The fate of Canada's bituminous sands mines, and the world's climate, may depend on the Keystone XL oil pipeline

The red alarm lights flash, but Ben Johnson ignores them. Watching over a counter along which computer monitors are installed, the tall, thin and haunted engineer describes life in the bituminous sands mines (also known as "tar sands") of the province of Alberta, Canada. Johnson's job is to take the muddy mixture of ore and water and separate from it the bitumen, a semi-solid, tar-like crude oil that can be distilled into crude oil in its familiar form. Johnson and his two colleagues man a monitoring station located near the base of a cone-shaped structure as tall as a three-story building. The muddy mixture is pumped together with hot water into the center of the structure, which is shaped like an inverted funnel. The bitumen floats up, to the top of the building, and slides on top of the surrounding trellis.

In the 2012 incident, the bitumen bubbled upwards at such a high speed that it slid down the sides of the cone and flooded the building knee-high. To prevent such incidents, sensors were installed that monitor temperatures, pressures and other variables, and if something is not right, an alarm sounds. But it happens far too often: "1,000 alarms a day," says Johnson, so engineers usually silence the alarm sound. "The 'bing, bing, bing' is neutralized," Johnson explains, "otherwise we'd go crazy."

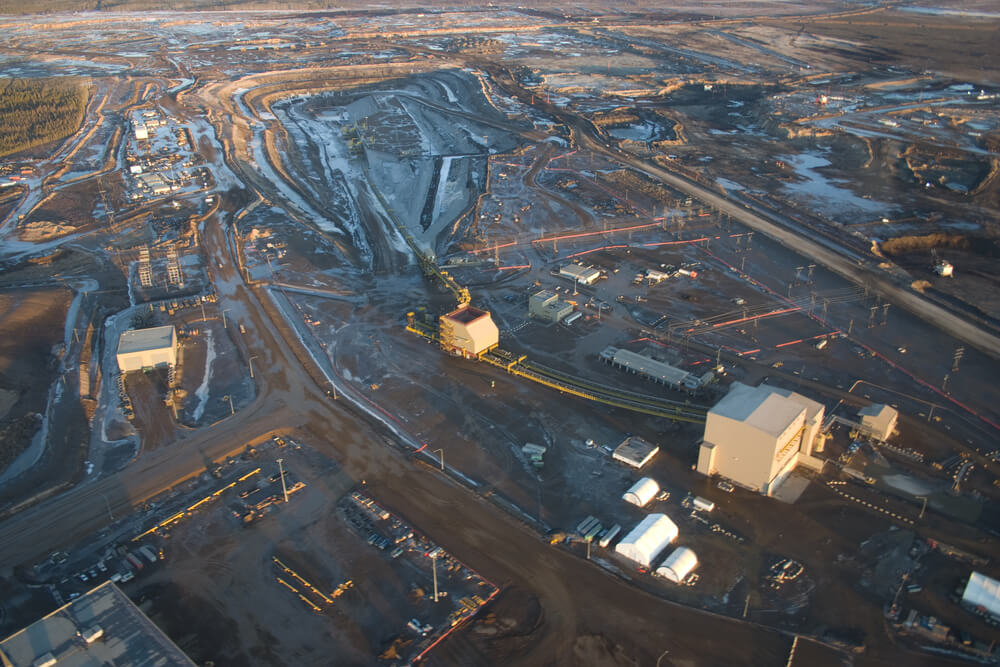

Suncor Energy's North Steepbank mine, where Johnson operates one of the many "separation cells", provides only a tiny fraction of the output of Alberta's bituminous sands deposits, which extend underground over an area the size of the state of Florida. Rising oil prices over the past decade have made mining these sands a profitable business, and Canada has rushed to expand production. In 2012 alone, the province of Alberta exported oil worth more than 55 billion dollars, mainly to the USA. No wonder, then, that Johnson and his staff have no free time to mess with alarms.

