Prof. Uriel Bacharach reveals in a new book unknown heroic stories of young Israeli scientists during the founding of the state. Surprising revelations about biological warfare and the true roots of the Israeli nuclear program. Coincidentally, Efraim Katzir, who was one of the founders of Hamad and commanded it in its early years, passed away recently.

On the second of February, 1948, about three months before the establishment of the state, Aharon Katzir convened a group of students from the Hebrew University. "The people of Israel are in danger," he told them, "Arab countries are about to invade our country. We have no weapons and infrastructure. The eyes of all Israel are on you."

David Ben-Gurion was the driving force behind the establishment of the Science Corps. He turned to Aharon Katzir, a world-renowned scientist, and asked him to recruit the best young minds for the development of technologies and weapons. Aharon agreed, and later Ben-Gurion also managed to convince Efraim Katzir, Aharon's brother, to leave the United States and return to Israel to command the Science Corps. Ben-Gurion greatly appreciated the Jewish scientists and their abilities. In one of the first meetings of the First Knesset he said: "There is no nation in the world that surpasses us in its intellectual virtues. We are not behind in the field of research and science. There is no reason for the scientific genius to flourish and prosper in his native land less than in foreign countries."

But the scientists and researchers of the Science Corps were only third-year students - and there were no military chemistry lecturers in Israel. There was no one to teach them how to mix explosives. There was no teacher to explain how an anti-tank shell works. Nowadays it is hard to imagine a situation where young and inexperienced students are allowed to develop weapons and explosives. To be honest, I find it hard to believe that even then anyone believed that anything of value came out of it. But the inexperienced students had one significant advantage - they were inexperienced, and no one explained to them that what they were trying to do was, in principle, impossible. So they succeeded.

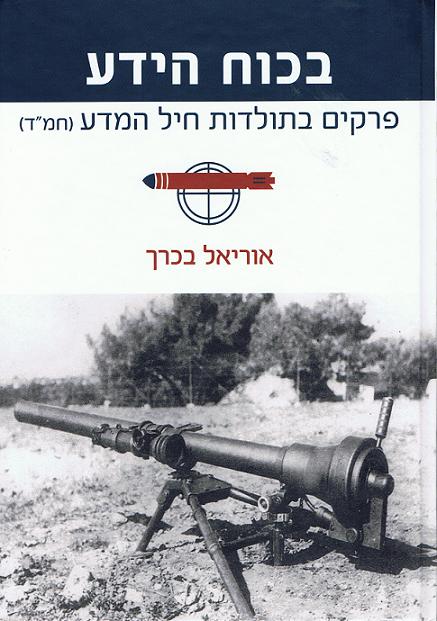

About two months ago, the book 'In the Power of Knowledge: Chapters in the History of the Science Corps', penned by Prof. Uriel Bacharach, currently from the Department of Molecular Biology at the Jerusalem School of Medicine, was published. In this book, for the first time, the amazing stories and secret heroic plots of the young scientists who founded the Science Corps are brought together. This corps, of which Uriel was one of the founders, became over the years the foundation on which all our defense industries were built.

The total amount of professional knowledge at the disposal of the Science Corps officers was one book on military chemistry that was borrowed from the library. In the morning one of the students would give a lecture on material taken from the book, and in the afternoon they would all go into the laboratory and try to put into practice what they had learned that morning. After that, Uriel and others were sent to a short sabotage course, and from there straight to the field. They developed grenades, mines, incendiary bombs and mortars and all under urgent conditions and a demanding schedule - because the Arab armies would not delay their invasion.

One of the inevitable results of the lack of experience was an extremely high rate of accidents. Many of the pioneers of the Hamad lost their lives on the laboratory table. Emanuel Midev, for example, was a young man who invented a substitute for a landmine - a hand grenade without a trigger that was placed inside a tin can, to which a wire was attached: when the enemy stepped on the wire, the grenade would be pulled out of the box and explode. In one of their experiments, Emanuel chose a box that was too big. The grenade exploded and he was killed on the spot. Uriel Bacharach himself was injured when he tried to test an incendiary bomb, and suffered burns on his hands.

One of the interesting and intriguing characters mentioned in the book is the character of Emmanuel Miron. Miron was deaf and mute - but it was his disability that pushed him to be interested in everything related to explosives: he liked to feel the shocks caused by the explosion. He sat together with all the others and studied from the books and notebooks, and then he was asked to set up a factory for the production of explosives. The friends were afraid that an explosive would fall on the floor and Miron would accidentally step on it: even so, he would be completely scarred as a result of his great love for unstable substances. The solution found was a dog that accompanied Miron in his work, and was trained to pull his pants every time an explosive fell on the floor. The bomb factory was a great success.

