Scientific research has dated a famous Monet painting

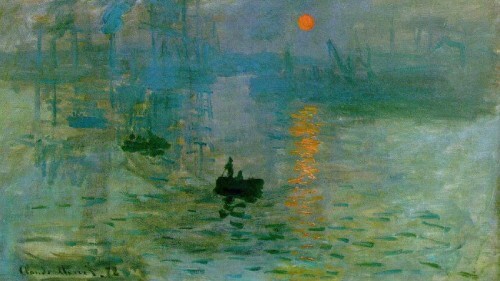

Louis Leroy was not one of the prominent artists of the 19th century. He wrote plays, was a painter and also engaged in engravings, but he got most of his publication not as an artist but rather as an art critic, mainly in the satirical magazine "Le Charivari" (a word that means loud music, or riot) that was printed in Paris for more than 100 years . In April 1874, Larroe visited an exhibition of some relatively young artists, who were not embraced by the art establishment and academia, due to their unacceptable style of painting and sculpture. Since it was not possible for them to present their works in the official exhibitions, the artists founded their own exhibition, and even invented a group name for themselves: "The Company Ltd. of Painters, Sculptors and Engraving Artists". One of the pictures that made the most impression in the exhibition was a painting called "Impression, Soleil Levant", by Claude Monet. The painting shows a small boat in the water, against a hazy background of a harbor and ships' masts, a blue-yellowish-greenish sky, as well as a blurred band of the reflection of the rising sun in the sea water. The use of bright colors and blurred drawing of objects, while ignoring the clear boundary lines of each object in the painting, was laughable in the eyes of the art critics of the time. Many 19th century art consumers considered such paintings by Monet and his colleagues to be unfinished works - more of a sketch of a picture than a complete picture. The viewer gave expression to these feelings in the review he published in his newspaper, referring to the painting's name: "An impression - I was sure of it. I told myself that since I was prescribed, there had to be some impression on him... and what freedom, and what skill! A new roll of wallpaper is more complete than the same seascape." Later it turned out that this line of criticism was ultimately the pinnacle of Leroy's fame: the art stream of Monet and other participants in the exhibition (including Renoir, Pizaro, Sisley, and Degas) received the name "impressionist stream" thanks to the review list, or in dialect "Impressionist" – impression). Despite the criticisms and institutional neglect at the beginning, Impressionism was one of the most prominent artistic currents at the end of the 19th century, and had a great impact deep into the 20th century, not only on visual art, but also on literature and music.

Sunrise or sunset?

Claude Monet himself later told why he chose this name for the picture. In an interview from 1898, he said that he had submitted to the exhibition a painting he had done in Le Havre (Le Havre, a port city in northwestern France, on the shores of the Le Mans Canal), and then he would be asked to name the picture. "This is a picture I drew from my window," he said, "a hazy sun and some masts of ships. It was not possible to define it as a landscape picture of Le Havre, so I simply said that it should be called 'impression'." As mentioned, the picture left a strong mark on the history of art, but it also left art lovers with an unsolved mystery. Next to the artist's signature at the bottom of the painting, the number 72 is written. However, in the catalogs published later it is written that the year of creation of the picture is 1873, because as far as is known, Mona worked in Le Havre in the spring of that year. Art experts not only did not attach much importance to the number Monet wrote on the picture but also did not take seriously the name he gave it and claimed that it was a sunset, not a sunrise. Monet himself did not address the issue, and the mystery was not solved until his death in 1926, at his estate in Giverny, where he spent most of the last decades of his life painting the objects most associated with his work: water lilies. In fact, the mystery remained until recently, when Donald Olson from the University of Texas entered the picture.

Heavenly Intelligence

Olson is a professor of astrophysics, who has studied phenomena such as radiation from black holes and galaxy dispersion models. However, in recent years he is increasingly involved in solving historical mysteries with the help of physical data such as the movement of celestial bodies. For example, Olson tried to find out why American marine ships that stormed the shores of Tarawa Island in World War II got stuck on coral reefs about half a kilometer from the shore. The marines were forced to abandon them and wade through the water to the beach itself, exposed to heavy fire, and hundreds of fighters were killed. When Olson examined the astronomical data, he discovered that when he landed on the island, in November 1943, the moon was in the farthest part of its orbit from Earth, and because of this the tide was relatively low, and the heavy boats were unable to pass the reef. He also used a similar analysis in the study of a much earlier naval landing, and he was able to determine the exact location where Julius Caesar's forces anchored on the shores of Britain in 55 BC, and also the exact date (23.8). In another study, Olson stated that the distance of the moon contributed to the sinking of the Titanic. At the time of the sinking (April 1912), the moon was at its closest point to Earth in a period of more than 1,000 years, which caused strong currents and a high concentration of glaciers in the path of the giant ship.

