In the last decade, six Israeli researchers have won the Nobel Prizes for Chemistry and Economics, but the big question is whether this is an exciting but one-off winning streak or a continuing trend of innovation and breakthrough in science in Israel?

By: Daniela Barali

Perhaps in a few decades, from the distance of time, we will be able to determine whether the "winning decade" was an exciting but one-time historical point or the beginning of a trend of innovation and breakthrough. One-off or the beginning of a trend of innovation and breakthrough

Photo: A. S. A. P. Creative Kytalpa – Fotolia.com

Israel boasts no less than ten Nobel Prize winners. There are the three Nobel Peace Prize winners, Menachem Begin, Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Rabin, and the first Israeli Nobel Prize winner, aka Shi Agnon, who received the prize in the field of literature. Four won the prize in the field of chemistry, and two in the field of economics. The six wins in these two fields occurred in a span of less than ten years, between 2002 and 2011. This fact raises obvious doubts - despite the growing complaints of the citizens and the steam about the education system, about higher education in Israel and about the lack of budgets, something good is growing here. Is it possible that someone is doing something right?

>> Galileo magazine as a gift! Click here to receive the benefit

Challenging the basic definitions

The last of the Israeli winners is Prof. Dan Shechtman, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011 for the discovery of quasi-crystals. It was a controversial discovery, which shocked the research community and forced Prof. Shechtman to wage a stubborn battle against the scientific establishment, after it initially refused to recognize his discovery and denied it.

Shechtman developed a theory according to which solid matter is sometimes organized asymmetrically. Until then symmetry was the basis of the definition of a crystal; The researchers assumed that in a solid material the atoms are compressed in crystals in symmetrical patterns that repeat themselves cyclically. Shechtman's theory, which he developed after observing through an electron microscope a crystal with a shape that supposedly contradicts the laws of nature, challenged the basic definitions of the world of research. After more than 20 years of struggles and publications, Shechtman changed the way science perceives and defines solid matter, and for his innovation he won a prize.

In a certain sense, due to his innovation and tireless pursuit of the truth, Shechtman's story distills the spirit of the Nobel Prize, which has been awarded for more than 100 years as part of the fulfillment of the will of the Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel.

Nobel was an industrialist and chemist who invented, among other things, dynamite. He watched his invention, which began to be used for the production of explosives, become a military weapon, filled with sorrow and a desire to right the wrong. To this end, he sought to establish a fund that would award prizes for extraordinary contributions to the world, or in his own definition - prizes for those who have brought the greatest benefit to mankind. The Nobel Prize is distributed annually in Stockholm, the capital of Sweden, in the fields of chemistry, physics, physiology, medicine and literature; Later (in 1969) a prize was added in the field of economics. The Nobel Peace Prize is also awarded (in Oslo, by the Norwegians). The prizes are usually awarded for various scientific, artistic and humanitarian breakthroughs, some of which changed the face of society and research beyond recognition.

A research challenge

In 2009 Prof. Ada Yonat won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry - the only Israeli woman to win the Nobel Prize so far. The award was given to her for her research in the field of ribosome structure research. The ribosome, one of the most important organelles in the living cell, is called the "protein factory", and is responsible for the production of proteins in the cell from a group of raw materials - the amino acids. Since all forms of life known to us are based on the action of proteins, ribosomes play a crucial role in the functioning of the entire organism.

Prof. Yonat and the researchers who worked with her sought to decipher the structure of the ribosome. Finding the exact structure of the ribosome has been a research challenge for many years. The ribosome is an extremely complex structure, and in order to study it, it is necessary to undergo a process of crystallization, and to leave its structure stable during the crystallographic study, conducted using X-rays. Prof. Yonat and her team were the first to overcome these obstacles, and were able to provide details and information about the structure of the ribosome and sub- Its high resolution units.

