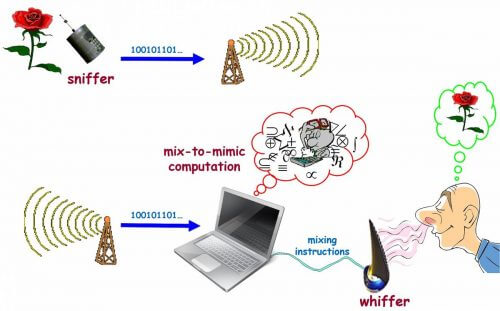

Scientists from the Weizmann Institute propose a principled way to send smells through the network, which will be based on an output device ("snuff") that contains a limited number of smells, and on a kind of "artificial nose", which will be able to create a "digital signature" of any input smell.

If tomorrow someone comes and tells us that he has managed to develop a system that can "photograph" any smell, send its digital coding on the Internet, and then reproduce it faithfully on the other side - how can we know if he is indeed telling the truth?

First, it is important to understand what is the challenge facing those who wish to develop such a system. We feel a certain smell when different substances ("perfumes") are released from some source, and reach the smell receptors in the nose and bind to them. This is how a complex neural process begins in our brain, culminating in the sense of smell. A sense of smell is often connected to memories related to a certain event, or a certain place. And if so, how is it possible (if at all) to transmit smells remotely, for example via the Internet?

Obviously, it is not possible to launch the fragrances themselves, however Prof. David Harel, from the Department of Computer Science and Applied Mathematics at the Weizmann Institute of Science, tells about a principled path that he and his friends proposed about 15 years ago, which may outline the path of those who seek to develop such a system in practice. "In nature," says Prof. Harel, "there are countless different odorants, which bind to several hundred types of odor receptors in the human nose. The processing process that takes place in our mind is very complex, and we don't seem to understand a large part of it yet. Therefore, it is clear that there is no point in talking about developing a system that will reproduce this process as much as it is. On the other hand, the experts in the study of the olfactory system believe that, in principle, it will be possible to be satisfied with an output device that contains, for example, only about 50 carefully selected odorants, in analogy to a printer that contains 3-4 ink colors, and will be able to mix them precisely and release them into the air in a controlled manner. Such a 'rabbit' would have to receive information from an input device - in analogy to a camera: a kind of 'artificial nose' - which would be able to create a 'digital signature' of some input smell. The signature will be based on the degree of attachment of the given odorant to the array of chemical receptors in the artificial nose."

However, he explains, "It is very important to understand that these two devices, some of which already exist in fact, do not solve the problem. The most complicated part of future production of an odor reproduction system is the connection between the 'camera' and the 'printer': an algorithmic method must be developed to translate a digital code of some input odor into mixing instructions for the output device, so that it mixes its 50 odors in precise compositions and concentrations, with the goal to create a mixture whose effect on human smell perception will be close enough to that of the input smell. That is, the output device will have to produce a 'correct' mixture, such that when it reaches the human nose and binds to the protein receptors there, an appropriate signal will be sent to our brain that will make us feel the smell that is 'transmitted from a distance'. This is of course an imitation. The mixture will not be the real smell in terms of its chemical structure, but it will be similar enough to it for an ordinary person to feel and recognize the smell that someone, who is far away from him, wanted to send to him."

Is this script practical? Is it possible to fulfill this principled action plan? Can we transmit smells on the Internet, as we have learned to transmit sound over a distance on the telephone, or mirrors and films through cameras, television and computers? Prof. Harel believes so, but he says: "This will probably take a long time. The missing knowledge is slowly beginning to be completed with in-depth and exciting studies."

Recently, Prof. Harel faced a related question, which is another interesting aspect of the matter. Let's say that tomorrow someone comes and tells us that he was able to solve the problem. The same person claims to have an artificial nose that "photographs" any smell, and a rabbit that receives the information digitally and disperses a mixture that creates the familiar feeling of the original smell in the person. How can we know if he succeeded in this, and that the system is indeed "correct"?

Here Prof. Harel recalled the Turing Test - a conceptual test proposed in 1950 by the father of computer science, Alan Turing, to differentiate between a person and a computer, or between a person and artificial intelligence. The test is structured so that in one closed room sits a person, in a second closed room is located the system whose designers attribute artificial intelligence, and in a third closed room sits the examiner. The examiner can communicate with the machine and the human examinee, ask them questions, talk about today's affairs, philosophy, technology, sports, and the like. If during these conversations he fails to distinguish who is the person and who is the machine - then the technological system can indeed be considered to have artificial intelligence. A Turing-like test is not suitable for the current problem, Prof. Harel claims, mainly because we are trying to test the ability to reproduce a familiar human sense of smell, but humans do not have a language in which they can describe any smells to each other distinctly.

That's why he offers Another test, which involves a challenging team, whose job it is to try to disprove the claim of the builder of the system being tested, and a neutral testing team. The main idea is to combine scents in their natural environment, using sound and mirror recording. The challengers prepare a large number of short videos filmed in different environments, such as a mafia, a jungle, a laboratory, a musty attic or a blooming orchard. For the purpose of examining the ability of the system to reproduce the sense of smell faithfully, the examiners will be given several "identification procedures". In such an "arrangement" they will be given about ten video clips from those that the challengers prepared, as well as a smell that matches one of them, and they will be asked to identify the audiovisual environment that matches the smell.

In order to avoid challenging situations that cannot be identified (such as, for example, a video clip of an open field prepared with the back of the camera showing an opening to a cave that smells strongly of mold), it is necessary to refine the test so that we never require the artificial smell to do what we cannot do for the smell the true. This is done by means of what Prof. Harel calls "conditional identification systems", where the examiner team is made up of two groups, who watch the same video clips, and receive a scent that corresponds to one of them. But the examiners in the first team receive the real odor molecules collected at the place where the video was prepared, while the others receive the odor that was "transmitted over the network", that is, the one that was artificially composed by "photographing" the odor using the system and algorithm that gave the mixing instruction to the "sniff". The conditional requirement is that in any case where the members of the first team are successful in the identification, the members of the second team will also be successful. And if this result is obtained several times, for each challenge prepared by the challenging team, then it can be said that the system is indeed capable of reproducing (and then of course also transmitting and transmitting on the Internet) a recognizable and recognizable human sense of smell.

One response

In my opinion, there is another way to identify the different smells and that is a neurological way.

It seems that each smell activates a characteristic electrical response in the brain that is unique only to it.

There may even be several basic reactions to basic smells, and the other smells

They are combinations, in different bones, of the reactions to the basic smells.

If the study succeeds in accurately characterizing all the electro-neurological responses

The difference to the different scents, it will be possible to create a "catalogue" that will link the scents

the different ones and the different electro-neurological responses to smells, and thus identify

the smells according to the electro-neurological reactions that will remain in the brain activity.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::: Easy to propose - hard to prove ::::::::::::::::: :::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::