More on the subject on the science website

- Alberta's oil sands - the blessing and the curse

- The real cost of fossil fuels

- which extracts oil from the sand

However, the rush to the black gold hidden in Alberta's tar sands deposits is setting off alarm bells of a different kind: the bells of climate scientists. Emissions of carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels are rapidly bringing the world closer to the critical threshold of greenhouse gases: an atmospheric concentration of 450 parts per million, equivalent to global warming of two degrees Celsius or more. Beyond this threshold, scientists fear, climate change could be a disaster. While coal is a larger source of fossil carbon, mining and refining Alberta's sands requires more energy than is needed to produce conventional oil, with the result that more greenhouse gas emissions accompany the process. Moreover, the activity in the field of tar sands is growing at an accelerated rate, much faster than in most other oil sources in the world. The emission into the atmosphere of the carbon trapped in the bituminous sands will probably shatter any hope that we will be able to avoid the threshold of two degrees Celsius.

It seems that the fate of Alberta's tar sands, and indeed, of the world's climate, now depends on a planned project called the Keystone XL line. This oil pipeline, which starts in the province of Alberta and ends at refineries in Texas, along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, is intended to be the main line for the transportation of crude oil extracted from the tar sands. For ten years and even more, supporters of the factories in Alberta claim that the tar sands serve as a vital source of oil for the USA, because they are not affected by the political upheavals in the Middle East and other regions of the world. All that is required is a means of transporting the crude oil from the tar sands of Canada to the places where it will be used in the US and beyond, in Europe and Asia. And if it is not possible to build a pipeline such as Keystone XL, the oil will be transported in other ways, through another pipeline or by rail. However, in the opinion of independent experts, the construction of the Keystone XL line is essential to the continued growth of Alberta's tar sands industry.

But this information was not brought to the public's attention, when during the campaign for his re-election to the US presidency, President Barack Obama suspended the decision on whether to build the Keystone XL oil pipeline line. And when the issue comes up for discussion again, much more will be at stake.

The trillion ton threshold

At the vantage point overlooking the Suncor mine, exposed to the freezing cold of a northern Alberta winter, it's hard for me to avoid thinking that I could do quite well with a little global warming. The mine extends over a large area that has been prepared for the oil production industry in the heart of the taiga, the coniferous forest area of the sub-Arctic region, about 30 km north of Fort McMurray, a small town that suddenly became a prosperous city where the rental prices soared to the prices accepted in Manhattan and the truck drivers She earns $100,000 a year.

On the winding gravel road below the observation point, a convoy of the largest trucks in the world, a Caterpillar 797F model, passes, each of them carrying a compressed load of bituminous sand weighing 400 tons. (There is a huge demand locally for women drivers because they are more relaxed behind the wheel, but the supply is far from meeting the demand, as the number of men in the city is three times greater than the number of women.) The trucks move back and forth between huge electric excavators and Johnson's separation facility, and each round This one takes 40 minutes.

The trucks unload the ore into an industrial mill about the size of a small family car, which feeds the ground ore onto an oversized conveyor belt, which transports the tar sands to the separation chamber overseen by Johnson and his colleagues. A lump of ore just unloaded from the truck can be turned into separated bitumen in just 30 minutes. The black and sticky bitumen separated from the pulp rises as foam from the top of the separation chamber, is collected, and flows down a pipe to a refinery, where carbon is removed from it at a high temperature, and a thick hydrocarbon mixture similar to crude oil is obtained. In another method, the bitumen is mixed with lighter hydrocarbons in huge, wide and low storage tanks. The diluted bitumen mixture is liquid enough to be able to flow long distances through pipelines such as Keystone XL to refineries in the US.

The North Stepbank mine is only a small part of the first tar sands mine in the world, and is only one of the extensive mine system of the Suncor company, which together produce more than 300,000 barrels of oil per day. The company's holdings make up about 30% of the total output of the oil mines in the tar sands of Alberta, which is approaching two million barrels per day. This output is equivalent to that of more than 80,000 oil wells, an amount capable of meeting 5% of the oil demand in the US. The mines, with their vast lakes of toxic waste water and the bright yellow lumps of sulfur that have accumulated in them, are already so large that they are seen from outer space as a destructive industrial blob steadily spreading across the taiga region.

However, the invisible environmental impact of these mines may present us with the most difficult challenge of all. In order to pause the race towards the warming threshold of two degrees Celsius, humanity must take into account a factor known by scientists as the carbon budget: the total maximum amount of carbon emissions, estimated at one trillion (one thousand billion) tons, which must not be exceeded.

