George Price discovered the formula for altruism in nature, decided to live an altruistic life himself and thereby determined his destiny... The book is published by "Attic Books and Yediot Books" translated by Michal Ben-Yaakov.

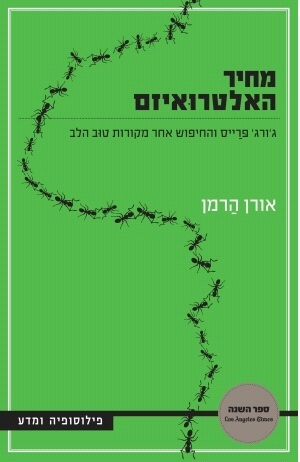

The Price of Altruism George Price's story. by Oren Herman. From English Michal Ben-Yaakov. 485 pages:

The Price of Altruism George Price's story

by Oren Herman

From English: Michal Ben Yaakov

Attic Books and Yedioth Books

In the winter of 1975, in cold London, in an abandoned house, George Price - homeless, sick, genius - killed himself. And these are the people who came to the funeral: five homeless people and two of the most important biologists in the world, Bill Hamilton and John Maynard Smith. The five homeless people were witnesses to the way in which Price tried to realize in his life, until the end, the principle of generosity; The two professors knew from the height of their scientific fame that the man who ended his life at the age of 52 left behind a simple, elegant, and far-reaching mathematical formula: altruism in nature is indeed possible!

The price of altruism is the story of the lifter who, in his tortuous way, managed to crack the scientific riddle that has not ceased to trouble naturalists, especially since Darwin's theory of evolution is the basis of modern biology: if nature is conducted as a cruel competition in which the "fittest" manage to survive, how do we explain the many evidences that testify On manifestations of generosity, consideration for others, to the point of self-sacrifice? And maybe this is the case with animals, but not with humans?

Oren Harman, who holds a doctorate from the University of Oxford, is a professor of the history of science and heads the curriculum for science, technology and society at Bar Ilan University. He is a documentary filmmaker, essayist and author of The Man Who Invented the Chromosome (Harvard 2004), Rebels in Biology (Yale 2008), and Biology Outside the Box (Chicago 2013). He lives in Tel Aviv.

Chapter 1: War or Peace?

He will wait until dusk. This would be the best time to slip away unseen. As he packed a small suitcase, memories flashed through his mind of his passionate lecture last night at the Geographical Society, about the glacier formations in Finland and Russia. The lecture was successful, he thought. The country's top geologist, Barbeau de Marny, spoke in his praise. They even offered to appoint him president of the company's physical geography unit. Years of frozen journeys to the ends of the earth finally paid off. But now he must concentrate. He must escape. "You better go out through the service stairs," one of the maids whispered in his ear.

A horse-drawn carriage stood at the gate. He jumped in. The coachman whipped the horses and turned to Nevsky Prospekt, the wide avenue planned by Peter the Great in the city that has since been named after him. A short drive to the train station, and from there to freedom! Russia is a vast country, and in its remote eastern provinces he intended to establish a "land league", like the one that was to gain great power in Ireland in the coming years. It was the early spring of 1874.

Suddenly another carriage joined them at a gallop. To his surprise, one of the two weavers who had been arrested the previous week waved at him from the carriage. Perhaps the man has been released, he thought, and has an important message for me. He ordered the coachman to stop, but before he could bid the weaver farewell, another man appeared beside him; Two years of secret meetings, dressing up and sleeping in strange beds came to an end. The second person, a detective, jumped into his carriage and shouted: "Mr. Borodin, Prince Kropotkin, I am arresting you!" Later that night, in the depths of the infamous "Third Section", a stern police colonel read the indictment in his ears: "You are accused of belonging to a secret society whose purpose is to overthrow the existing system of government and of conspiring against the holy personality of His Imperial Highness." For Prince Pyotr Alekseevich Kropotkin, known as Borodin, the game is finally over.

• • •

At the very same time, across the Baltic Sea and the North Sea, Thomas Henry Huxley tightened his bow tie and prepared to open, together with the president, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, the Thursday meeting of the "Royal Society" at Burlington House, Piccadilly in London. Images from his afternoon carriage ride flashed in his head like fireflies: swindlers, burglars, forgers and whores, delusional clergymen, dirty boxers and promoters - this was the Victorian underworld that made its way into the holy of holies of science in England. He knew well the bibs and the nests of the fever; That's where he came from. Huxley sank into the velvet-upholstered oak chair and cast a strained gaze across the room.

