Scientists from the Weizmann Institute discovered that nerve cells located in one of the nuclei of the hypothalamus, and expressing a receptor called CRFR1, help the body deal with exposure to chronic stress. These receptors are expressed as a result of exposure to the hormone cortisol, and are "activated" by the neurotransmitter CRF.

When humans are exposed to stressors - their body becomes agitated and reacts with over-arousal. This response allows them to deal optimally with the "threat" facing them. Since this threat is usually localized, the reaction to the stress factors also tends to be short-lived and gradually fades away. But what happens when the stressors do not go away by themselves, but come back and appear with high frequency? In a new study by scientists of the Weizmann Institute of Science, a brain mechanism was revealed that allows dealing with chronic exposure to stressors; the study Recently published In the scientific journal Nature Neuroscience.

"In one of the nuclei of the hypothalamus (an area of the brain involved in regulating many responses in the body, including the response to stress), called the PVN, we discovered a distinct population of nerve cells involved in the body's response to chronic stress. This population was not known until today," explains the post-doctoral researcher Dr. Assaf Ramot, who led the study. Dr. Ramot, who belongs to the laboratory of Prof. Alon Chen from the Department of Neurobiology, collaborated in research with the group of Dr. Nicholas Justice from the University of Texas. "We knew that it was a small population of nerve cells, and we wondered what exactly their role was. We hypothesized that, in light of their location in the hypothalamus, they play an important role in controlling the stress response," says Prof. Chen.

The scientists discovered that these nerve cells are part of the brain mechanism that helps deal with chronic exposure to stress - a mechanism that was not known until now. "In a routine reaction to stress, which is evolutionarily conserved in all vertebrates, a chain of actions is activated, the center of which is the activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis). This is the classic mechanism," explains Dr. Ramot. The beginning of the chain in the neurotransmitter CRF, which is released from the PVN nucleus in the hypothalamus and goes to the pituitary gland. Following this, the pituitary releases hormones into the blood, and these, in the end, cause the release of the "stress hormone" (cortisol in humans; corticosterone in rodents) from the adrenal gland. A process of "negative feedback" in this chain means that the response to stress gradually fades, as Prof. Chen explains: "The release of cortisol causes a reduction in the release of CRF, and this leads to the 'turning off' of the stress response and a return to regular cortisol levels."

However, the new mechanism discovered by the scientists is actually based on "positive feedback". In other words, the stress hormones cause the mechanism to start, not to turn it off. "Since this mechanism activates the stress response, while the classic mechanism 'turns it off', it is a sort of 'compensating mechanism'," says Prof. Chen. "For this reason, we called it 'control of control.' This is a hidden mechanism that helps the body deal with chronic stress."

The neurons that the scientists discovered express the type 1 receptor for CRF (which is CRFR1). This receptor enables communication with the neurotransmitter CRF, which "triggers" the body's response to stress. "In the experiments we performed on mice, it became clear that corticosterone is responsible for the amount of receptors. That is, its circulation in the body causes them to be expressed in the PVN nucleus, where the same nerve cells that release CRF are also found", explains Dr. Ramot. Prof. Chen adds: "When the stressors multiply - that is, when it comes to chronic stress - the CRF, which is located near the receptors, is the one that activates them. This is the key that causes them to take action."

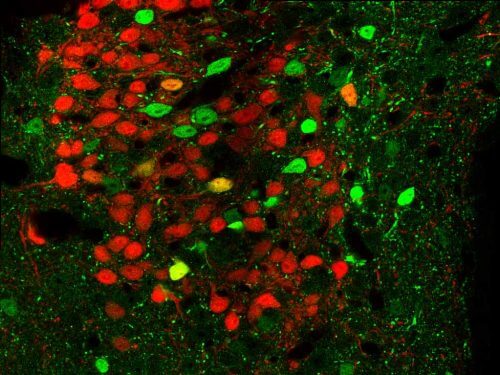

The research findings were obtained following experiments conducted in several stages. In the first step, to establish the characteristics of the nerve cell population that expresses the CRFR1 receptor, the scientists studied mice that were genetically engineered to express a fluorescent marker in this population. The genetic engineering procedure in mice was carried out by their research partner, Dr. Justice. "When we looked at the nerve cells under the microscope, we realized that they are a distinct population in the PVN nucleus," explains Dr. Ramot. "In this nucleus there are many hormones and neurotransmitters, but the neurons that express the CRFR1 receptor do not overlap with any other known population. They are a group that stands on its own."

In a second step, the scientists removed the adrenal gland in a similar group of genetically modified mice - so that they could not release stress hormones (corticosterone). In doing so, they sought to examine the relationship between the release of corticosterone and the response of the receptors to it. "We looked at the brains of the mice with a fluorescent microscope, and we saw that the expression of the receptors disappeared completely. But when we injected them with synthetic stress hormones, we saw that the receptors reappeared. This is how we showed that there is another pressure control mechanism in the body, based on positive feedback." Later, in collaboration with Dr. Justice's research group, the scientists conducted an electrical recording for those fluorescently labeled nerve cells. "And then we saw that when the CRF hormone is released in the PVN, the marked neurons go into action."

In the last step, the scientists compared two groups of mice - mice that were genetically modified so that the CRFR1 receptor is not expressed in them (in the PVN nucleus), and normal mice. They gave both groups different anxiety tests, and then tested the amount of stress hormones in their blood. The researchers found that the behavior of the mice without the receptor was the same as that of the normal mice. However, when both groups of mice were exposed to chronic stress, the genetically engineered mice exhibited less anxious behavior, and their bodies released less stress hormones, compared to the normal mice. "From this we concluded", says Dr. Ramot, "that the control mechanism we located is activated in a situation of continuous exposure to stressors. In a situation of point pressure, there is no difference between the two groups of mice, since the classical mechanism is expressed in both. But in a situation of chronic stress, the group of Hebrews lacking the receptor releases less stress hormones. It is possible, among other things, that this is due to the fact that the classical mechanism leads to a decline in response to anxiety. However, it is not yet completely clear to us how the receptors are involved in the process, and there is room to examine this in further research." Prof. Chen adds: "The nerve cells we identified are responsible for the response to stress being maintained even in a state of chronic stress. In other words, they allow the body to deal with repeated exposure to stressors."

Since past studies have shown that more CRFR1 receptors are found in depressed patients compared to the control group, the scientists believe there is now room to examine whether these receptors may also contribute to the hormonal aspect of depression. "In addition, it is possible that with the help of the nerve cells and the mechanism we uncovered, a way will be found to treat people suffering from chronic stress," say Prof. Chen and Dr. Ramot.

#Science_Numbers

In a study conducted in England, it was found that stress related to the workplace means that, on average, an employee loses 24 working days a year.