The system may be used to perform thousands of tests to identify viruses, as well as for studies designed to find ways to contain them

Scientists who seek to develop tests to identify viruses, or drugs or a vaccine against a virus, are required, first and foremost, to know the structure of the virus being studied. But of course, when it comes to violent viruses, working with real viruses involves a considerable risk. Prof. Roi Bar-Ziv, staff scientist Dr. Shirley Shulman Dauba, (then) research student Dr. Ohad Wanshek and research student Yiftah Divon in the Department of Chemical and Biological Physics at the Weizmann Institute of Science describe how they faced the challenge in an original way. They created artificial cells - a kind of micrometric dimples - that were "carved" in a silicon chip. At the bottom of the "dimples" of the artificial cells, the scientists determined dense DNA strands. In the perimeter of the "cells", they placed a sort of "layers" of receptors that bind the proteins that the system produces. At the beginning of the process, the scientists injected into the artificial cells a solution that contained the molecules and enzymes that "read" the genetic information in the DNA strands and produce proteins according to them. In the next step - which takes place without human intervention - the receptors that the scientists placed around the perimeter of the artificial cells, bind one of the proteins of the virus created in the cell. Later, the other proteins of the virus combine with each other and together form the structures that the scientists sought to create - in this case, small parts of a special type of virus that attacks bacteria ("bacteriophages"). The research findings are published today in Nature Nanotechnology.

"We discovered," says Prof. Bar-Ziv, "that we can control the assembly processes, their efficiency and the products that will be assembled in our artificial cells - through careful planning and design of the geometric structure of these 'cells.' In addition, changes in the locations of the genes and their various clusters determine, in fact, which proteins the cell will produce, and subsequently, what it will assemble and produce from them." Adds Dr. Wanshek: "The fact that these are 'micrometric artificial cells' allows us to place a huge number of artificial cells on one chip, and by means of a different design, cause different cells to perform different tasks in the same 'run'."

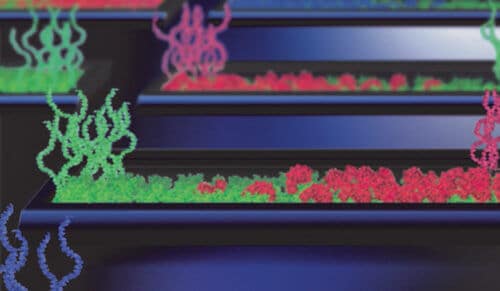

The artificial cells: micrometric dimples that were "carved" in a silicon chip

These features of the system developed by the institute's scientists and the ability to simultaneously create many small and different parts of viruses may allow scientists, all over the world, to create and test different drugs and vaccines against it. "These experiments", says Divon, "which will be based on synthetic parts - and not on components of the real virus - will be carried out at a particularly high level of safety". "Another possible future application of this system," adds Dr. Shulman-Dova, "is the performance of thousands of medical tests at the same time, in a fast and efficient manner."

Scientists from the Max Planck Institute in Potsdam, Germany and the University of Minnesota in the USA contributed to the research.

More of the topic in Hayadan:

One response

Very interesting, just reminds me a little too much of Theranos...