He was born in 1825, above Italy in Ealing, a small town about twenty kilometers west of London. At the age of ten, when his unemployed father could no longer support his family, Thomas had to leave school to earn his living. He was soon apprenticed to his brother-in-law, a "beer-drinking, opium-chewing" doctor in Coventry, who passed him on to a seedy Mesmerist (believer in the flow of "spiritual energy" between inanimate objects and the body) doctor in London. At times the young Huxley felt that he was about to drown in the "ocean current of life" that was then London, as biographers will one day write - a city teeming with "prostitutes, pimps, headhunters, thugs". He took refuge in the depressing pharmacy, grinding medicine in solitude. Gradually, he became proud and angry: how could the members of the middle class remain so indifferent and cold, he wondered in his diary and in the countless letters he sent to friends, in the face of such blatant and debilitating suffering?

Through hard work and determination, Huxley won a scholarship to Charing Cross Hospital, and later the Gold Medal for Anatomy and Physiology at the University of London. At the age of twenty, in order to pay off his debts, he joined the Royal Navy as an assistant surgeon, and went aboard HM Rattlesnake to patrol the coasts and interior of Papua New Guinea and Australia. He dissected and documented strange alien invertebrates from the wild southern waters, and the specimens and articles he sent home soon earned him a reputation as an expert on oceanic hydrangea. When he was twenty-five years old, he was elected to the "Royal Society". Not much time passed, and he was a professor of natural history at the Royal School of Mines, the head of the Fuller Chair at the "Royal Institution" of Great Britain, the head of the Hunter Chair at the Royal College of Surgeons, and the president of the "British Association for the Advancement of Science".

He thumbed through the papers in front of him. The Royal Society, the seat of Britain's greatest scientists for over 300 years, faced dramatic changes - changes that reflected the face of the nation. Gone are the manners of the aristocracy of years past, the unquestionable loyalty to the crown and the church. when they started

Doctors, capitalists, and even those strange birds, "academics", to climb the social ladder, a fresh wind blew in. The new patrons were merchants and builders of distant empires, not "blue-blooded dilettantes" or "spider-stuffing priests". To Britain itself, as well as to the noble royal society, the new gods were “useful and serviceable to the state; The new priests, the technocrats and the experts". I mean, people just like Huxley.

At the beginning of that week Huxley was the guest of the Radical Party in Birmingham. He was invited to speak at the ceremony of removing the lotus from the statue of the chemist Joseph Priestley. While the fathers of the city strain their ears to hear the origin of his lips, he painted for the citizens a vision of "rational freedom" encouraged by a state driven by science. The post office, the telegraph, the railway, vaccinations, sanitation, road construction - all these would be profitable if managed by the state. Improving the lives of British citizens in this way is the only way to stave off the bloody revolutionary volcano that will torment the rest of Europe.

Huxley cleared his throat to open the meeting. He calmed down. The year was 1874, and he was the secretary of the "Royal Society". The Imperial Botanist, Hooker, who sat next to him, had just refused a knighthood, which he considered beneath the dignity of science. Huxley smiled to himself. If a little boy from Ealing can do it, then the system is right and just, after all. In a world of bloodthirsty competition, he clawed his way from the underbelly to the pinnacle of Victorian life. With his fiery spirit - "dissecting monkeys was his strong point, and dismembering people was his weakness", the Pal from Gazette wrote about him - Huxley was a professional, impartial public servant, at the service of the modern, benevolent state.

"My colleagues, I call the yeshiva to order."

• • •

A few days and inquiries later, when the carriage crossed the palace bridge over the Neva River, Kropotkin knew he was being taken to the dreaded Petropavlovsk fortress, although the stout Circassian officer who accompanied him said not a word. Here, according to the rumor, Peter the Great tortured and killed his son Alexei with his own hands; Here Princess Tarkanova was kept in a cell full of water, "with rats climbing on her from all sides to save herself from drowning"; Here Yekaterina buried political prisoners while they were alive. And this is also where prominent writers were recently banned: Reliev and Shevchenko, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Pisarev. The revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin also spent eight difficult years here before the Tsar gave him the opportunity to go into exile in Siberia, an option he chose willingly. Bakunin fled from Siberia to Yokohama in 1861, and from there to San Francisco, to New York, and finally to London. "Can we get oysters here?" roared the great anarchist when he burst into Alexander Herzen's London apartment, calling for revolution and exile. With these thoughts in his head, Kropotkin smiled to himself and promised himself: "I will not die here!"