The concept of the carbon budget was coined by physicist Miles Allen from the University of Oxford during a study he conducted with six other scientists. In 2009, the research team collected observational findings on global warming and analyzed them using computer models of future climate change. The models were able to explain, among other things, the fact that carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere and continues to trap heat for hundreds of years. The permissible carbon budget framework of one trillion tons that they defined in their study determines the maximum amount of carbon that human activity can release into the atmosphere between now and the year 2050 without crossing the critical threshold of global warming. The pace of our progress towards the permitted emission limit is not important, what is important is that we do not exceed it. "The amount of carbon is the key variable here," claims James E. Hansen, a retired NASA climatologist who has been warning about climate change since 1988 and was recently arrested during protests against the Keystone XL oil pipeline. "It doesn't matter so much at what rate we burn it."

The source of the carbon emissions is also irrelevant. There is a fixed amount of carbon-based fuels that humanity can burn, whatever their source: tar sands, coal, natural gas, wood or any other source of greenhouse gas emissions. "From the point of view of the climate system, a molecule of CO2 is a CO molecule2, if it's from coal and if it's from natural gas," says Ken Caldeira, an expert in climate modeling from the Department of Global Ecology at the Carnegie Institution for Science at Stanford University.

According to Allen, to date, 570 billion tons of carbon have been released into the atmosphere as a result of fossil fuel burning, deforestation and other activities. Of these, more than 250 billion tons of CO2 [which are 68 billion tons of carbon] emitted since the year 2000 alone.

Today, an amount of approximately 35 billion tons of CO is emitted into the atmosphere every year2 (9.5 billion tons of carbon) due to human activity, and this amount is steadily increasing with the development of the global economy. According to Allen's calculations, at this rate, humanity will emit the trillionth ton of carbon into the atmosphere sometime during the summer of 2041. To stay within the carbon budget, we must reduce emissions by 2.5% per year, starting right now.

Underground treasure

In the tar sands of Alberta lie huge deposits of carbon, the remains of countless algae and other microscopic creatures that lived hundreds of millions of years ago in the warm waters of a shallow sea that covered a large part of the North American continent, assimilating carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in the process of photosynthesis. With the technological means available to us today, it is possible to extract approximately 170 billion barrels of oil from the tar sands of Alberta, which will emit about 25 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere in the process of burning the oil. An additional amount of 1.63 trillion barrels of oil - the burning of which will emit an additional 250 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere - will be possible to produce when the engineering way to separate all the bitumen from the tar sands is found. "If we burn all the oil stored in the tar sands, the temperature will rise, as a result of this burning alone, at a rate of about half the temperature increase we have seen so far," that is, it is a global warming of approximately 0.4 degrees Celsius, says John P. Abraham, an engineer Machines from the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

In surface mining, it is possible to reach deposits lying at a depth of up to 80 meters, but these make up only 20% of the tar sands. In many places, the tar sands deposits lie hundreds of meters below the surface of the ground, and the energy companies have developed a method for producing the bitumen in the field directly from these deposits, in a process of melting.

Using this method, in 2012 Cenobus Energy produced more than 64,000 barrels of underground bitumen per day at a mining site near Christina Lake in Alberta. Another one of the temporary camps that recently sprung up following the boom in the tar sands industry was established there. Clouds of steam rise from the nine industrial heating boilers standing on the site. With the energy produced from burning natural gas, treated water is boiled in these boilers, which turns into steam at a temperature of 350 degrees Celsius. In a control room even larger than the Suncor company's, Snobus employees flow the steam under pressure into the depths of the earth to melt the bitumen, which is then suctioned to the surface through a well and from there transported in pipes for further processing. Greg Feenan, operations manager at the Christina Lake site, likens the entire site to a huge water processing facility "which, by the way, also produces oil." In occasional eruptions, steam mixed with semi-molten tar sands is shot upwards, as happened in the summer of 2010 at a Devon Energy site where too much pressure was used.

At the Christina Lake site, engineers are injecting under pressure about two barrels of steam to pump back one barrel of bitumen. The process of melting the bitumen, due to the huge amounts of steam required for this and the natural gas that must be burned to turn the water into steam, involves the emission of greenhouse gases on the order of two and a half times more than the emission of polluting gases in surface mining, which is also one of the largest sources of environmental pollution in the extraction industry the oil. According to the Canadian Association of Petroleum Companies, there has been a 16% increase in greenhouse gas emissions from Alberta's tar sands since 2009 alone, following the increase in oil production using this smelting method. In 2012, for the first time, the volume of underground production of tar sands in Alberta equaled that of surface mining, and thanks to the expansion of activity at sites such as Christina Lake, underground mining is expected to soon become the main production method in the region.