Another hobby of Olson's is exploring issues in art with the help of astronomical instruments. For example, he tried to find out the meaning of the strange color of the sky in Edvard Munch's famous painting "The Scream". Munch himself said that the idea for the painting came to his mind during a trip to Oslo, when the sky was red as blood and engulfed in flames. Many art scholars saw this as an artistic metaphor, but Olson did not accept the explanation. He found evidence that the sky in many parts of Europe was colored in strange hues following a powerful eruption of a volcano in Indonesia in 1883, and it is possible that the majestic sight was still etched in Munch's mind when he painted "The Scream" a few years later. In another study, he and his students found the house where Vincent Van Gogh lived in Auvers-sur-Oise, France, after the view from the house shown to them did not match the view of the sky as Van Gogh had painted from his window. Olson describes many of the historical and artistic mysteries that occupied him in the book Celestial Sleuth, which was published this year.

Also because of the wind

When Olson heard about the mystery regarding the date of painting of the picture "Impression, Sunrise", he decided to get into the thick of it. He studied the subject, then began researching the appearance of the city of Le Havre in the early 70s. He analyzed hundreds of maps of the city from the time, and photos of the harbor area, crossed it with historical information about Monet and was able to identify the hotel where the painter lived, and also the room from which he painted the view of the harbor. Armed with this information, which allowed him to determine the painter's angle of view, Olson examined the angle of the sun in the picture, and immediately ruled out the possibility that it was a sunset. He concluded that the picture depicts the view from Monet's window 19-30 minutes after sunrise. To narrow down the range of dates for determining the date of the painting, Olson took advantage of the fact that the port of Le Havre was quite shallow at the time, and the large ships visible in the picture through the morning mists could only enter or leave it at high tide. With the help of a computer program he developed, Olson determined the times of high tides and low tides in the area during the said period, and when he crossed them with the time of sunrise, he got 20 possible dates for the painting in 19 and 1872, all in the months of January and November. The next step was an examination of the weather records from the time. The detailed historical record allowed Olson to delete from the list of dates very cloudy days, when it was not possible to see the sun at sunrise, as well as days of rough seas that do not coincide with the calm water in the painting. In addition, the direction of the billowing smoke in the port indicates an easterly wind that was blowing at the time of the painting. Weighing all this data left only two possible dates: 1873 or 13.11.1872. At this point, Olson returned to historical writings about Monet's work, and from a careful analysis of them he realized that of the two possible dates, the earlier is the correct one, because Monet was probably not at Le Havre in January 25.1.1873. The conclusion was that the sunrise that left its mark on all Impressionism was that of Boker Wednesday, November 1873, 13.

A robbery without a break

The full story of the dating of the picture is published in the brochure of Monet's exhibition opening this month at the Musée Marmottan-Monet in Paris. "Impression, Sunrise" hangs in the museum permanently... almost. On October 28.10.1985, XNUMX, five masked men entered the museum. They threatened the guards and visitors with guns and escaped in broad daylight with nine works of art, including the image that is the focus of our story.

Anonymous information received by the police led to the arrest in Japan of a Yakuza (Japanese criminal organization) man who spent five years in a French prison for drug smuggling. It turned out that during the prison he changed his criminal tastes, and switched from drugs to art theft. In his house is a catalog of the Marmottan-Monet Museum, and in it are marked exactly the same nine pictures that were stolen from him. If that wasn't enough, the police also found two pictures on him that were stolen from another museum in France a year earlier. His investigation led to the arrest of his two accomplices, French criminals who were in prison with him. Five years after the robbery, the stolen photos themselves were found - in a villa in Corsica. The members of the gang apparently tried to sell the pictures in Japan, but no one dared to purchase the works from them because it was clear to everyone that these were stolen pictures, which no collector would be able to display. It can be assumed that the Parisian museum has since upgraded its security system. But if someone steals Monet's famous picture, even if he can't sell it, he can certainly take comfort in the fact that he will know with great precision the date of its creation.

In the same topic on the science website:

The sky in Munch's painting The Scream is red because of a volcanic eruption

Impressions from an exhibition of paintings by artists who came from Darwin

Wall paintings from the 19th century were discovered in a monastery in Jerusalem

3 תגובות

Why was it necessary to perform such complicated calculations if he knew exactly the location of the room from which the view was visible? Isn't it easier to check which direction the room faces (east or west) and based on that determine if it was sunrise or sunset?

Olson also researched the opening scene of "Hamlet" and claimed to have located the supernova explosion that inspired Shakespeare's words to the guards of Elsinore Castle describing a particularly bright star.

http://www.haaretz.co.il/misc/1.811746

But the article in "Haaretz" was published 12 years ago, so what's new now?

Interesting and well written article. Thanks!