He was immediately ordered to undress and put on the prison clothes: a green flannel robe, huge woolen socks "amazingly thick" and yellow slippers, so big that it was difficult to walk without them falling off his feet. The treatment given to the prince was like the last of the prisoners. Still, faint vestiges of respect for the aristocracy could be seen in the old commander of the fortress. General Korsakov looked visibly embarrassed. "I'm a soldier, and I'm just doing my duty," said Mbatto. Kropotkin was marched through a dark corridor patrolled by armed sentries. A heavy oak door closed behind him, and a key turned in the lock.

The room was a fortified cell, "intended for a large cannon", Kropotkin later wrote in his memoirs, with an iron bed, a small oak table and a stool. The only window, a long narrow opening in a wall that was five meters thick, closed with an iron grate and a double iron window frame, was so high that he could barely reach it with his outstretched hand. Absolute silence prevailed in the place, and to relieve it he started singing defiantly. "Do I have to say hello to love?" Zimmer from his favorite opera, Ruslan and Ludmilla by Glinka, but was immediately distracted by a bass voice behind the door. The cell was dim and damp. The prince measured his surroundings and concluded by telling himself to maintain physical fitness. He crossed the room from corner to corner in ten steps. If he walks back and forth 150 times, he will cover one mile - about a kilometer. In that place he determined that he would go seven times every day: two in the morning, two before dinner, two after dinner and one before bed. And so he did, day after day, month after month. And as he walked, a sparrow called to his thoughts.

• • •

Darwin called him "the good and benevolent messenger for spreading the gospel", although "good" and "benevolent" may not have been the appropriate words for the whipping tongue of "Darwin's Bulldog". For Huxley, the alternative was to "lie still and let the devil win", since the opposition to the logic of materialism and evolution seemed to him no less than the handiwork of the devil. Richard Owen, Britain's leading anatomist and Darwin's bitter enemy, called Kesley a deviant with "some brain defect, perhaps congenital", for not denying the existence of a divine will in nature, but such things only fueled the inner fire that ignited him. Finally, from the heights of the "Royal Society", Huxley - "the devil's disciple" in the eyes of his enemies - could begin to bring about the revolution.

The first blow came from Russia. Vladimir Kovalevsky came to London to work on the evolution of the hippopotamus, and soon became friends with Huxley. Darwin's philosophy, about the origin of species and the changes wrought in them by the merciless hand of nature's blind arbiter, has repeatedly been met with satanism and contempt in articles in the popular press and in public debates in museum halls. And yet, evolution still remains on the fringes of real scientific discourse. Over a decade after the publication of the Origin of Species, not even one article related to Darwinism has been printed in the Philosophical Transactions of the "Royal Society". She stubbornly stuck to "facts" and avoided "theory", and distanced herself as far as her blue-blooded nobility allowed her from any controversial matter. But Huxley and his fellow X-Club were now the new masters. When the secretary read Kovalevsky's article to the company, George Gabriel Stokes complained that it was an abomination to allow a nihilist known to the Russian secret police to spout such nonsense. Comparing Darwin's speculations to Newton's axioms is a blow to the very foundations of knowledge. For Stokes, who was a professor with a distinguished chair of mathematics at the University of Cambridge, the "continuous curve" connecting the acts of creation was a piece of "sacred geometry", the exact opposite of "creation by whim". But Huxley organized sympathetic judges, and the article "On the Osteology of the Hippopotami" soon appeared among the pages of the Transactions. It took hippopotamuses and a Russian nihilist for this, but the eager Elm of Ealing finally thawed the stagnation of the "Royal Society". A flood of "free thought" was about to break through the pearly gates of England's scientific holy of holies.

• • •

Kropotkin was born in Moscow in the winter of 1842. His maternal grandfather was a Cossack army officer - some say famous - but his father's side gave him the truly important genealogy. The Kropotkins were a scion of the Rurik dynasty, the first rulers of Russia before the Romanovs. In the days when a family's wealth was measured by the number of its serfs, the family had close to XNUMX souls in three different provinces. There were fifty servants in the house in Moscow, and twenty-five more in the Nikolskoye country estate. Four riders looked after the horses, five cooks cooked the meals, and a dozen men served the dinner.

