Data from the malfunctioning space telescope reveals new worlds

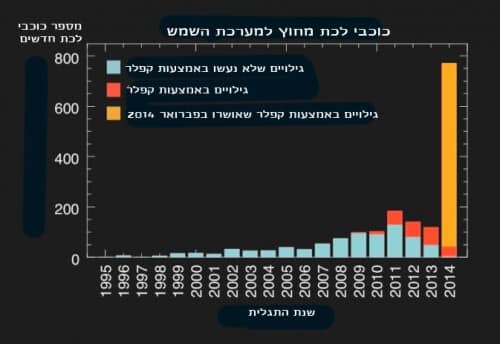

NASA's Kepler space telescope was launched in 2009 and stopped collecting data in 2013 due to a mechanical failure. However, in his relatively short life, he managed to accumulate a treasure of discoveries. In February 2014, scientists announced a new collection of findings that brought the total number of planets discovered by Kepler to nearly 1,700. "This is the biggest find yet," says Jason Rowe of NASA's Ames Research Institute, who co-led the study. The scientists studied more than 1,200 solar systems and confirmed the discoveries of 715 planets. All the new worlds are found in solar systems that have more than one planet.

The researchers used a new method to filter out false signals. Kepler searched for planets by measuring the brightness of stars and detecting decreases in light intensity that occur when planets pass by. This technique, known as the "transiting method", is very accurate. But sometimes a celestial object that is not a planet can fool the telescope. One of the common reasons for "false detection" are "eclipsing binaries" - a pair of holiday stars around each other and from time to time one of them passes by its partner as seen from the telescope's point of view.

Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between a star with a single planet and such a double system. In contrast, the chance of misidentifying multi-planet systems is much lower. "Sometimes it happens, but it's rare, that two double stars will be behind the same star," says François Persin, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Institute for Astrophysics, who was not involved in the study. It is also possible, though extremely unlikely, for a double malefic star and a planet-bearing star to be exactly above each other.

Rowe and his colleagues attempted to spot the false discoveries by examining the light coming from the possible planets. They looked for a certain characteristic pattern known as a "moving centroid": a change in the position of the center of light in the image received by the telescope, which indicates that the source of the fluctuations in brightness is most likely a double star located in the background and not a planet.

Among the observations that passed the screening was a planet that may be rocky, a strange binary system where each of the two stars has its own planet, and dense systems where the planets exert their gravitational influence on each other. "Our set of confirmed solar systems includes every type of planetary system imaginable, with the exception of a perfect counterpart to Earth," Rowe says. Such a discovery still remains Kepler's golden fleece.

The article was published with the permission of Scientific American Israel