A team of researchers from Johns Hopkins University who excavated at the edge of a coal mine in India, managed to fill a large gap in scientific knowledge of the evolution of the group of mammals that includes horses and rhinoceroses.

A team of Johns Hopkins University researchers excavating at the edge of a coal mine in India have succeeded in filling a large gap in scientific knowledge of the evolution of the mammal group that includes horses and rhinoceroses, a group that most likely originated in the Indian subcontinent when it was still an island before colliding with Asia. The researchers published their findings in the November 20 issue of the online journal Nature Communications.

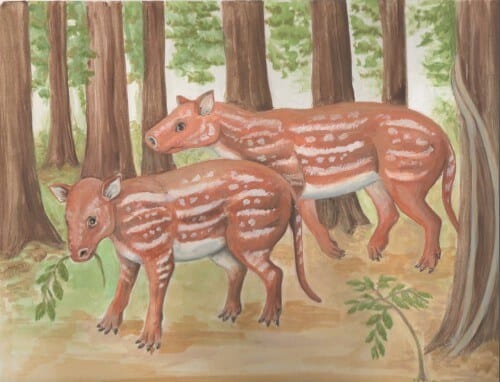

Modern horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs belong to a biological group called Perissodactyla, also known as "odd-toed ungulates," which, as the name suggests, have an odd number of toes on the members of the group's hind legs, as well as a unique digestive system.

"Although paleontologists have found remains of Perissodactyla since the beginning of the Eocene era, about 56 million years ago, their early evolution remains a mystery," says Ken Rose, professor of functional anatomy and evolution at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Rose and his research team have been digging for years in the Big Horn Basin in Wyoming, but in 2001 he and colleagues from India began investigating Eocene sediments in western India that suggest fossil perissodactyls and several groups of other mammals may be found in an open-pit coal mine northeast of Mumbai. They uncovered a rich vein of ancient bones. Rose says he and his colleagues have obtained funding from the National Geographic Society that has allowed them to send a research team to a mine site at Joart in the remote western part of India for two weeks at a time every year or two for the past decade.

The dig yielded what Rose calls a "treasure bloom" of teeth and bones that the researchers took with them and scanned when they returned to their laboratories. Of these, more than 200 fossils turned out to belong to animals named Cambaytherium thewissi, which are almost unknown. The researchers dated these fossils to 54.5 million years old which makes them slightly younger than Perissodactyla. The findings allow a glimpse of what appears to be the common ancestor of all species in the Perissodactyla family. "It exhibited many of the features of Cambaytherium, such as the teeth, the number of sacral vertebrae, and the arm and leg bones that appear to be intermediate between Perissodactyla and more primitive animals," Rose says. "This is the closest thing we've found to a common ancestor of Perissodactyla."

These and other findings at the Jowart coal mine also provide clues about India's separation from Madagascar and its eventual collision with the Asian continent as the Earth's tectonic plates shifted.

In 1990, two researchers, David Krause and Mary Maas of Stony Brook University, published a paper raising the possibility that several groups of mammals that appeared in the early Eocene, including primates and ungulates with even and odd numbers of toes appeared in India during isolation. Cambaytherium is the first solid evidence supporting the idea, but according to Rose, the story is not simple.

"Around the time when the Cambaytherium lived, we think that India was an island, but it also had primates and rodents similar to those that lived in Europe at that time," he says. "One possible explanation is that India passed near the Arabian Peninsula or the Horn of Africa, and there was a land bridge that allowed the animals to cross, but Cambaytherium is unique and suggests that India was indeed isolated for a while."

Rose said his team was "very fortunate that we discovered the site and that the mining company allowed us to work there," though he added, "It was frustrating to know that countless fossils could have been trampled by heavy mining equipment." When the coal mining ended, the miners covered the site, and he said his crew members began digging in other mines in the area.

For the announcement on the Johns Hopkins University website

2 תגובות

The translation of the foreign name is "from horseshoe items". The word odd in English here means an odd number (single) and not "strange"

clarification

ungulates - ungulates.

Perissodactyla - having an odd number of fingers (the meaning of the word odd in this context).