The world into which Petar was born was one of theresa trees, crafts, samovars, sailor suits and sleigh rides, "a taste of tea and jam, which sharpened and sweetened in the face of the vast and empty prairies beyond the garden and the imminent end of it all."

Not everything was idyllic. Like other famous sons of the Russian landed aristocracy - Herzen, Bakunin, Tolstoy - Peter developed an aversion to that particular flavor of Oriental tyranny baked in the juice of Prussian militarism and coated with a thin layer of French culture. Ivan Turgenev's short story, "Momu", describing the hard life of the serfs, came as a sensational revelation to an indifferent nation: "They love just like us; is it possible?" Sentimental urban women cried out who "could not read a French novel without shedding tears over the plight of the noble heroines and heroes". In young Peter's mind harsh images were engraved: the old and gray man in the service of his master and chose to hang himself under the master's window, the brutal destruction of entire villages due to the disappearance of a square of bread, the young girl whose only escape from a forced marriage was to drown herself in the river. More and more, some members of the ruling classes in Imperial Russia became aware of the ugliness and barrenness of the feudal world into which they were born, and those among them who were thinking and caring people began to worry about the future of their beloved country. Many wondered: what should be done?

Alexei Petrovich Kropotkin, a retired army officer who had never seen actual military activity but had lived his whole life as a military man, thought he knew very well what his son should do: Peter's mother, who had artistic tendencies, died of tuberculosis when he was four, and from then on his father began to educate him to the life of the army. When the boy was eight years old, his father had a golden opportunity to present him at a celebratory ball in honor of Tsar Nicholas I's 25th wedding anniversary. Little Peter, dressed as a Persian page with a bejeweled belt, was hoisted onto the stage by his uncle, Prince Gagarin, for the Tsar's scrutinizing eyes. Nikolai took hold of the child's arm, they led him to Maria Alexandrovna, the pregnant wife of the heir to the throne, and said: "This is the son you should bring me."

The Tsar would not live to swallow his words, but neither would his successor. The Czar's Guard Corps in St. Petersburg was the training camp for Russia's future military elite. Only 150 boys, most of them sons of the court aristocracy, were accepted into the elite unit, and at the end of their training they could choose which regiment to join.

The sixteen outstanding ones were even luckier: they would be the personal assistants of the members of the imperial family - the most coveted entrance ticket to a life of influence and prestige. Peter was sent there at the age of fifteen, much to his chagrin, but despite this he graduated at the top of his class and became the personal assistant of Alexander II, whose father Nikolai had passed away a few years earlier. The year was 1861, and the uprisings became more and more violent, the opposition much louder and more destructive. The new Tsar was under increasing pressure and was going to set the serfs free. When he finally signed the order of liberation, on March 5 (according to the old Russian calendar), Alexander seemed sublime in Peter's eyes. But it was a fleeting emotion. At first, Peter was captivated by the glow of the ornate palace rooms, with courtiers in gold-embroidered uniforms standing along the walls ready to fulfill any wish. But he soon saw that these trifles occupied the court at the expense of matters of real importance. Power, he began to see, nourishes and corrupts.

Peter's role was to accompany the Tsar as a shadow, close enough and far enough to be "present absent". From this distance, the glow of the aura that seemed to be seen before around the body of the imperial ruler slowly faded. The Tsar was untrustworthy, sloppy and vindictive, and many of those around him were even worse. In the Guards Corps, Kropotkin learned to march and retreat, to build bridges and fortifications, but even then he knew that what really interested him was something completely different. Secretly, he began to read the North Star, the critical journal that Herzen published in London, and even edited a revolutionary newspaper. When the time came for him to choose an appointment, he decided to migrate far away to eastern Siberia, to the Omur region that was annexed to Russia. His father and fellow cadets were amazed - after all, as a sergeant in the guard, the entire army was open to him. "Aren't you afraid to travel so far?" Tsar Alexander II asked him in bewilderment before setting off. "No, I want to work. There is certainly a lot to do in Siberia to apply the major reforms that are about to take place." "Go therefore; You can bring benefit anywhere", said the tsar, but the expression on his face spoke of fatigue and complete surrender so much that Kropotkin thought to himself, "He is a complete man".

