The new planets still require further verification to be definitively defined as such. Of these, 10 are Earth-like orbiting their star at the appropriate distance where liquid water can exist. The researchers also noticed that among planets that are not gas giants, there is a clear gap that divides them into two distinct types: rocky planets, with a size of up to 1.75 the diameter of the Earth, and those that are slightly smaller than Neptune, and are called "mini-Neptunes".

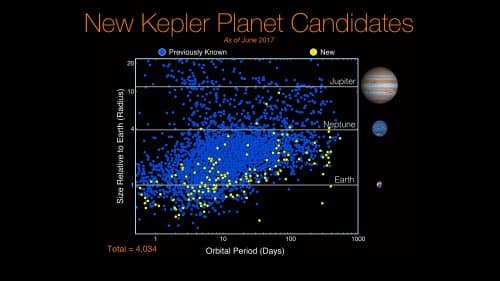

At a press conference held yesterday at NASA's Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, California, the space agency She announced About a new catalog of 4,034 extrasolar planet candidates discovered by the Kepler space telescope. Of these, 2,335 were definitely identified as planets, and the rest require further verification, to rule out the possibility that another factor affected the space telescope's measurements.

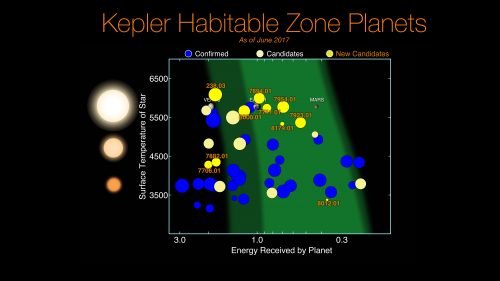

The new catalog, which is based on data collected by the telescope during its main mission (2009 – 2013), adds 219 planet candidates to those already known from previous catalogs. Of these, 10 planets are Earth-like that orbit their star inthe sitting area”, one that is at a distance from the star that allows liquid water to exist on the surface. Their location at the appropriate distance, however, does not guarantee that they actually have liquid water on them, as additional conditions, such as the existence of the right atmosphere, are required for this.

The ten new earth-like planets are added to another 40 that are similar to the earth in size and are in the yeshiva area. Of these 50 candidates, 30 have been confirmed with certainty as planets. These planets will be used by researchers in the future as foci to search for signs of life outside the Earth.

The planet most similar to Earth, among the new planets, is KOI 7711 (abbreviation of Kepler object of interest). Although its identification has not yet been definitively verified, the researchers said that its radius is only 1.3 times that of Earth, and it is in a similar orbit to that of Earth, around a star similar to our Sun.

The Kepler space telescope is the most fruitful mission so far in the search for extrasolar planets, and according to NASA researchers, 80% of all the extrasolar planets discovered were discovered by Kepler. The rest were discovered by other space telescopes and ground-based observatories.

Kepler detects extrasolar planets using “The eclipse method", an indirect detection method, in which the star's light intensity is measured with great precision. Dimming at regular and continuous time intervals indicates that some body - a planet - surrounds the star and hides some of its light.

According to NASA, the new catalog is the most comprehensive and detailed compiled from the raw data collected by Kepler. To check that no planets were missed, the researchers added artificial defects to the analysis of the data, and checked how many of them were identified as planets. In addition, to determine the reliability of the detection, they added to the analysis misleading data that resembled the eclipse of a planet, and checked how many times they were incorrectly identified as planets.

Planets that are similar to Earth not only in size, but also in the parent planet

About half of the ten newly discovered Earth-like planets orbit a star similar to our Sun (star MType G). In this way, the new catalog manages to close a little the gap created in previous catalogs of Kepler candidates, in which most of the Earth-like planets in the host region were discovered around Red dwarfs, stars much smaller than our sun.

Red dwarfs make up the vast majority of stars in the universe. Because their radiation intensity is weaker, their orbital region is much closer to them than that of stars like our Sun. On the one hand, this makes it easier for telescopes like Kepler to detect small Earth-sized planets around them, because the eclipse they create is stronger and occurs more frequently (due to the very short duration of the eclipse, which sometimes lasts only a few days). On the other hand, There are researchers who believe that being so close to the mother star decreases the chance that life could develop on them.

Some of the newly discovered planets, as mentioned, are similar to the Earth not only in size, but also in the mother star that they orbit. "This Kepler data set is unique, as it is the only one that contains a population of Earth analogues - planets that are roughly the same size and orbit as Earth," said Mario Perez, Kepler mission scientist.

"This catalog, carefully measured, is the basis for a direct answer to one of the most pressing questions in astronomy - how many planets like Earth exist in the galaxy?", added Susan Thompson, a scientist on the Kepler mission and the lead researcher on the team that prepared the catalog.

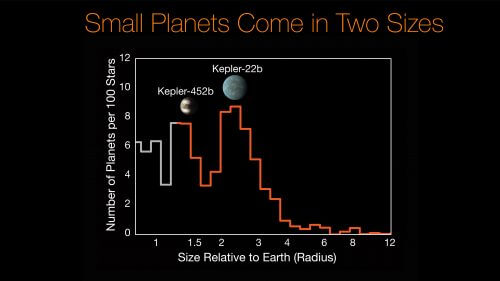

A clear gap between terrestrial planets and mini-Neptunes was discovered

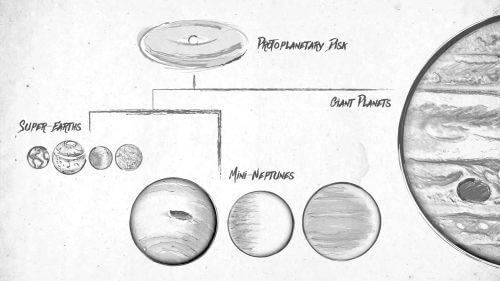

At the press conference held by NASA yesterday, the results of another study based on Kepler data were also announced. The new research He found that most of the planets that Kepler discovered are divided into two types of different sizes - terrestrial planets that are similar to the Earth in size, and those that are slightly smaller than the planet Neptune (which is 4 times the size of the Earth). Kepler discovered very few planets in the gap between the two groups.