However, the on-site production method is only effective when the bitumen lies at a depth of 200 meters or more, which leaves a gap of approximately 120 meters, where the bitumen deposits lie too deep to allow surface mining and too close to the surface to allow extraction by melting. So far, the engineers have not found a way to utilize the bitumen deposits lying between 80 and 200 meters deep, so the scenario of burning all the fuel stored in the tar sands deposits is not expected to materialize in the foreseeable future.

In any case, burning a significant portion of the oil stored in the tar sands is enough to bring the planet giant steps closer to breaking the carbon budget framework. To avoid this, we must stop burning coal or other mineral fuel, or, alternatively, find a way to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the tar sands. And it does not seem that any of these options have a reasonable chance of being realized. "Since 1990, emissions from the tar sands have doubled and will double again by 2020," says Jennifer Grant, director of tar sands research at the Pembina Institute, a Canadian environmental protection organization.

The keystone knot

The carbon budget is the factor that motivated Abraham, Caldeira and Hansen, along with 15 other scientists, to sign a letter to President Obama demanding that he reject the proposal to build the Keystone XL oil pipeline line, which is planned to be spread over 2,700 kilometers. The construction of this pipeline, which will allow further expansion of oil production from the tar sands, "contradicts both the national interests of the United States and the interests of the planet," the scientists wrote.

Obama, who delayed the decision to approve the pipeline just before the 2012 presidential election, took a climate-friendly stance in both his second inaugural address and his 2013 State of the Nation address to Congress. Obama will make the decision regarding Keystone XL after the State Department publishes its final report on the matter.

In the first draft of the report, the State Department claimed that the oil pipeline would not significantly affect the fate of the tar sands plants nor the environment. Keystone XL, the report said, "is not expected to have a significant effect" on greenhouse gas emissions. But the authors of the report seem to have assumed that if the line is not built, Canada will find another cost-effective way to transport the oil to consumers.

The response of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), published in April 2012, presents the issue in a different light. According to Cynthia Giles, deputy director of the EPA's Office of Enforcement and Oversight, the State Department report relies on flawed economic models and ignores other factors. Based on the experience gained in large-scale environmental assessments, the EPA says that the alternatives to Keystone XL are much more expensive or highly objectionable. In other words, without Keystone XL, the development momentum in the tar sands may come to a halt. Support for this analysis was provided by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in a May 2012 paper on the future of the tar sands.

Already today, the oil extracted from the tar sands is transported south by train, but this is only a temporary replacement. At today's rates, the cost of transporting oil by rail is three times higher than the cost of transporting it through pipelines. With the rise in activity in the tar sands, the cost of transportation by rail may delay or even stop further development.

And what about another pipeline, in case the construction of the Keystone XL is not approved? Before Canada, the possibility of transporting the oil to the west, to the coast of the Pacific Ocean and from there, in huge tankers, to China is open. Another option is to transport the oil eastward, through existing pipelines, to the US Midwest or the Atlantic coast. But both of these options are problematic. Transporting the oil to the Pacific coast, the less feasible option of the two, would require the construction of a line that would cross the Rocky Mountains and pass through lands owned by Canada's Indian tribes known as First Nations and other indigenous groups in British Columbia, who oppose the passage of pipelines on their lands for fear of leaks and environmental damage others. A pipeline to the Atlantic coast can be installed through an impromptu connection to the network of pipelines that already link Alberta to the east coast of the North USA. In this case, engineers would have to reverse the direction of the oil flow, as Exxon-Mobil did with the Pegasus pipeline, which currently carries crude oil from Illinois to Texas. But older pipelines in which the oil is flowed in the opposite direction to the original flow direction are more prone to leaks. In Pegasus, for example, an oil spill developed from the tar sands in Arkansas in April 2012. Furthermore, the improvement of existing pipelines will most likely provoke strong protest from environmental activists and other parties.