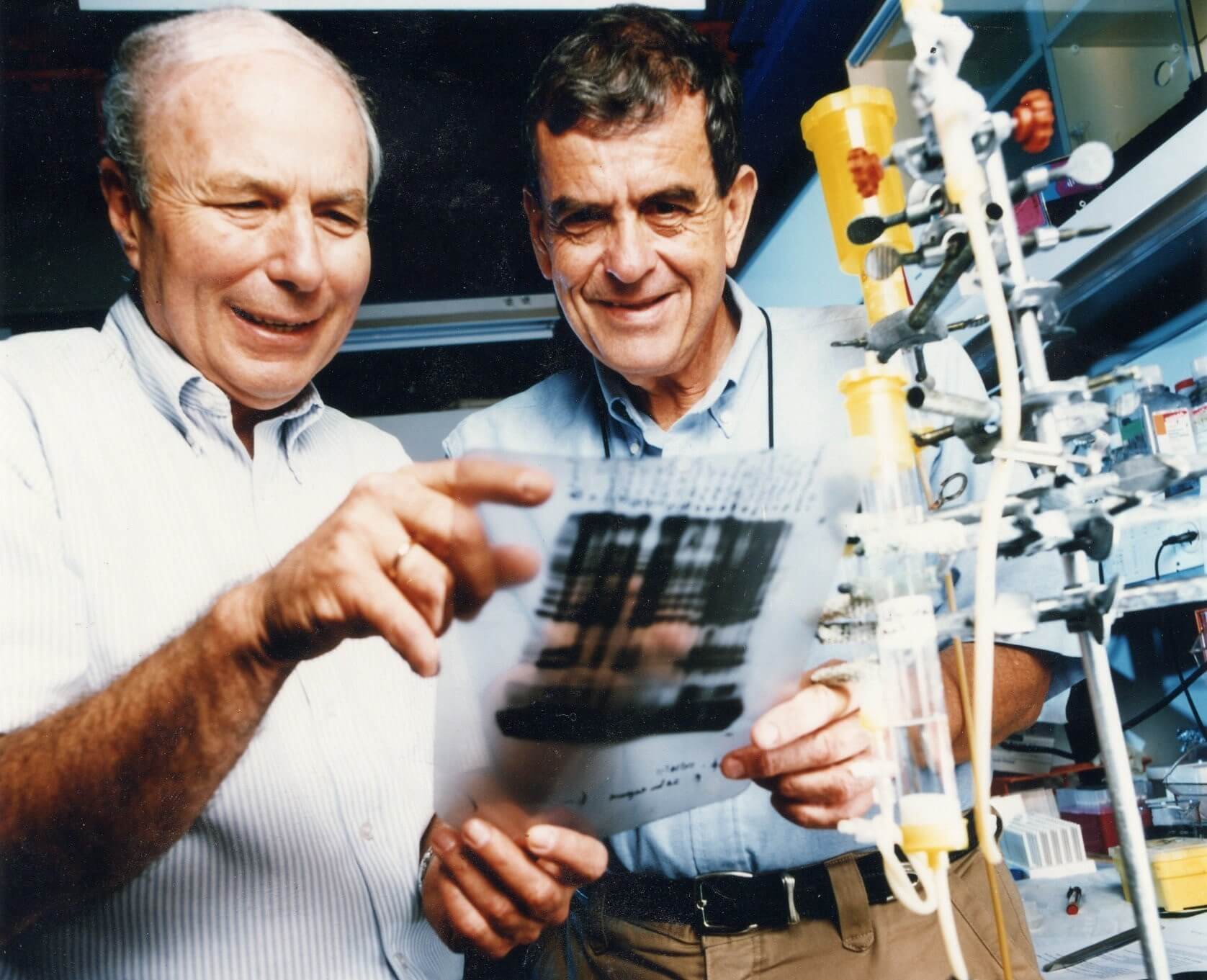

In 2004, the biochemists Prof. Aharon Chachanover and Prof. Avraham Hershko won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry (with the Jewish-American biologist Prof. Irwin Rose; Rose). The award was given to them for their research in the field of protein breakdown. In a certain sense, this is a field of research that is complementary to that of Prof. Yonat, who, as mentioned, was involved in the research of the ribosome, which is responsible for building proteins. In their joint work, which was done in part in Prof. Rose's laboratory in Philadelphia, during the sabbatical visits of the two Israeli researchers, the three were able to describe the complex process of breaking down "autonomous" proteins.

It refers to the breakdown of the cell's own proteins, as opposed to the breakdown of "foreign" proteins. They discovered that these proteins are "marked" for degradation by binding to a protein called ubiquitin. The ubiquitin system has a fundamental role in the functioning of the body, and deficiencies in its functioning are manifested in diseases. Ubiquitin is found in many of the cell mechanisms and regulates their activity - among other things, it is involved in the "quality control" process of the cell, which detects damaged proteins. The targeted research of this protein opened the door to further research in the field of cancer drug discovery. Judging by the Nobel prizes - it seems that at least the chemistry laboratories in the Israeli research institutes are functioning properly.

More on Galileo:

* Which is better: many friends on Facebook or few in real life? Let's find out

* Does anxiety make us appreciate the advice we receive more? Research reveals

Behavioral Economics

But not only the natural sciences; Mathematics and the social sciences in Israel have also produced Nobel Prizes awarded in the field of economics (there are no Nobel Prizes in the field of mathematics and psychology). In 2002, Prof. Daniel Kahneman, an Israeli-American cognitive psychologist, won the Nobel Prize for Economics, which he shared with Vernon Smith (Smith), an American professor of economics and law.

Kahneman's research focused on the field of behavioral economics and decision-making, and is considered groundbreaking research that deals with the irrational parts of a person's economic decision-making. His research work, in collaboration with the late psychology professor Amos Tversky, pointed out the gap between pure economic models, whose purpose is to predict human behavior in economic circumstances, and between actual human behavior, which is influenced by various intuitive and irrational considerations.