"This is a new major division in the planetary family tree, which is similar in importance to the discovery that mammals and reptiles are separate branches on the tree of life," explained Andrew Howard, professor of astronomy at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), and the lead scientist of the study.

Astronomers have known until now, from Kepler's discoveries and other observations, that most planets that are not gas giants like Jupiter range in size between Earth and Neptune. But the exact size of the "smaller" planets was unknown, and researchers had trouble determining how they were distributed within this gap: how many planets were more like Neptune, and how many were more like Earth.

The new study attempted to answer this question by determining the exact size of about 2,000 extrasolar planets discovered by Kepler. The team of researchers from Caltech, along with other researchers from around the United States, used successive observations of Kek Observatory in Hawaii. By measuring the exact size of the planets' parent stars, the researchers were able to determine their size with an accuracy that is 4 times larger than previous measurements.

Thanks to the new measurements, the researchers noticed a clear gap within the group of smaller planets, and that they are divided into two distinct groups. One group is of rocky planets, with a diameter up to 1.75 that of Earth. The size of the planets in the second group ranges from 2 to 3.5 times that of the Earth. They were nicknamed "mini-Neptunes", due to being slightly smaller than Neptune, which is about 4 times the size of the Earth.

The researchers estimate that "mini-Neptunes" also have a dense and large atmosphere of hydrogen gas and helium, like Neptune and gas giants, but their mass is not much greater than the mass of the terrestrial planets. These mini-Neptunes are very common in the universe, although in our solar system there are no known planets that are larger than Earth and smaller than Neptune. It is possible that "Planet Nine", whose existence was proposed last year, suitable to be considered as such, but it has not yet been located and is considered only a hypothesis.

"In the solar system, there are no planets between the size of Earth and Neptune," said Eric Pettigora, co-author of the study from Caltech. "One of the biggest surprises from Kepler is that almost every planet has at least one planet that is larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. We really want to know what these mysterious planets look like, and why we don't see them in our solar system."

As mentioned, the researchers found very few planets whose size falls in the gap between the two groups, and they have two possible explanations for the phenomenon. One possibility is that most planets form initially with a size and mass similar to that of Earth. Some of them, for a reason that is still not entirely clear to researchers, accumulate enough gas during their formation, "jump across the gap" and become mini-Neptunes.

"With the exception of hydrogen and helium, there is a great deal of influence. Therefore, if a planet accumulates hydrogen and helium to the extent of XNUMX percent of its mass, that is enough to jump across the gap," said Howard. "These planets [mini-Neptunes], are like rocks with big balloons of gas around them. The hydrogen and helium in the balloons do not really contribute to the mass of the system as a whole, but they do contribute enormously to the volume, making the planets much larger."

The second possibility is that planets, which are formed in the gap between the two groups, do not stay that way for long. The researchers hypothesize that such planets lose their gas by being eroded by their star's radiation, gradually turning into terrestrial planets.

"It is unlikely that a planet would have the right amount of gas to fall into the gap. And the planets that do have enough gas may lose their thin atmosphere. Both scenarios probably cause the difference in the sizes of planets we observed," Howard explained.

The researchers' article will soon be published in The Astronomical Journal, But it can be read through the arxiv website.

Kepler is just the beginning

Kepler's new discoveries, both the 219 new planets and the gap between rocky planets and mini-Neptunes, are based on data from Kepler's first four years, between 2009 and 2013. During that period the telescope regularly observed a very small area of the sky, bSwan constellation. In 2013, a mechanical malfunction occurred in it which necessitated the interruption of the main mission. The mission managers managed to "save" the telescope and continued with a secondary mission known as K2, which is also looking for extrasolar planets.

But Kepler, which was one of the first space telescopes launched with the deliberate goal of searching for planets, is just the beginning. Besides the ground observations that are increasing year by year, in 2018 it will be launched into space TESS space telescope of NASA. TESS will be very similar to Kepler and will also use the eclipse method, but it will observe the entire sky and brighter stars similar to our sun. Another European Space Agency telescope named CHEOPS It will be launched at the end of next year, also giving up other planets.

In 2018 will also be launched James Webb Space Telescope, which will serve as a "successor" to the old Hubble Space Telescope. Webb, which will be the largest telescope ever launched into space, will be able to analyze the chemical composition of the atmospheres of extrasolar planets. In this way, researchers will try to locate signs of biological activity on distant planets, just as oxygen and methane in the Earth's atmosphere indicate the vibrant life that exists on it. NASA scientists are also planning more advanced missions, ones that will be able to hide the light of the stars around which the planets revolve, and observe them directly (such as The WFIRS space telescope).

See more on the subject on the science website:

- "Technological improvement in the field of spectroscopy made possible the wave of discoveries of planets outside the solar system"

- NASA Announces 1,284 New Extrasolar Planets - Largest Harvest to Date

- A system of seven Earth-like planets was discovered, three of them in the zone suitable for the existence of liquid water

- Planets for the most part - there is no life

- Is there life on the nearest planet, Proxima Centauri b?