Because of these hurdles, the Environmental Protection Agency and International Energy Agency reports note, the tar sands industry needs Keystone XL to continue to thrive. Alberta's tar sands currently produce 1.8 million barrels of oil per day. Keystone XL will be able to transport an additional 830,000 barrels per day.

Aware of the opposition of environmental organizations, the authorities in the province of Alberta and the energy companies are trying to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the sites of activity in the tar sands. The Royal Dutch Shell company is examining an expensive alternative to the process of extracting oil from bitumen, based on adding hydrogen, instead of heating the bitumen, in order to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. At the same time, the international oil giant began developing plans to install equipment to capture and store carbon dioxide. The project, launched at one of its smaller refineries, is called Quest. The goal, upon completion of the project in 2015, is to store one million tons of CO every year at great depth below the surface of the ground2: About a third of the facility's pollutant emissions. In another similar project, an attempt was made to capture CO2 and use it for increased extraction of oil wells.

Also, Alberta is one of the only oil producing regions in the world where a tax is imposed on carbon emitted into the atmosphere. Today the tax is $15 per ton of carbon and the amount may increase following the ongoing discussions on the subject. The province of Alberta invested the amount of money collected - more than 300 million dollars - in technological development, mainly in technologies designed to reduce CO emissions2 The tar sands. The tax on those emissions "at least gives us a little weapon against the people who attack us about the carbon footprint we leave behind," Ron Leifert, then Alberta's energy minister, told me in 2011.

Efforts to reduce the carbon footprint in the tar sands further increase oil production costs, but so far, these efforts have not been very successful. According to data published by the Canadian Association of Petroleum Companies, the 1.8 million barrels of oil extracted from the tar sands in 2011 caused the emission of more than 47 million tons of greenhouse gases that year.

In 2012, the International Energy Agency conducted an analysis of ways to avoid reaching the two-degree threshold, which concluded that oil production from the Alberta tar sands must not exceed 3.3 million barrels per day until 2035. However, the mining sites whose construction has been approved and those under construction in Alberta may increase The scope of oil production to 5 million barrels per day already by 2030. It is difficult to imagine how it will be possible to continue the mining activity in the tar sands without exceeding the carbon budget framework.

Breaking the carbon budget framework

Is it fair to turn the spotlight on the tar sands? After all, other forms of fossil fuels contribute even more to the global carbon budget, but don't provoke as much outrage. And maybe, unfairly. In 2011, the coal-fired power plants in the US emitted about two billion tons of greenhouse gases - about eight times the amount produced by the mining, refining and burning operations in the tar sands. Many coal mines around the world scar the landscape in exactly the same way and have left behind even greater climate changes. Even so, mines like those in the Powder River Basin of Montana and Wyoming don't spark widespread public protest like the Keystone XL project, and protesters don't tie themselves to railroad tracks to stop the long trains carrying coal from the river basin every day. The US Geological Survey estimates that the Powder River Basin alone contains 150 billion tons of coal that can be mined with the technologies available to us today. Burning all this amount of coal would catapult the world far beyond the trillion ton threshold of the carbon budget.

Australia's plan to increase coal exports to Asia could result in the emission of an additional 1.2 billion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere every year, when burning coal. Compared to these emissions, the share of the tar sands in greenhouse gas emissions is dwarfed, even if we take into account the most optimistic forecasts for the expansion of activity in the area. The US and other countries, such as Indonesia, are planning expansions of their activities in the coal sector. The closure of the US coal industry or even a cut in its activity will offset any expected increase in pollutant emissions from the tar sands due to the construction of Keystone XL, although the two types of fuel in question are used for different purposes: coal, for electricity generation, and oil, for transportation.

Also, as a friendly democracy sensitive to pressure exerted by environmental organizations, Canada serves as a convenient target. On the other hand, companies in Mexico, Nigeria or Venezuela that produce "heavy oil", whose contribution to environmental pollution is no less than that of the bitumen extracted from the tar sands, are not exposed to such severe monitoring and control, despite the high emission rates of CO2 whose activity causes In fact, extracting heavy oil of the same type from an old oil field in California is the most polluting process, emitting more CO2 From any other method of producing oil in the world, including the extraction of bitumen from tar sands deposits in the process of melting. "If you think there is an advantage to producing oil from other sources (other than the tar sands), you are deluding yourself," says chemical engineer Murray Gray, who serves as the scientific director of the Oil Sands Innovation Center at the University of Alberta. "The increasing use of coal in the world worries me much more. "

But oil production from other sources is not developing at such a rapid pace as that which characterizes the oil production industry from Alberta's tar sands, which has grown in the last decade by more than a million barrels per day. If we want to stay within the framework of the global carbon budget, we must use less than half of the oil, gas and coal reserves that we know exist and whose extraction is economically viable. This means that we must leave a significant portion of the mineral fuel - especially the most polluting forms of oil, such as that extracted from the tar sands - lying deep in the earth.

