Biological warfare / The anthrax scare in the US increases research budgets

by Tamara Traubman

The anthrax envelopes that were mailed to the residents of the United States after the terrorist attack on September 11, turned anthrax from a marginal bacterium in biological research into the "star" of the laboratories. Studies on it appear in the most prestigious scientific journals in the world, and security forces are allocating more and more budgets to the study of the deadly bacteria.

Such a study, funded by the US Department of Defense - and published yesterday in the scientific journal "Nature" reported that researchers have developed a new type of antibiotic, which may be used simultaneously to treat humans infected with anthrax and as a detector that locates areas infected with the deadly bacteria. The new antibiotic is based on the use of the main natural enemy of anthrax: "bacteriophage" - the virus that kills bacteria. The development of the method, however, is not yet complete; And according to one of the researchers, it will take at least three more years before humans can use it.

The type of anthrax sent to people in the United States - the Ames strain - can be treated with ciprofloxacin antibiotics. However, there is a fear that organizations or countries will develop new anthrax strains, which are resistant to the conventional antibiotic drugs. In addition, more and more bacterial species are developing resistance to an increasing number of antibiotic drugs. Anthrax, scientists say, may naturally develop resistance to conventional drugs.

"We know today that anthrax is a real threat," said the head of the team of researchers, Dr. Vincent Fischetti of Rockefeller University. "A bigger threat is the drug-resistant strains of anthrax. These may be created naturally and also by terrorists. Therefore, alternative strategies to combat these dangerous strains are needed more than ever."

Bacteriophages, or phages for short, are one of the most common life forms on Earth. They are everywhere full of bacteria. The phages inject their genetic cargo into the host bacterium, replicate themselves by the hundreds - then tear the cell wall of the bacterium and move on to the next host bacterium.

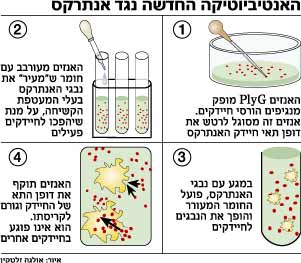

When the anthrax bacterium is in an unfriendly environment, it becomes a spore - a kind of state of dormancy, in which the anthrax is wrapped in a hard shell. To break this envelope, the researchers used a substance that causes anthrax to "wake up". To this substance they added an enzyme, known as PlyG. The enzyme allows the bacteriophage to tear the bacterial cell wall. The "stimulating" substance overwhelms the anthrax and makes it think it's time to wake up. But before the bacterium was given a chance to realize that it was being fooled, the enzyme starts working and kills it almost instantly.

"A few drops of the compound are enough to destroy, almost immediately, a test tube full of anthrax bacteria," Schutz said, "and this includes the Ames variety." Dr. Schutz calls the enzyme a "targeted killer." Since it is derived from a phage that only attacks anthrax bacteria, the enzyme will only attack those bacteria, and not other bacteria.

"We tested the enzyme on many species of bacteria, including other bacteria from the anthrax family, and found that it did not touch them," said Fischetti. "It is helpful, because this type of treatment will not kill bacteria that are beneficial to our body and thus the drug will have fewer side effects."

However, the new compound has a drawback: it must be taken shortly after exposure to anthrax, before the bacteria's lethal levels develop. The researchers have not yet finished testing the effectiveness and safety of the compound on animals.

The compound can also be used to quickly locate areas infected with anthrax, a procedure that today takes several days. "The bacteria that are cleaved by the enzyme, secrete another enzyme, which can be detected by staining them with phosphorescent substances and a manual light meter within minutes," explains Fishti. However, Fishti added, that "this is only the basis. To make this an effective and easy-to-use detection method, further research is needed."

Scientists believe that the likelihood that the anthrax will develop resistance to the new compound is lower than the likelihood that it will develop resistance to the existing antibiotic drugs. Dr. Steven Lepele, from the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, says that the reason for this is that in order for the anthrax to develop resistance to the enzyme, "it must change the cell wall, this is a very basic and fundamental change, and even if it succeeds it will take a long time."

"The phages have been in the world for billions of years," says Schutz. "In these years of evolution, they have improved and become better bacteria killers. As a result, the bacteria will have to invest a lot of effort to understand how to rebuild a basic structure in their cell wall." According to him, what he and his colleagues actually did in the research "is to use the extensive experience gained by the phages".