In 2005, the mathematician Prof. Israel Uman won the Nobel Prize in Economics for his research in the field of game theory, with Prof. Thomas Schelling (Schelling) from the University of Maryland in the United States. Game theory is a branch of mathematics and economics, within which situations of conflict or cooperation between decision makers with different interests are analyzed. The researchers in the field formulate theoretical models whose purpose is to explain and predict the strategies and choices of the participants ("the players") in the "game" - in this case the game is an economic activity.

The award was given to Prof. Uman following a study dealing with game theory, in a situation where the number of games is infinite or unknown. Uman and Schling's research helped to deepen the understanding of concepts such as conflict and cooperation within the framework of game theory, and to accurately identify the results in long-term relationships.

It is interesting that the mathematician Prof. Uman disagrees with the conclusions of the psychologists Prof. Kahneman and Prof. Tversky in the field of economic research. He challenges their conclusion that human decisions in economic circumstances are determined irrationally. According to his method, man is a more rational creature than we think, and even decisions that seem irrational at first, actually obey rational laws and internal logic. If so, the only two Israeli Nobel laureates in the field of economics disagree with each other regarding basic assumptions concerning human nature.

National pride

Every Nobel Prize winning by an Israeli raises the level of national pride. Leaders and policy makers in the Ministry of Education also like to hang on to this tall tree - "Israel produces Nobel laureates". A closer look at things yields some insights, but doesn't completely dispel the mystery surrounding the winning streak in such a short span of time.

The Israeli Nobel Prize winners in the last decade were born between 1930 and 1947. They were educated in the public education system in the forties, fifties and sixties of the last century (with the exception of Prof. Uman, who acquired his education in the United States). From the XNUMXs they worked as researchers in Israeli universities and research institutes - Prof. Shechtman, Prof. Hershko and Prof. Chachanover at the Technion in Haifa, Prof. Yonat at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot and Prof. Kahneman and Prof. Uman at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The fact that the winners are "scattered" over three different institutions bodes well for the higher education system in Israel. At the very least, it can be said that there are proper and high-quality research institutes here, and that it is possible to conduct long-term and serious research in them.

But if the success of the six is a measure of the public education system, then this measure is not valid today, decades later. It seems that the recipients of the award themselves agree with this conclusion, since four of them - Prof. Kahneman, Prof. Chachanover, Prof. Shechtman and Prof. Hershko - signed a letter indicating that they share the prevailing feeling in the country that the education system urgently needs reform and improvement.

The letter was sent to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in 2011 following the social protest, and it is signed by dozens of public figures, scientists and educators. In the letter, they implore the decision makers to change government policy and priorities and promote education, and in particular the law on free education from an early age, in the spirit of the recommendation of the Trachtenberg Committee.

But the assumption that the public education of the last century is responsible for the breakthroughs of the Israeli researchers in the last decade is far-reaching, or at least inclusive. In order to grow excellence in targeted areas, it is necessary to combine data and resources, including the allocation of budgets to research institutes, long-term encouragement for research and development on the part of the state institutions, as well as motivation, talent and a lot of determination and perseverance on the part of the researchers themselves. Did the Israeli Nobel laureates succeed thanks to the conditions provided to them by the state or in spite of those conditions? This question remains unanswered. Perhaps in a few decades, from the distance of time, we will be able to determine whether the "decade of wins" was an exciting but one-off historical point, or the beginning of a trend of innovation and breakthrough by Israeli scientists.

Daniela Brali is a writer and editor

One response

Nobel prizes are a poor measure of determining the quality of the education system. Not clear at all

As evidenced by the Nobel Prizes. When asked the genius physicist Nobel Prize winner

Enrico Fermi, "What is the trait that characterizes Nobel Prize winners? "he answerd

"I can't think of one such quality, not even intelligence."

If we take a closer look at why Israelis received the Nobel Prize and what it is

As evidence, we will find that the main feature that characterizes a considerable part of the Israeli winners is

the stubbornness Prof. Dan Shechtman's discovery was not genius, he simply recognized

A pentagram in one of the materials requested by a friend to test in the laboratory.

Pentagram symmetry is forbidden symmetry in a crystal, but Prof. Shechtman insisted

for his discovery (even when Linus Pauling was one of the greatest chemists of the twentieth century

and a winner of two Nobel Prizes came out against him). The prize in Shechtman's case is given for persistence

and refusing to submit to dictates and conventions. Ada Yonat succeeded in synthesizing ribosomes

Although the great experts estimated that this could not be done, once again the established award

On stubbornness and refusal to submit to conventions. Chechenover and Hershko simply explored a field

which was not fashionable.

Science at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century is a great science

which requires huge sums. Israel cannot compete on this front and the only chance

It is hers to compete with the island by investigating things that are irrelevant, if only because they are experts

Determined that they are impossible if because they are unfashionable. The above comments were

Regarding the Nobel Prizes in Science. Regarding Shalom, it does not seem that we have a great chance of winning

In additional awards, perhaps at the Ignoble...