The Hebrew University is inaugurating Einstein's private library today

On the occasion of Einstein's 133rd birthday, the Hebrew University will launch a new Albert Einstein website at a press conference on Monday, March 19.

The site will include a complete visual presentation of approximately 2,500 selected documents relating to his scientific work, his public activities and his private life, as well as a complete and advanced catalog of more than 80,000 records of all the documents found in the Einstein archive.

In addition, Einstein's private (and non-scientific) library will be presented to the general public for the first time.

One day in 1919, Einstein's best friend Michael Basso lost all the copies of the publications that Einstein had given him. He turned to Einstein and suggested: Let's publish an edition of your collection of writings, with an introduction that will explain to the reader the essence of the writings. But in the end nothing came of this project.

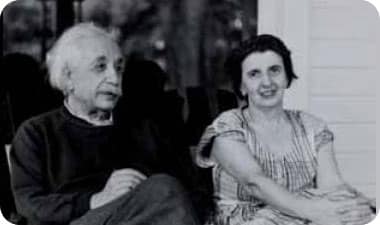

After Einstein's death at Princeton in 1955, Einstein's good friend the economist Otto Natan and his faithful secretary Helen Dux were appointed to be in charge of his writings and all his intellectual property. They were responsible for collecting and organizing the documents and making them accessible to the public. But because they were both so close to Einstein, feelings were mixed with the desire to preserve his legacy.

Helen Dux, who adored Einstein, devoted her whole life to him and served him faithfully for decades, identified with his writings and felt a strong emotion towards them. And Otto Natan was the businessman in the Einstein "mansion". They both therefore decided which documents from the Einstein archive they had were allowed to look at, when and who could look at them. Before the collection was moved to Jerusalem, some writings and letters mysteriously disappeared from it.

Helen Dukes used to hand out Einstein's articles, manuscripts and books with handwritten notes to people she liked, while she didn't let people she liked less near Einstein's writings. The first editor of Einstein's writings Prof. John Stachel - then at Princeton at the time - managed to make copies and save most of the letters before they were sold at auctions.

In 1948, upon the death of Mileva Maric - Einstein's first wife - she passed the love letters to her son Hans Albert Einstein, who was a professor of civil engineering at the University of California, Berkeley. One day Hans Albert Einstein wanted to publish a book about the love letters of his father Einstein and his mother Mileva Marich and edit them. He did not want to publish too intimate letters and he strove to publish the letters that honor his parents. Since Otto Nathan and Helen Dux owned Einstein's intellectual property, they vetoed and threatened to sue if Hans Albert published the book.

As a result, the son Hans Albert kept the letters with him and prevented the Einstein "estate" from receiving them. The letters were only discovered after he died. In 1985, the editor at the time of the Einstein Project, Robert Shulman, heard about early "love letters" in the hands of Einstein's relatives in California and discovered the love letters between Einstein and his first wife Mileva Marich. In 1986 Shulman located Evelyn Einstein, Einstein's adopted granddaughter, in Berkeley. However, she did not have the letters. The search led to a bank vault in Los Angeles, where 400 hoarded family letters were deposited by Evelyn's stepmother, Elizabeth Ruboz Einstein.

The publication of the first volume of the collection of Einstein's writings was delayed so that the first 51 love letters could be included. The book was published in 1987 and in 1992 Shulman Vern's book Albert Einstein: The Love Letters was published. The book included an English translation of the love letters between Albert Einstein and Mileva Marich. There are 54 letters from the period 1897 to 1903. Of these, only 11 letters are from Mileva. Since they probably answered each other by returning letters, it is most likely that Einstein did not keep many of the letters Milva sent him.

At the beginning of 1982, all the property from Einstein's "estate" was transferred to the Hebrew University in accordance with Einstein's will and this is how Einstein's "estate" was dissolved. Helen Dukes died shortly thereafter in February 1982 after completing her role as "Keeper of the Einstein Flame".

for further reading:

Martínez, Alberto, “The Myriad Pieces of Einstein's Remains”, Annals of Science 68, 2011, pp. 267-280.

Below is presented here for the first time a selected list of books from Einstein's private library from Princeton which is in the Einstein archive. An interesting fact is that most of the books are in English and most of them deal with popular science. And Einstein spoke German until his last day and spoke English with a funny accent (he used to say "I Tink"). And so you can go to the library and look for them and read the books that Einstein loved:

de Bothezat, George, Back to Newton, a Challenge to Einstein's Theory of Relativity, 1936, New York: Verlag GJ Stechert & Co.

Curie, Eve, Madame Curie, 1938, Paris : Gallimard.

Dingle, Herbert, Science and human experience, 1932, New York: Macmillan.

Dingle, Herbert, Through science to philosophy, 1937, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Einstein, Albert und Leopold, Infeld, Physik als Abenteuer der Erkenntnis, 1938, Leiden: AW Sijthoff.

Einstein, Albert, and Infeld, Leopold, The Evolution of Physics, edited by Dr. CP Snow, 1938, The Cambridge library of Modern Science, Cambridge University Press, London.

