The now complete decoding of the nematode worm's genome is an ideal exercise for the great battle over the human genome

It's not every day that the genome project gets a headline on the front page of Haaretz. Last Friday this happened, due to an achievement whose meaning is not easily understood even by those who trust the human genome and its consequences. Why were the news agencies alarmed at the announcement of "mapping all the genes of a roundworm"? Why did this justify a special issue of "Science", the most prestigious science newspaper in the world?

The Genome Project aims to decipher the genetic code of living beings. The project, in which billions are invested all over the world, heralds an unprecedented revolution in medicine, agriculture and biotechnology. One of his important goals is to decode the three billion DNA "letters" that make up the human genome. These describe in chemical language every detail of our body, from the number of fingers on the hand to the color of the hair, a tendency to diabetes to the folds of the brain. But can we learn a thing and a half about all these from studies dealing with a tiny worm?

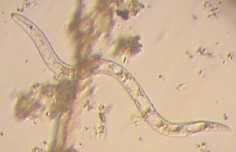

The nematode worm (Cynorbeditis elegans, a name that means elegant new worm) is one of the simplest and most inferior creatures living on earth today. C. elegans, as it is called for short, lives and reproduces to its fullest in the moist soil around us and preys on bacteria that are abundant there. The nematode is so tiny that at the point at the end of this sentence, five of its size can easily squirm. To her credit, about 600 million years ago she was the tiara of creation. In the billions of years before it, all creatures on earth were single-celled. At a certain moment, most critical in the course that eventually led to the development of man, the individual cells began to form colonies, and then formed orderly multicellular bodies such as the nematode.

This wonderful moment in the evolution of life can be likened to tasting the tree of knowledge.

The nematode was one of the first creatures to develop a nervous system, which eventually led to the emergence of consciousness. In return, the first multicellular creatures gave up eternal life: sexual reproduction appeared with the help of sperms and eggs, and with it - the inevitable death of the father and mother. The nematode represents an early stage in this process and is the hermaphrodite - male and female in one body. If the nematode was only a beautiful model for understanding the structure and early evolution of life, as the British scientist Sidney Brenner first stated, it is difficult to assume that tens of millions of dollars would have been invested in cracking its genetic text. One of the reasons for this massive investment was the recognition that deciphering the nematode genome would be an ideal "preliminary exercise" for the great battle over the human genome. Although a human is a billion times heavier than a worm, the nematode genome is only thirty times smaller than a human. In other words, the information density in units of bits per gram of weight is more than a million times greater in the tiny nematode compared to the current tiara of creation.

In fact, the nematode is even closer to man than one might guess just by comparing the lengths of their genetic texts. In nematodes, the information is more concentrated and the genome contains fewer "meaningless" sequences. Therefore, if we count the genes (the pieces of information that encode the units of protein structure and action) we will see that the human genome actually has only four to five times more useful information. Furthermore, there is a surprising match in gene types in nematodes and humans; The differences are summarized in sequence changes that do not change the function to a considerable extent. The similarity is also reflected in the fact that the worm has a basic body structure similar to that of higher creatures. Its thousand cells, each of which is almost indistinguishable from the trillions of cells in the human body, build a nervous system, senses, muscles, digestive organs and sexual organs. It is hypothesized that almost every human gene has a corresponding gene in a nematode, and that humans are allowed to have several versions of many types of genes at their disposal, which allowed great flexibility during evolution and the creation of complicated structures such as the human eye or brain.

Decoding the nematode genome took about ten years. At the beginning of the project, there were those who joked about the scientists heading it - John Selston from the Zenger Institute in England and Robert Waterston from Washington University in St. Louis in the United States - who chose to devote all their efforts to a tiny worm. But the smile was erased from the scoffers' faces during the decade. As the project progressed, the partial results obtained were examined in detail and the amazing similarity between the nematode and human genes was clarified. Many similar nematode genes have been discovered

Very similar to those whose defects cause human diseases such as cancer or Alzheimer's. Genes responsible for the worm's aging and social behavior were also discovered, and their counterparts may also be found in humans. In many cases, the study of genetic mutations in nematodes has made it possible to shed light on unknown functions of genes in humans. Thus it was made clear beyond any doubt that every dollar invested in the genetic letters of the worm generates great profits in the biotechnological and biomedical industries and contributes to human health and well-being.

In light of all this, one can understand the enormous significance of this scientific achievement. It should be emphasized that this is not a "mapping" of the 19 thousand genes in the nematode; This task was mostly completed years ago and is comparable to numbering the pages of an encyclopedia. The significant achievement is in reading the sequence (or "sequencing") of the complete genetic text - close to one hundred million letters or DNA bases. All information is available to the public, and can be received and analyzed via the Internet. This is the first time this has been done in a multicellular organism

any. The largest genome sequenced so far (about two years ago) is that of the single-celled yeast, and it has only 13 million letters. It is expected that with similar methods the sequencing of the human genome, with its three billion letters and approximately 80 thousand genes, will be completed within three to four years.

Based on the nematode genome, it will be possible for the first time to get an accurate picture of the infinitely complicated flow chart of a multicellular animal and of the way in which a single cell (also in humans) develops into an embryo and an adult being. This will require many more years of research, while using the best innovations in molecular genetics and bioinformatics (a subject that combines biology and computing). It will also be possible to understand man's place in the "tree of life" - the diagram describing evolution from the first bacteria to the present. It is true that we are intellectuals who study the nematode and enjoy its fruits, but deciphering the nematode genome also commands us to be humble before other life forms, even if they are the size of a pin head - a whole world is embodied in them.