Neuroscientist Prof. Alan Snyder owns a strange machine that can activate the genius in each of us. Just before he presses the button, get a short explanation about autism and the limits of human thought

Lawrence Obsorn, New York Times, Haaretz, News and Walla!

I sat on a chair in a concrete basement at the University of Sydney waiting for an electromagnetic pulse to change my brain. My forehead was connected via a set of electrodes to a machine that looked a bit like an old fashioned hair dryer, a machine that was gleefully described to my ears as a "magnetic extracranial stimulator made in Denmark". But it was not just any magnetic extracranial stimulator made in Denmark, but the "Medtronic Mag Pro", and it was operated by Prof. Alan Snyder, one of the best researchers of human cognition in the world.

Medtronic was originally developed as a tool for brain surgery: by stimulating or suppressing certain areas of the brain, doctors could monitor the effects of surgery in real time. But they also noticed that the device had strange and unexpected effects on the brain function of the patients: one moment they lost the ability to speak, and the next they could speak easily but with strange linguistic errors and so on. Several researchers began to test the possibilities inherent in the device, but Snyder was intrigued by one possibility in particular: the fact that people who experienced extracranial magnetic stimulation (TranscranialMagnetic Stimulation, TMS), suddenly demonstrated a degree of genius similar to that found in autistic people.

Snyder has a mischievous image, which stands in stark contrast to that of a distinguished professor, let alone a world-renowned scientist. It has something of Woody Allen. I couldn't stop the doubt that arose in my heart: did I really want this person to reinstall my hard drive? "We don't physically change your brain", he reassured me. "You will feel changes in your thought processes only while you are connected to the machine." His assistant checks the electrodes one last time, then everyone walks away and Snyder turns on the switch.

A series of electromagnetic pulses aimed at my frontal lobes, but I felt nothing. Snyder ordered me to draw something. "What do you want to draw?" He said moaning, "Cat? Do you like to draw cats? So let there be a cat."

I have seen millions of cats in my lifetime, and when I close my eyes I can easily picture them. But what does a cat really look like and how to transfer the image to paper? I tried to draw and got some kind of unknown dotted animal, maybe an insect. While I was drawing, Snyder continued his lecture. "You can call it a machine for increasing creativity. This is a way to change our state of consciousness without using drugs like mescaline. You can make people see the raw data of the world as it is, as it manifests in the subconscious of all of us."

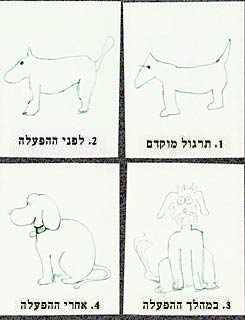

Two minutes after I drew the first picture I was asked to draw again. Two minutes later I tried the third, then the fourth. Then the experiment was over and the electrodes were removed. I looked at my creations. The first cats were square, stiff and unconvincing, but after I was exposed to the extracranial magnetic stimulation for about ten minutes, their tails became livelier, more nervous; Their faces became more handsome and more convincing. They even got cheeky facial expressions.

I would have a hard time saying that these are my paintings, even though I saw how I painted them and all the wonderful details in them. Somehow in a matter of minutes, and with no additional training, I went from a failed colorist to an impressive artist, an expert in the field of feline form. Snyder looked over my shoulder. "Well, what do you think? Da Vinci would be jealous of you." Or turn over in his grave, I thought.

Who is the rain man?

As amazing as the cat drawing lesson was, it was only a hint of Snyder's work and the implications of his cognition research. He used the extracranial stimulator dozens of times on university students and measured the machine's effect on their ability to draw, spell, and perform complicated mathematical operations, such as recognizing prime numbers just by looking. 40% of the subjects connected to the machine demonstrated extraordinary new mental abilities. Snyder's ability to pull off these incredible performances in a controlled environment is more than party fun; This is a breakthrough that may revolutionize the way we understand the limits of our intelligence, and brain function in general.

Snyder's work stemmed from his curiosity about autism. Although there is only partial agreement about the causes of this puzzling (and increasingly common) disorder, it is safe to say that certain traits characterize all autistics: they tend to be rigid, mechanical, and emotionally detached. They demonstrate what autism "reveals", Leo Kenner, called "an anxious and obsessive desire to preserve identity". They tend to interpret information too literally, and use "a kind of language that is not intended to play a role in interpersonal communication".

For example, Snyder says, when autistic subjects come to his university office, they often lose their way in the central block of buildings. They may have visited the place ten times already, but each time the shadows were positioned slightly differently, and the differences were too great for their sense of direction. "They cannot understand the general idea associated with the words 'block of buildings,'" he explains. "If the appearance of the area changes even a little, they have to start from the beginning."