• • •

Thirty years before Kropotkin set out to the aforesaid, Charles Darwin set sail aboard the HMS Beagle. In October 1832, en route to Buenos Aires, Darwin noticed swarms of phosphorescent zoophytes, each smaller than a tip of iodine. They illuminated the waves with a pale green light around the ship piercing the darkness of the ocean. Darwin knew the accepted explanation: God created the tiny sea creatures to help sailors escape the remains of shipwrecks on dark nights. This is the version of teleology, the backbone of the natural theology tradition on which Darwin's contemporaries grew up.

But the scholar from Shrewsbury was not ready to accept the grace of God as a substitute for a scientific explanation. There was no doubt in his heart that the glow designed to guide wayward ships was nothing more than a simple phosphorescent caution derived from millions of decaying bodies of dead zoophytes trapped among the living ones—a process by which the ocean cleanses itself. This was to his taste a sufficient purpose, with or without the grace of the good God. The true beauty of nature will only be revealed by discovering nature's own laws, not God's. Reverend William Paley saw the creations of nature as proof of divine design - and how else can one explain the presence of a polished crystalline lens in the eye of a trout, or the aerodynamic perfection of an eagle's wing? But the answers in his book The Theology of Nature now seemed to Darwin like questions: if the answers are sought in the laws of nature, and not in the acts of God, how can one explain the miraculous correspondence between the forms of organisms and their functions? How did nature come to look so perfect?

One way to examine the problem would be to investigate the defects of nature in particular, defects that have aroused puzzlement for a long time, and that the attempt to explain them with arguments of planning did not go well. Why do the Kiwi birds, who lack the ability to fly, have the remains of wings, or the snakes the remains of leg bones, or the blind moles a memory of what used to be eyes? The mysteries of biogeography also occupied his mind a lot: why are there fewer native species on the islands than on the mainland? Where did these species come from? Why are they so similar to the mainland species if their natural environments are so different? Darwin, who was a great believer in the immutability of species when he left, returned to England in October 1836 inclined to a more dynamic view of nature and its ways. Although he was still not sure of the ability of the law of nature to explain all the mysteries, he returned from his five years at sea with "such facts [that] would undermine the stability of the species".

Then, in October 1838, something of crucial importance happened: Darwin read the Essay on the Principle of Population by the Reverend Thomas Malthus. Malthus, who used to be a professor of political economy, wanted to show, through the idea that population grows geometrically while the amount of food available grows arithmetically, that famine and wars, suffering and death do not arise from a flaw in this or that political system, but are the inevitable result of a natural law. Darwin, who was a Whig and supported legislation to alleviate the condition of the poor, disapproved of Malthus's reactionary political approach, but applying the priest's law to nature was a different story. Because he saw in his travels the war for existence that prevails everywhere in nature, he immediately understood that "under these circumstances, good variations will tend to be preserved, and not good ones - to be destroyed. The result will be the formation of new species. At last," he wrote, "I have found here a theory to work by." Evolution by natural selection is nothing less and nothing more than "the doctrine of Malthus, as it manifests itself in the entire animal and plant world."

After all, if there was one sweeping conclusion that Darwin learned from the voyage, it was the tremendous richness of life on Earth. On the massive tendrils of the "wonderful" seaweeds on the shores of Tierra del Fuego, which stretch tens of kilometers into the dark depths of the ocean, Darwin found countless plates, molluscs, clams and crustaceans. When we shook them, there emerged from them "small fish, shells, squids, crabs of all kinds and sizes, sea eggs, starfish, beautiful sea cucumbers, sea worms and crawling sea nymphs of many different shapes." The "great twisted roots" reminded Darwin of tropical forests infested with every imaginable ant and beetle, teeming underfoot with giant capybaras and slant-eyed lizards, with dusky falcons hovering overhead. He saw there greatness and endless variety. “The form of the orange tree, the coconut, the palm, the mango, the tree fern, the banana,” Darwin wrote nostalgically of the tropical panorama that unfolded before his eyes in Bahia as the Beagle made her way home, “will remain clear and distinct; But the thousand illusions that trap these into one perfect landscape must be dimmed; And yet they leave, like a story we heard in childhood, a picture full of unclear but incredibly beautiful characters."

