Dr. Eran Alinev Alinev explains: "In a study conducted using mice, we showed that after losing weight, the gut bacteria of the mouse retain a 'memory' of its obesity cycles. This memory accelerates the repeated weight gain when these mice return to eating high-calorie food or normal food in large quantities."

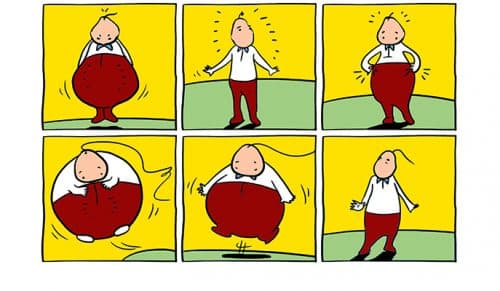

It is known that after a diet, the weight of many people returns and increases, a phenomenon known as "recurring obesity" or the "yo-yo effect". But it turns out that this phenomenon is accompanied by an even more serious mechanism: in many cases, with each return to excess weight, the weight increases beyond the excess weight of the previous obesity cycle. In addition, with each repetition, the percentage of fat in the body increases, and at the same time the risk of getting diseases related to excess weight, such as adult diabetes, fatty liver, and the other components of metabolic syndrome, increases.

As recently reported in the scientific journal Nature, scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science discovered that the mechanism of repeated obesity is significantly affected by the gut bacteria, and it is possible to change it by interfering with the composition and function of the gut bacteria population. The research was carried out by members of the research groups of Dr. Eran Alinev from the Department of Immunology, and Prof. Eran Segal from the Department of Computer Science and Applied Mathematics at the Weizmann Institute of Science.

Dr. Alinev explains: "In a study conducted using mice, we showed that after losing weight, the intestinal bacteria of the mouse retain a 'memory' of its obesity incarnations. This memory accelerates the repeated weight gain when these mice return to eating high-calorie food or regular food in large quantities." Prof. Segal adds: "Through a functional study of the intestinal bacteria, we deciphered the bacteria's contribution to the increased weight gain following successful weight reduction, and we developed diagnostic and therapeutic methods to treat the phenomenon."

Indeed, in an in-depth analysis of the composition and function of the intestinal bacteria, the scientists found that when mice gained weight and then lost back to their normal base weight, all their body systems returned to normal function, except for the active composition of the bacteria in the intestines and their mode of activity. For about half a year after the obesity and the successful weight loss, the mice maintained the abnormal intestinal bacteria pattern, typical of the "fat mouse".

Christoph Theiss, a PhD research student in Dr. Alinev's lab, led the research. He collaborated with the master's degree research student, Shlomik Yatev from Dr. Alinev's laboratory, with the PhD research student, Dafna Rothschild from Prof. Segal's laboratory, and with other scientists from the institute and other research institutions in Israel. In a series of experiments, the scientists showed that the "fat bacterial pattern" in mice that were successfully fattened and slimmed down is the one that accelerates the repeated obesity in these mice. For example, when the researchers eliminated the gut bacteria in mice with a history of obesity using broad-spectrum antibiotics, the accelerated reoccurrence of obesity was prevented. When gut bacteria, taken from mice with a history of obesity, were transplanted into mice with no gut bacteria, the mice that had the bacteria implanted in their bodies developed excessive obesity when fed a high-calorie diet, compared to transplanted mice that carried gut bacteria from mice with no history of obesity.

Later, using machine learning software they developed, the scientists were able to accurately predict, based on hundreds of characteristics of the gut bacteria, the rate of weight gain expected for each mouse with a history of obesity, under conditions of repeated overeating. By combining genomic and metabolomic approaches, they identified a mechanism by which the intestinal bacteria influence the rate of recurrent obesity. This mechanism is mediated through two molecules that originate from plant food, from the flavonoid family. The intestinal bacteria of mice with a history of obesity broke down these molecules faster, so their level in these mice was significantly lower compared to their level in mice without a history of obesity. The scientists discovered that these two molecules encourage the production of energy from the breakdown of fat tissue. The low level of the molecules in mice with a history of obesity inhibited the energy output from fat, so that excess fat remained and accumulated in their bodies when the mice were exposed to a high-calorie diet.

Finally, the scientists developed new approaches to prevent accelerated re-obesity in mice by altering the composition and function of their gut bacteria. Transplantation of naïve bacteria ("fecal transplant") into mice after successful weight reduction mimicked the bacterial "obesity memory", and prevented accelerated reoccurrence of obesity when the mice were again fed a high-calorie diet. Another approach to prevent recurrent obesity, which may be more suitable for use in humans, involved re-administration of the two missing flavonoid molecules into mice that had a history of obesity. Correcting the level of the molecules prevented the disturbance in energy output and the associated accelerated obesity in the treated mice. "We call this approach 'post-biotic'," says Prof. Segal. "Unlike 'probiotics', which involves the introduction of beneficial bacteria into the intestines, here we do not introduce the bacteria themselves, but the substances that these bacteria affect. This approach may be more effective than treatment using the bacteria themselves.'

As for the "yo-yo syndrome", this is a major problem, in every way. "Obesity currently characterizes half of the world's population," says Prof. Alinev, "and its complications cause mass morbidity and mortality due to diseases such as diabetes, fatty liver and heart disease. If it is found that the results of the research we performed in mice are also valid in humans, it may be possible to use them to diagnose and treat the recurring obesity epidemic."

Also participating in the study were Mariska Meyar, Maayan Levy, Claudia Morsi, Lenka Dohanlova, Sofia Braverman, Shahar Rosin, Dr. Mali Bakhsh, and faculty scientist Dr. Hagit Shapira, from the Department of Immunology; Faculty scientists Dr. Yael Koperman and Dr. Inbal Biton, and Prof. Alon Hermlin, from the Department of Veterinary Resources; and Dr. Sergey Malitsky and Prof. Assaf Aharoni from the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences from the Weizmann Institute of Science; as well as Prof. Aryeh Gertler from the Hebrew University, Rehovot Campus, and Prof. Zamir Halpern, from the Souraski Tel Aviv Medical Center.

2 תגובות

Greetings. I participated in the study and did not receive any further instructions. Thank you for instructions as a result of my participation in the study. Thanks. breakup

Intestinal bacteria have been present in humans throughout evolution...

Obesity is a characteristic of the last thirty years.

How is it that only now are the gut bacteria affecting human obesity?

A dubious, trendy theory, the falsity of which will become clear in a few years...