Researchers from Tel Aviv University tested using an algorithm they developed 16 inscriptions from the Tel Arad site, and discovered that they were written by at least six different hands

"The results of the study show that in a remote citadel in the Be'er Sheva Valley, writing was common," says Prof. Israel Finkelstein. "From the content of the letters we learn that literacy has penetrated to low levels in the military administration of the kingdom" The new study will be published during the coming week in the prestigious journal:

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

What part of the population knew how to read and write during the Kingdom of Judah? And what are the implications of this for the date of composition of biblical texts such as the books of Deuteronomy, Judges and Kings? Researchers from Tel Aviv University used innovative algorithmic tools to test the level of literacy at the end of the Kingdom of Judah.

The special interdisciplinary research was conducted by the doctoral students Shira Feigenbaum-Golovin, Aryeh Schaus and Barak Sober, under the guidance of Prof. Eli Turkel and Prof. David Levin from the Department of Applied Mathematics, while collaborating with Prof. Nadav Naaman from the Department of History of the People of Israel and Prof. Benjamin Zass From the Department of Archeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures. The research group was headed by Prof. Eli Pisetsky from the School of Physics and Prof. Israel Finkelstein from the Department of Archeology and Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations.

The research will be published during the coming week in the prestigious journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences).

"There is a consensus in modern research that many of the biblical texts were written after the events described in them," explains doctoral student Aryeh Shaus. "But there is a lively debate whether biblical books such as Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings were compiled already in the last days of the kingdom of Judah, or only after the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians. One way to settle the debate is to ask when there was the potential for writing complex essays such as these. After the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BC, we find very little archaeological evidence of Hebrew writing in and around Jerusalem. However, from the period of time before the destruction of the house there is an abundance of written documents. The question is who wrote these certificates. Is it a literate society, or is it a handful of literate people?"

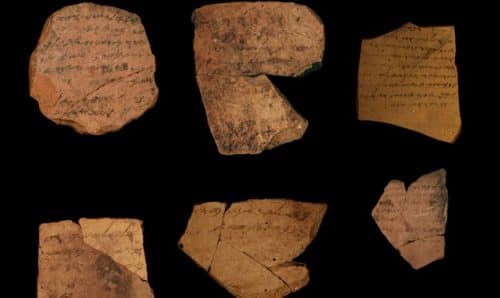

To answer this question, the researchers used state-of-the-art image processing and computer learning technologies to examine the Arad writings: ostracones (fragments of pottery with ink inscriptions on them) that were uncovered at the Tel Arad site in the XNUMXs.

"Tel Arad was a military fortress in a peripheral area of the Kingdom of Judah," says doctoral student Barak Sober. "This is a fort built on an area of about two dunams, where about 20 to 30 soldiers served. The inscriptions we dealt with date to a short period in the last phase of the life of the fortress, on the eve of the destruction of the Kingdom of Judah. Some of Arad's letters are addressed to 'Elyashiv ben Ashiyahu', the apsanai of the citadel. These correspondences are of a logistical nature and talk about the supply of flour, wine and oil to army units in the area. According to one thesis, among the soldiers, who could not read and write, sat one scribe who managed the records and correspondence for all the residents of the citadel. Another possibility is that the inscriptions were written by various officials in the citadel, who represent a broad literate population."

The algorithm compares the letters

"We decided to examine the question of literacy in an empirical way, from different directions of image processing and computational learning," Shaus says. "These are areas that, among other things, currently help in the identification and analysis of manuscripts, signatures, etc. The big challenge was adapting modern technologies to 2,600-year-old ostracans. After much effort, we managed to create an algorithm that knows how to compare letters and answer the question of whether two given ostracon were written by different hands."

"We examined 16 inscriptions, the longest of the Tel Arad inscriptions," says doctoral student Shira Feigenbaum-Golovin, "and we reached a high statistical certainty that the inscriptions were written by at least six different writers."

"If in 16 inscriptions found in a small peripheral outpost of 20-30 soldiers we find evidence of six literates, we can infer from this the degree of literacy of the entire society," Sober says. "This means that the commander of the fortress, the manager of the warehouse and even his lieutenant can read and write."

"In the Judea of the end of the First Temple there are those who will write, and there are those who will write," explains Prof. Pisecki. "We estimate from archaeological surveys that the kingdom of Judah at that time numbered about 100,000 people. Now we know that a significant number of them were literate. It is not, therefore, just a handful of writers who lived in Jerusalem and composed administrative and religious texts for limited use. The later kingdom of Judah was an organized state, probably with schools, teachers and a developed educational system for military and administrative personnel. It is a fact that even in military outposts such as Arad, Lachish and other peripheral sites, military orders were given in writing."