Einstein, Albert und Infeld Leopold, Die Evolution der Physik : von Newton bis zur Quantentheorie, 1938/1956, Hamburg : Rowohlt.

Albert Einstein. Leiden: AW Sijthoff.

Einstein, Albert, The Meaning of Relativity, Princeton: Princeton University Press, editions: 1922, 1945, 1950, 1953.

Freundlich, Erwin Finlay, The foundations of Einstein's theory of gravitation, authorized English translation by Henry L. Brose; preface by Albert Einstein; introduction by HH Turner, 1922, New York : GE Stechert.

Gamow, George, Mr. Tompkins in Wonderland: or stories of c, g, and h, illustrated by John Hookham, 1940, New York : Macmillan.

Gamow, George, One, two, three... infinity : facts & speculations of science, illustrated by the author, 1947, New York: Viking Press.

Haldane, Richard Burdon, 1st Viscount, The philosophy of humanism, and of other subjects, 1922, London: J. Murray.

Henderson, Archibald, Lasley, JW Jr., and Hobbs, AW The Theory of Relativity Studies and Contributions [textbook], 1924, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC

Hogben, Lancelot Thomas, Mathematics for the million: a popular self educator, illustrations by JF Horrabin, 1937, London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1940-1951.

Infeld, Leopold, The world of modern science: matter and quanta; translated by Louis Infeld; with an introduction by Albert Einstein, 1934, London: V. Gollancz.

Joliot-Curie, Frederic, Cinq annees de lutte pour la paix, Articles, Discourses, et Documents (1949-1954), 1954, Paris: Éditions "Defense de la paix".

Kayser, Rudolf, Kant, 1934/1935, Wien: Phaidon-Verlag.

Langevin, Paul, Oeuvres scientifiques de Paul Langevin, 1950, Paris: CNRS.

Levi-Civita, Tullio, Der absolute Differentialkalkül und seine Anwendungen in Geometrie und Physik, 1928, Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Levi-Civita, Tullio and Enrico Persico, Lezioni di calcolo differenciale assoluto: raccolte e compile, 1925, Roma: Alberto Stock.

Levinson, Horace C., Zeisler Ernest Bloomfield, The law of gravitation in relativity, 1931, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Lorentz, Hendryk, Antoon, Elektr. und opt. Erscheinungen in bewegten Körpern, 1906, Leipzig: BG Teubner.

Lorentz, Hendryk, Antoon., Einstein, Albert, and Minkowski, Herman, Das Relativitatsprinzip, 1922, Leipzig und Berlin: Druck und Verlag von BG Teubner.

Lynch, Arthur, The Case Against Einstein, 1932, London: Philip Allan.

Møller, Christian, The Theory of Relativity (Based on lectures delivered at the University of Copenhagen), 1952, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Plesch János, Die Herzklappenfehler including der allgemeinen Diagnostik, Symptomatologie und Therapie der Herzkrankheiten, in Spezielle Pathologie und Therapie innerer Krankheiten, hrsg. von F. Kraus ua, 1919-1927, Berlin etc: Urban und Schwarzenberg.

Plesch, Johann, Physiology and pathology of the heart and blood-vessels, 1937, London, Humphrey Milford, Oxford university press.

Rahakrishnan, S, and Gandhi, Mahatma, Mahatma Gandhi, essays and reflections on his life and work: presented to him on his seventieth birthday, October 2nd, 1939, 1949, London: George Allen & Unwin.

Reichenbach, Hans, From Copernicus to Einstein, translated by Ralph B. Winn, 1942, New York: Philosophical Library.

Reiser, Anton [Rudolf Kayser] Albert Einstein: A Biographical Portrait, 1930/1952, New York : Dover.

Robb, Alfred, A Theory of Time and Space, 1914, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Russell, Bertrand, Our knowledge of the external world, 1926, London: Allen & Unwin.

Samuel, Herbert Louis Samuel, Viscount, Essay in physics, with a letter from Albert Einstein, 1951, Oxford: B. Blackwell.

Schilpp, Paul Arthur (ed.), Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist, 1949, La Salle, IL: Open Court.

Silberstein, Ludwik, The theory of relativity, 1914, London: Macmillan.

Stalzer, Theodore, Beyond Einstein: a re-interpretation of Newtonian dynamics, 1936, Philadelphia: Dorrance and company.

Stone, Isidor F., Underground to Palestine, 1946, New York: Boni & Gaer.

Violle, Jules, Lehrbuch der physik, Mechanik I, Mechanik II, deutsche Ausgabe von E. Gumlich et al., 1892-1893, Berlin: J. Springer.

Wells, HG, The fate of Man; an unemotional statement of the things that are happening to him now, and of the immediate possibilities confronting him, 1939, London: Secker and Warburg.

Whitehead, Alfred North, The principle of relativity with applications to physical science, 1922, Cambridge: University Press.

Winkelmann, Dr. A. unter Mitwirkung von R. Abegg et al., Handbuch der Physik, herausgegeben von Band 4 Elektrizität und Magnetismus.