But Darwin knew the truth, and it is that nature is one big cacophonous war - violent, unforgiving and cruel. Because if the fertility rates of wild populations are so high, that if there is nothing to limit them they grow exponentially; And if it is known that the size of populations remains stable over time (exclude seasonal fluctuations); And if Malthus was right - and he was obviously right - in saying that the resources available to each species are limited - then it follows that there must be fierce competition, or a war for existence, between the members of the species. And if there are no two identical individuals in the population, and there are variations that increase the fitness of certain individuals, i.e. cause their life chances to be higher than others, and these are inherited - then it follows that selection and preference of the more adapted will lead, over time, to evolution. The consequences were something hard to imagine, but Darwin's logic was impeccable. From the "war of nature, from hunger and death" the most sublime creatures were created. Malthus brought about a complete "conversion" in him, a conversion - so he wrote to his loyal friend Joseph Hooker in 1844 - "which is like confessing to murder."

13 תגובות

The strange thing is that the address of this page is listed as: cost-of-altroism, when the book was originally called in English

The-Price-of-altruism.

Also "price" but also in the name of Price (and let's say a slang for the incorrect spelling of the word altruism in English).

The Jewish people, one-third of which perished in the Holocaust in Europe, survived perhaps with the help of prayers to the Holy One, blessed be He, but for sure almost one hundred percent with the help of altruism, that is, the Jews helped each other even though they risked their lives, and perhaps even some of them were murdered and slaughtered, of course we cannot forget the followers of the nations of the world who helped For Jews like the Swedes - Raoul Wallenberg, and Oskar Schindler, but mainly the Jews as a people and as individuals helped each other, in order to be saved from the clutches of the Nazis, so that the Jewish people survived with the help of prayers but mainly with the help of altruism, which is the exact opposite of Darwin's theory on the origin of species and natural selection...

"The appearance of an altruistic individual in a group reduces its survival to almost zero"

why?

I think this is not true!

But even assuming this is true:

It is possible that a particular individual will be harmed due to being altruistic. But there's a good chance he'll produce altruistic offspring like him. And they also have a good chance of producing altruistic offspring, therefore after a relatively small number of generations the advantage of altruism will be much greater than the disadvantage at the beginning stage.

ב

beginning,

The claim that a biological organism, a single individual or a group of individuals, behaves according to a simple mathematical model is, in my opinion, a nonsensical claim. A biological organ is a very complex organ that acts subject to a large number of influences. An attempt to simplify the operation of a biological organ by ignoring most of the influences on it, in order to create a simple mathematical model, is an attempt destined for failure. The failure is in the oversimplification that makes the model disconnected from reality. Why do mathematical models require oversimplification? Because without it, the calculation becomes astronomical and therefore unfeasible.

Second,

It seems that you are confusing two characteristics related to altruism.

First characteristic: the enormous advantage of a band of animals that operates in a cohesive manner (which requires social sharing, including altruism).

Second characteristic: how can evolutionary development be explained, from a situation where there is a group of animals devoid of altruism to a group of (more developed) animals that have adopted altruism.

Regarding the first characteristic, there is no problem. Most scientists will accept its correctness, with or without a mathematical model.

Regarding the second characteristic, here there are serious disputes and pathetic attempts in my opinion to explain evolution.

The difficulty is that according to the accepted Darwinian method, what is called the evolution of the individual, the appearance of an altruistic individual in the group reduces its survival to almost zero. Therefore the trait of altruism will not take root, it will disappear immediately after it appeared.

============================

Continue in a separate message.

Yaron:

1) You did not refute.

This is not about a single individual with a good heart. This is a whole group that acts altruistically.

The chances of individuals in this group to survive and produce offspring are much higher than the chances of a group of egoists.

2) Because it is natural sciences and not mathematics. The proof is by way of experiment or observation of what happens in nature. Mathematical calculations and "proofs" in logical ways are not suitable for the natural sciences. Since we are not able to perform an experiment on such a large scale, we are forced to check according to observations in nature.

From these observations it appears that altruism is a very important trait in the survival of animals that live in a group.

Smart or stupid is a difficult question. Nature does not ask such questions. In the appropriate nature survives. If the fit is the fool then the fool will survive. Wisdom or stupidity is only a matter of human definitions.

Altruism is an instinct and it is expressed in any situation and not only in "no choice" situations.

Like for example the mother's instinct to take care of her offspring. She will take care of him in any case and not only in "no choice" situations.

Let's intuitively refute the argument you raised not out of disdain but out of common brainstorming. But that chimpanzee with "good heart" genes will die before he could pass his genes on. At least let's say that statistically after 10 generations, the chances of the genes of the "smart maniac" passing on are greater.