"The results of the study show that in a remote citadel in the Be'er Sheva Valley, writing was common," says Prof. Israel Finkelstein. "From the content of the letters, we learn that literacy has permeated the lower levels of the kingdom's military administration. If you extrapolate these data to other areas of Judea, and assume that this was also the case in the circles of the civil administration and among the priests, you get a considerable level of literacy. Such a level of literacy constitutes an adequate background for the composition of biblical texts".

9 תגובות

16 different writers, on a site with 40 people per unit of time.

When it is assumed that the pottery was written over a period of several hundred years... it turns out that it makes more sense that at any given time there were a small number of people who knew how to write

Let's say a period of 400 years, each person worked for 25 years, that's exactly 16 different people.

1. In my opinion, in order to get a proper perspective, it is necessary to check whether there was a parallel to such a finding in other cultures or whether the phenomenon distinguishes the Hebrews.

If this is unique, then there is in the discovery a great reinforcement of the explosiveness of the knowledge of the script among the Hebrews, as is hinted at in many places in Tanach, in a tendency to be silent as if it were a trivial matter....

2. The method by which they succeeded in discovering the writing was to examine any pottery that is the right size for writing and may have letters that the eye cannot see.

3. It is also important to recognize the "flow of writing on the clay" an orderly writing that is written lightly indicates the writing that is a routine act of the writer and has an additional facet to the very knowledge.

third. A previous study by Professor Israel Finkelstein dealt with minimizing the role of the House of David and I actually believed him. In the last 15 years, discoveries of tombstones have appeared throughout Israel that confirm the size of the House of David. For example in the Golan Heights. The king of Aram boasts that he cut down the house of David - corresponds to Athaliah's attempt to stop an Aramaic-Israeli invasion of Judah and killed the twins - the last remnant of the house of David. Research should be accurate. If this is what it is as facts then it is what it is. A hypothesis can be expressed but emphasize that it is a hypothesis.

There is a wrong assumption in the article. Even if the letters were written by 6 different people, this does not necessarily indicate the number of people who know how to write in the population. There may have been one role of a writer and every few years the writer ended his role and was replaced by another writer. So if you want to calculate the statistics, you have to calculate 6 writers from the general population and not from 40 people who served in the fortress.

Joseph

By and large you are right. But this research actually sounds convincing. 16 literate people in a place that held only 40 people. Such a finding cannot be ignored.

Obviously a chemist can afford more certainty. At any moment he can conduct an experiment and check. The historian does not have this ability.

In this context it is worth noting that according to sage tradition during the time of King Hezekiah - roughly corresponding to the period of the findings, all the people of Israel, even infants, were well versed in the many and complicated laws of impurity and purity. This testifies to considerable educational knowledge that can also come together with additional literacy skills. like writing

In ancient history and archeology there is a jumping to conclusions that a scientist in exact sciences, natural sciences would not allow himself. From the fact that a military governor and his deputies signed a document infers that they wrote it, and from the fact that they wrote it in Tel Arad infers that this is the practice in the rest of the country, and from the fact that the writing was widespread throughout the country. There is no proof of these skips. More precisely, if a military governor and his deputies are signed, they may have employed an official who knows how to write, and this does not indicate that they themselves know how to write. If anyone in Tel Arad knows how to write, this is an exemplary sample. Maybe in other places he doesn't know how to write and so on.

Just as a piece of wood was found that belongs according to hypothesis only (an important scientific tool) to a harp and therefore "perhaps King David's harp was found". wow

Really really not surprising. Revealing the origins of the people of the book.

The claim that only the priests were educated is a legend.

Explained in the Torah: (Deuteronomy XNUMX:XNUMX) And it would be if she did not find favor in his eyes because he found her a virgin and wrote her a book of circumcision and put it in her hand and sent her away from his home. And later: (Deuteronomy XNUMX:XNUMX) And the last man hated her and wrote her a book of circumcision and put it in her hand and sent her away from his home. The order for each person to expel is in writing, not orally as with the Muslims.

And all of them were specifically commanded (the emphasis is in asterisks) - (Deuteronomy Lev, from the Psalms) And Moses was able to speak all these things *to all Israel*: and he said to them, put in your hearts all the things that I have spoken It is a witness among you this day that you fast your sons to observe to do *all my words This Torah*: for it is not a mere word of yours, for it is your life, and by this word you shall prolong your days on the land where you cross the Jordan, which you put in its net:

If all of them did not know or at least most of them could read and write, it would not be possible for the team to keep the things religiously.

A really surprising find. I would not have thought that there would be so many literates.

I would expect a well-known among the priests.

But I don't think it's possible to say that a small fortress would happen to have 16 priests.

It is interesting to check additional periods with the same method.