, points out that even in an amniotic fluid test, the need for paternal DNA sometimes arises to determine with certainty point mutations characteristic of the father and mother. However, he warns that the new method still needs to prove itself.

2 תגובות

Definitely an interesting topic, I will deal with it in my blog intended to deal extensively with the subject of amniocentesis.