So after 10 generations there are no more "good heart" genes, only maniac genes.

The group survived, but without altruists. The greatness of Price, who proved that the genes of the altruists are passed on. Let us help you: that altruist is also smart, and his genes may be passed on. He improves the chances of his genes passing, since he is not just a donkey jumping in the head, but only in a situation where there is no choice: there is no good thing in dying for our country.

It is not clear why complicated formulas are needed.

One can describe a case that immediately and unequivocally proves the importance of altruism.

for example:

A group of chimpanzees encounter a tiger.

Suppose one of the group members is in an inferior position against the tiger. And his fate is bad and bitter.

If everyone takes care of themselves Venus. That individual who is in a disadvantageous position will be preyed upon.

and then:

The group of chimpanzees will be smaller and weaker when more obstacles appear.

However:

Suppose another chimpanzee or a group of chimpanzees attacks the tiger.

Of course, everyone in the group puts themselves at risk.

But the gang's chance of survival is much greater if they bail out for the friend in trouble.

The amount of cases similar to this in nature is so great that it can be said that altruism is not a marginal thing but a very significant factor in a group's ability to survive in nature.

I bought the book. I decided to understand Price's equation from Wikipedia and the reference it referred to, because it seems to me that they reached achievements there that are relevant not only to biology and banking, and can be applied to the reconstruction of weak signals.

Also the fact that Price estimates according to variance (variance), which is the width of the dispersion around the expectation and only then links to the expectation - something I did not know before. Every time I enter something new, I first read a popular book on the subject. I understood that Price proved that altruism is a winning/accepted strategy in evolution and gene inheritance.

I'm interested in the evolutionary game theory section (Maynard Keynes II, not the economist), and Fries's theory. The calculation that in genetic lineages that are 100,000 years old - it is possible to identify a residual genetic connection between a resident of Asia and a resident of Africa, to genetic material from a 100,000 year old skull - how it was done also seems interesting to me.

Such theories seem to me to be useful in science in any field.

Excellent and accurate book, one of the best books I have read. Oren Harman weaved together in one book the history, biology and philosophy of one of the most fascinating and controversial fields in the life sciences. Really recommended.

Those who really want to gain insight into the reasons for altruism will not learn much from Oren Herman's practical stories.

About a year ago, an in-depth study was done on altruism and its necessary part in advanced social structures, so-called eusocial societies. The research was done by one of the greatest biologists in the field of socialization, named Edward Wilson.

Below is a link to a series of streaming lectures where he explains the main points of his thesis.

In a series of streaming lectures in a streaming format

http://fora.tv/2012/04/20/Edward_O_Wilson_The_Social_Conquest_of_Earth

Edward Wilson also published the main points of his thesis in the format of a popular science book to be read

the social conquest of earth

There is no translation of the book into Hebrew, and there probably won't be in the next few years, for many reasons that are not the place to go into detail here.

One thing that needs to be specified is that Wilson's thesis was harshly criticized by the biological scientific establishment, not because Edward is grossly mistaken, but because the biological scientific establishment is very conservative, it is difficult for it to digest innovations that are not purely cosmetic. I don't know if Wilson's thesis is accurate or not, but it at least breaks the ground for new insights.

I hope my response here doesn't come off as garbled. I'm writing it from the tablet and the last time I wrote a comment from the tablet my comment appeared with shocking editing glitches.

If the editing disruptions appear again, I will repeat the same response, written from the desktop.

It was said: that the book in English brought Price and his work to mind.

"Price's contributions were largely overlooked for twenty years; he had worked only in theoretical biology for a short time and was not very thorough in publishing papers. This has changed in recent years. An article by James Schwartz published in 2000 was the beginning of the historical redress. More recently, Oren Harman's biography, The Price of Altruism: George Price and the Search for the Origins of Kindness (Norton, 2010), has received major attention, finally bringing George Price and his story to the general public. A stage play about Price 'The Altruists' by Craig Baxter won the 4th STAGE International Script Competition [14]

"

Super interesting Wikipedia entry called Price's Equation

Kindness is a human trait. Just like a big brain is a human trait.

Human traits are the result of human evolution.

As the number of inhabitants of the planet increases, so does the importance of the human trait called "kindness"

It must be assumed that without this feature humans could not survive.