Despite these limitations, there are autistics who belong to a small subgroup of genius autistics ("Asperger's syndrome") who are capable of extremely special performances in the field of thought. The most famous autistic genius is probably the character played by Dustin Hoffman in the movie "Rain Man", who could count hundreds of matches at a glance. But the truth is even stranger: one famous autistic genius in late 19th century Vienna was able to calculate what day of the week every date since the birth of Christ falls on. Other geniuses can speak a dozen languages without having learned them formally, or reproduce on the piano music they have only heard once before. An autistic genius studied by the English doctor J. Langdon Downe in 1887 memorized every page of Gibbon's book "The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire". At the beginning of the 19th century, Gottfried Mind became famous throughout Europe thanks to the amazing pictures of cats he painted.

It used to be thought that the supraverbal thought patterns of autistics constituted a completely separate brain activity from the social, contextual and varied way in which most adults think. Accordingly, the extraordinary abilities of autistic geniuses were considered accidental - almost inhuman feats that normal minds cannot achieve. Snyder claims that all of those assumptions—from the way autistic geniuses behave to the basic brain functions that cause them to behave that way—are wrong. Autistic thought processes are not opposed to normal ones, he says, but are a variation of them, an extreme example.

He came up with the idea after reading the book "The Man Who Thought His Wife Was a Hat", in which Oliver Sachs examines the fine line between autism and a certain type of brain injury. If a neurological defect is the cause of the autistic disability, Snyder wondered, could it also be the cause of their genius-like abilities? By turning off certain brain activities - the ability to think conceptually, unambiguously or contextually - does this allow other brain activities to thrive? In short, can brain damage make you a genius?

In an article from 1999, entitled "Are arithmetic operations with whole numbers a necessary step in thought processes? The secret account of the brain", Snyder and Dr. John Mitchell examined the case of an autistic toddler whose brain, they wrote, "does not operate based on concepts... In our opinion, such a brain can connect to low levels of details that are not available to ordinary people". It seems that "these children are aware of information that is in a kind of raw state or an intermediate state, before it crystallizes into a 'final image'". The most amazing thing, they continued, "is that the brain mechanism that makes it possible to perform calculations at lightning speed may be found inside each of us." And so Snyder turned to extracranial magnetic stimulation in an attempt, as he says, "to improve the brain by turning off parts of it."

Everything is buried in the head

In a way, the autistic geniuses are the biggest mystery in neurology today," says Prof. Joy Hirsch, Director of the Center for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging at Columbia University in New York. "They exist in all cultures and constitute a group of their own. why? how? We don't know. But understanding autistic geniuses will provide us with insight into the entire neurological-physiological basis of human behavior. This is why Snyder's ideas are so exciting - he asks a very basic question, to which no one has yet found an answer."

If Snyder's suspicions are matched, and it turns out that the autistic geniuses do not have a greater power of thought than the rest of us, but a smaller one, then it is possible that each of us began life as a genius. Take, for example, the way young children acquire mastery of complex languages, a mysterious skill that disappears around the age of 12. "We act counterintuitively," Snyder explains. "We say that all those genius skills are actually easy, natural. Our brain performs them naturally. like walking Do you know how hard it is to walk? It's much more complicated

From drawing!"

In order to prove this claim, he connects me again to "Medtronic Mag Pro" and asks me to read the following lines:

One bird in the hand is better

Than two

on the tree

"One bird in the hand is better than two on the tree", I say.

"One more time," says Snyder, smiling.

I repeat: "One bird in the hand is better than two on the tree". He makes me repeat the sentence five or six times, slowing me down more and more until I repeat each word with excruciating slowness. Then he turns on the machine. He tries to suppress those parts of my brain that are responsible for making connections, for contextual thinking. Without them I would be able to see things as the autistic might see them.

After five minutes of electric pulses I read the card again. Only then do I notice - immediately - that the word "on" appears twice on the card. Without the machine I looked for patterns, I tried to connect the words on the page into one familiar and logical whole. But "with the machine", he says, "you started to see what really is

is there, not what you think is there."

Snyder's theories are based on those documented cases where genius abilities appeared almost immediately after a sudden brain injury. He mentions the case of Orlando Searle, a 10-year-old street boy who received a blow on the head and almost immediately began to perform extremely complicated date calculations. Snyder claims that we all have

Searle's powers. "We remember almost everything, but we remember a very small part. Isn't that strange? Everything is here" - he taps his temple with his finger. "Deep inside our minds are buried phenomenal abilities that we lost for some reason when we became 'normal' and perceptive creatures. But what if we can conquer them back?".

Plausible

Not all of Snyder's colleagues agree with his theories. Michael Howe, a renowned psychologist from the University of Exeter in England who died last year, argued that autistic genius (and genius in general) is largely the result of constant practice and specialization. "The main difference between experts and geniuses," he once told the "New Scientist" magazine, "is that geniuses do things that most of us don't bother to learn and get better at."

