Although Europa is thought to consist of a frozen crust of water ice, protecting a salty underground ocean several kilometers deep, researchers * So concluded researchers who met last week to begin preparing the ground for NASA's planned Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter .

Jeff Hecht, New Scientist (translation: Dikla Oren)

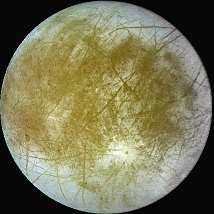

Jupiter's moon Europa is not a water paradise and a perfect place to search for extraterrestrial life. On the contrary, Europa may be a corrosive hothouse of acids and hydrogen oxides. That's the conclusion of researchers who met last week to begin preparing the ground for NASA's planned Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter.

Almost all the information we have about Europa comes from the Galileo spacecraft, which completed its mission to study Jupiter and its moons. Shortly thereafter, NASA smashed it into Jupiter in 2003.

Although Europa is thought to consist of a frozen crust of water ice, protecting a salty subsurface ocean several kilometers deep, researchers, relying on the latest measurements, say that the light reflected from the icy surface of the moon carries the spectral fingerprints of hydrogen oxides and other strong acids, possibly Even if their acidity reaches pH 0.

However, the researchers are not sure whether it is only a thin layer that contains the chemicals, or whether they come from the depths of the ocean. The hydrogen oxides are likely on the surface, as they form when charged particles, trapped in Jupiter's magnetosphere, hit water molecules on Europa.

However, parts of the surface appear to be rich in water ice, which contains what appear to be acidic components. Robert Carlson of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, estimates that it is sulfuric acid.

Carlson says that it is possible that up to eighty percent of the ice on the surface in some areas is concentrated from sulfur oxide concentrations. He suggests that it is a mantle of sulfuric oxide, formed by shelling the surface with sulfur atoms, originating from the volcanoes of Io, another moon of Jupiter.

Other scientists think based on the results from recent measurements, that the acid is coming from Europa's ocean. Tom McCord of the Planetary Science Institute in Winthrop, Washington, notes that the greatest concentrations of the acid are in areas where the state of the ice suggests that ocean water broke through the ice and froze.

McCord thinks that the acid on the surface originates from salts from the underground ocean, mainly magnesium and sodium sulphide. Strong radiation fluxes caused chemical reactions, he says, that left an ice crust, which contains a high concentration of sulfuric acid and other sulfuric components.

"Europe hides an island in its ocean", he says. If the sulfur salts on the surface came from ocean water, it may be composed of brine saturated with sulfuric acids.

This means bad news for the chances of finding life there, as strong acids tend to break down organic molecules. However, this does not mean that the chance is slim, there are species of bacteria on earth that thrive in environments with an acidity level of zero pH.

Another blow to researchers hoping to explore the possibilities of life in the moon's ocean comes from another direction. Hints have been discovered that the surface of Europa is lined with hills. Paul Schenck from the Lunar and Planetary Institute reports that a dark area on the surface of Europa is actually a 350-meter-high valley, located near a 900-meter hill, meaning the height difference is 1250 meters. Schenck calculated that in order for this structure to be stable, the ice layer must be about ten to thirty kilometers thick. This is a thickness that will deter any probe from drilling through it.

However, researchers will probably not derive any more knowledge from the information provided by Galileo. Its measurements cover only a tiny fraction of Europa's surface, and most of the details have been blurred by background noise and low resolution.

"I don't think we'll get a better answer until we get back there with better spectrometers, better resolution and maybe a lander," McCord told New Scientist. He must think about how to do exactly that, as part of being a member of the scientific team of the JIMO (the spacecraft intended for the moons of Jupiter), which should be launched in 2012.

"If the surface is made of sulfuric acid, landing shouldn't be a problem, as long as the ice stays frozen," he says. If it turns into a liquid, however, the acid may be strong enough to eat away at most materials used to build spacecraft. This fact will surely delay the proposals to land a probe, which will melt the ice and explore the ocean beneath it.

Link to the original article in New Scientist

Yedan was right

https://www.hayadan.org.il/BuildaGate4/general2/data_card.php?Cat=~~~766843595~~~19&SiteName=hayadan