There was another interesting innovation in the nature of the Science Corps' operations. Almost all the students, it should be remembered, were Haganah, Palmach and Etzel fighters and had combat experience. Uriel was also a graduate of the Haganah's radar course, and before joining the Hamad he fought in the battles for the defense of Jerusalem.

This fact, combined with the time pressure that dictated a quick transition from the drawing board to the battlefield, led the Science Corps to establish units of 'warrior scientists': people who would operate the tools they designed in the field. There was no parallel for this in any army in the world: everywhere, including in modern Israel, the separation between the inventor and the soldier who actually uses his invention is maintained. In 1948 things worked differently. In the battle of the Yoav Citadel, for example, Zvi Shelah participated - a Hamed man who designed and built a heavy mortar. He used his invention in battle and thus helped a lot to capture the Egyptian outpost. Some time later he was seriously injured and lost his eye when another weapon was used - testimony to the many dangers of this type of activity.

There were senior officials in the military system who did not believe so much in the Jewish mind. In later years, when the scientists tried to initiate the development of a new missile, Chief of Staff Leskov asked them: "Why do you think you can make missiles. Have you ever done it?" To this, one of the researchers replied to him - "Why do you think you can be Chief of Staff?" Have you ever been?" Ephraim Katzir, who, as mentioned, commanded the Science Corps and later was the president of the country, says that in one of the demonstrations designed to test the effectiveness of the missiles, he saw Ezer Weizman hiding behind the target. to the question 'What are you doing there?' Ezer answered - "This is the safest place. They will certainly not hit the target."

But the officers in the field, says Uriel, knew how to appreciate the young scientists. When they encountered difficulties, they would turn to the Science Corps and ask for creative technological solutions. Even if they did not agree to a solution, they never rejected it with disdain.

One of the most fascinating revelations in the book is the story of the geological expedition to the Negev, which went out to look for oil and phosphates - and returned with the first seeds of the Israeli nuclear program.

According to a familiar British model, the Science Corps is divided into three units: A (chemistry), B (biology - more details below) and C - which initially stood for 'geology' but soon changed its role. In March 1949, a number of geologists from various universities went beyond the border line to explore the Negev and its treasures. They were accompanied by drivers and supply men, as well as Uriel Bacharach who was responsible for the defensive miking of the camp and breaking through dense wadis using explosives. The members of the delegation posed as German engineers who had come to examine a future route for the construction of a railroad. It is not clear if the costume was the one that convinced the Bedouins not to bother them, or maybe the cigarettes that the researchers bribed them with - but the operation went smoothly, and that is what is important. The rocks they brought with them from the journey were taken to a laboratory for testing, where a small but significant content of uranium was discovered. This uranium, according to foreign publications, is the same material from which the first two Israeli atomic bombs were built.

There were also less pleasant sides to the work of the Science Corps. Impressive technological developments in a short time and on a tiny budget - these are things you can be proud of. Using biological weapons, however, is in the gray area between pride and morality. The development of biological weapons, unlike atomic ones, does not require expensive resources. From reports that Uriel provides in the book, it appears that there is a reasonable possibility that our forces were responsible for poisoning wells in various Arab villages, as well as for spreading an epidemic in the city of Acre shortly before its conquest. From our point of view, sixty years later, things are not pleasant to the ear - but Uriel emphasizes that the weapon in question was not lethal, but was intended only to weaken the enemy.

The Israel Science Corps ended its duties in 1952, and was transferred to a civilian format under the supervision of the Ministry of Defense. From there it evolved and became the 'Military Development Authority' (Raphael), and its graduates were the main ones responsible for the current technological strength of the State of Israel. And not only with cannons and bombs, the Hamad helped the State of Israel: many of its people later continued in academic research careers at the various universities. The mental courage, the fresh spirit and the belief that the impossible is possible if you only want it - the mindsets that were rooted in the turbulent days of the young science corps - shaped the character of the Israeli academy and pushed it to its impressive achievements today.

Although 'By the Power of Knowledge' is not a book that excels in a clear and easy-to-understand chronological order or an excess of polished editing, its importance in revealing the work of these unknown heroes is invaluable. Many of the characters that appear in it have already passed away with a good return, and the memory of others is steadily fading. 'By the power of knowledge' is an impressive attempt - and perhaps the last of its kind - to shed light on some of the most hidden secrets of the State of Israel.

Editor's note

The book was published by a private publisher - N.D.D. media and it is not for sale in bookstores. It can be obtained at the publisher: 03-6040407

[The article is taken from the programMaking history!', a bi-weekly podcast about science, technology and history.

More on the subject on the science website

2 תגובות

as usual,

Excellent column.

Ran, nice list.

charming

Thanks