"If you drew 20 cats one after the other, the drawings will probably get better anyway," says Robert Hendren, CEO of the Mind Institute (MIND) at the University of California. Like most neuroscientists, he doubts the ability of an electromagnetic pulse to stimulate the brain into activity: "I'm not sure how extracranial magnetic stimulation can change the way your brain works. There is a chance that Snyder is right, but the matter is still very experimental."

Thomas Faus, a professor of neuroscience at McGill University who has extensively researched extracranial magnetic stimulation, is even more skeptical. "I don't believe it can cause complex human behavior," he says.

However, even skeptics like Hendren and Fauss admit that by stimulating the activity in one part of the brain, while suppressing the activity of another part, extracranial magnetic stimulation can have impressive results. One of the most successful applications is in the field of psychiatry, where the device is used to silence those "inner voices"

that schizophrenic patients hear, or for the treatment of clinical depression without the negative side effects of electric shock therapy (a company from Atlanta called "Neurontics" is developing an extracranial magnetic stimulation machine for this purpose only. The machine will probably go on the market in 2006, subject to approval by the US Food and Drug Administration).

Meanwhile, researchers at the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke discovered that directing the extracranial magnetic stimulation to the prefrontal cortex allows subjects to solve geometric problems more quickly. Alvaro Pascal Leon, professor of neurology at "Beit Israel" hospital in Boston, who was one of the developers of the stimulator thanks to his work in a laboratory for magnetic stimulation of the brain, even believes that extracranial magnetic stimulation can be used to "prepare" the minds of students before class.

Of course, the whole matter did not go unnoticed by shrewd entrepreneurs and scientists. Last year, the Laboratory for Magnetic Brain Stimulation at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine received a government grant in the amount of two million dollars, in order to develop a miniaturized extracranial magnetic stimulation device that could be used by soldiers who have to stay awake for periods of time. long time "It's not at all something along the lines of 'Star Trek,'" says Ziad Nachas, the medical director of the laboratory. "A large part of our research regarding the correction of cognitive deficits and their effect was done on people suffering from insomnia or sleep disorders. It works".

The day may therefore not be far off when it will be possible to increase the cognitive function of soldiers under normal conditions. And from there, how far is the road to the stage where Americans will walk around with anti-depressant helmets humming on their heads, or with "hair dryers" that improve mathematical ability? Will commercial extracranial magnetic stimulation machines be used to turn boring bank managers into amateur Rembrandts? Snyder even considered developing computer games that require the use of those parts of the brain that are not accessible without the extracranial magnetic stimulation.

"Everything is possible," says Prof. Vilanur Ramachandran, director of the Center for Brain and Cognition Research at the University of California, San Diego and author of the book "Phantom of the Brain". Although Snyder's theories have not been proven yet, he says, they open the door to amazing possibilities: "Today we are at the stage of brain research where biology was in the 19th century. We know next to nothing about the brain. Snyder's theories may sound like 'cases in the dark', but what he says is certainly plausible. Up to a certain point the mind is open, malleable and constantly changing. We may be able to make him act in new ways." About those people who dismiss Snyder's theories casually, he shrugs and says: "Sometimes people close their eyes to new ideas. especially scientists.

Must be important

Bruce L. Miller, a renowned professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, is interested in Snyder's experiments and the way Hella is trying to understand the physiological basis of consciousness. But he mentions that certain fundamental questions about artificially modified intelligence are still unanswered. "Do we really want these capabilities?" he asks. "Wouldn't the way I see myself change if I could suddenly draw amazing pictures?"

It will probably change the way people see themselves, not to mention the way they treat artistic talent. And while this prospect may deter Miller, there is no doubt that others will find it fascinating. But can anyone guess in advance how his life will change as a result of increased creativity, ready-made intelligence or

Instant happiness? Or from the disappearance, instantaneous as well, of those characteristics as soon as the device is turned off?

On our way out of the university towards the roundabout leading back to the center of Sydney, Snyder exudes an abundant and most convincing optimism. "Remember the old saying that we only use a small part of our brains? Maybe that's true. Only now we can prove it physically and experimentally. This is very important. I mean it has to be important, right?"

We stop for a moment on the side of the busy road and look at the haze in the sky. Snyder's eyes narrow curiously as he connects the unfamiliar facts (brown smoke just outside Sydney) and slips into a familiar plot pattern (the bushfires that have been raging in the area for a week). It was an effortless inference, non-verbal thinking of the kind that humans, without the aid of extracranial magnetic stimulation, perform thousands of times a day. Then, in a second, he returns to the conversation and continues his line of thought. "More importantly, we can change our intelligence in unexpected ways. What reason do we have not to want to check it?".

One response

Asperger's doesn't have to be a high IQ. I will collect