Economic forces may come to the aid of the global environment. Following the extraction of oil from the Bakken oil shale field in North Dakota using hydraulic fracturing (fracking) technology, there was a drop in demand in the US for Canada's "dirty" oil. In response, new infrastructure development projects in Alberta's tar sands, such as the Voyager project to build a refinery at a cost of $12 billion, were canceled. Also recently introduced standards in the USA that require increasing the fuel efficiency of cars will reduce demand, at least in the short term. One way or another, the tar sands are not going anywhere, and they will become an attractive target for oil production again when other oil fields, more convenient for exploitation, are exhausted.

If the Keystone XL oil pipeline is eventually approved, or if an alternative system is established to transport the oil from the tar sands to China, oil exports will most likely increase, and with it the accelerated and invisible accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere. Instead of taking the essential step to not exceed the global warming threshold of two degrees Celsius and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2.5% every year, it seems that we are going to continue emitting polluting gases into the atmosphere and further aggravate the global greenhouse effect. Every atom of carbon emitted from burning fossil fuels, whether it originates from bitumen sands or from other reservoirs, determines our future on Earth.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

in brief

Extracting oil from tar sands and burning it as fuel produces huge amounts of carbon dioxide.

To avoid an average global warming of more than two degrees Celsius, which could cause catastrophic climate change, we must ensure that the cumulative emissions of carbon into the atmosphere do not exceed the threshold of one trillion tons.

The Earth's atmosphere has already passed half way towards the threshold of one trillion tons of carbon; Expanding oil production from the tar sands will accelerate emissions.

If the Keystone XL oil pipeline line is established from Canada to the USA, the production of oil from the tar sands will be accelerated, and this will bring the planet giant steps closer to the threshold of emissions that cannot be exceeded.

Black gold mine

How do you extract oil from tar sands?

Alberta's oil sands have been baked by the heat of the earth's bowels, resulting in a thick, tar-like oil known as bitumen. The bitumen drops surround jagged grains of sand and water, which must be separated from the bitumen so that it can be processed. Generally, ore contains 73% sand, 12% bitumen, 10% clay and 5% water. A byproduct of the process of separating the sticky components is lakes of water filled with toxic sediments.

About the author

David Biello is an associate editor at Scientific American.

And more on the subject

Warming Caused by Cumulative Carbon Emissions towards the Trillionth Tonne. Myles R. Allen et al. in Nature, Vol. 458, pages 1163-1166; April 30, 2009.

The Alberta Oil Sands and Climate. Neil C. Swart and Andrew J. Weaver in Nature Climate Change, Vol. 2, pages 134-136; February 19, 2012.

The Facts on Oil Sands. Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, 2013. www.capp.ca/getdoc.aspx?DocId=220513DT=NTV

The article is published with the permission of Scientific American Israel

5 תגובות

"also"

The Greens are against nuclear power.

The only viable way to reduce carbon emissions

Is to use nuclear power plants instead of stations

which are powered by fossil fuel - mainly coal

which also releases soot that absorbs the sun's heat.

The whole thing is an economic-political decision, to burn

Coal is cheaper - and scares the neighbors less.

It is easy to write what is not good, but what is the solution? Another uneconomic green energy was already the standard in every country without oil the world will return to the stone age after a third world war will break out and billions will die from the bombs, plagues and hunger. Even the black plague will look like child's play and who knows, maybe the world will never return to its developed state. With a few millions of people who will live like in the Middle Ages at best if there is a place left without lethal radiation.

A losing battle upstream, as long as energy prices remain low and there is some technological breakthrough that is currently not in sight, greenhouse gas emissions can only go up. This is human nature and this is the nature of the economy. No economy in the world will sacrifice itself for benefit, however great it may be in the future compared to profit here and now.