Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science and Tel Aviv University have recently applied their own sophisticated technologies to examine how stone tools were produced at the end of the Paleolithic period found in Kesem Cave near Rosh Ha'Ein

Our ancestors not only made fire, they also used it to develop sophisticated tool making technologies. Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science and Tel Aviv University have recently applied their own sophisticated technologies to examine how stone tools were produced at the end of the Paleolithic period found in a cave near Rosh Ha-Ein. Their findings are published today in the scientific journal Nature Human Behavior It is pointed out that already about 300 thousand years ago the ancient man knew how to use controlled heat at different degrees of heat to create different types of tools.

Exactly 20 years ago, in October 2000, Prof. Avi Gofar and Prof. Ran Barkai from Tel Aviv University discovered the Kesem Cave - where remnants of the Hoshelo-Yabrud culture from 200 to 420 thousand years ago were preserved. These ancient relatives of modern humans lived in a magic cave and left behind tens of thousands of tools, including many blades - unique and innovative stone tools that were hewn from flint and used for various activities, including hunting donkeys. Dr. Philippa Natalio from the Scientific Archeology Unit at the Weizmann Institute of Science and his research partners wondered whether, in order to prepare the blades and other tools, the cave dwellers used fire to improve the chipping ability of the flint blocks. So far, clear evidence of the controlled use of heat for these purposes has only been found in much later cultures - less than 100 thousand years ago.

"The first challenge in trying to understand whether flints underwent a structural change as a result of exposure to fire is the fact that the structure of flint changes from place to place and even from rock to rock, according to the geological conditions in which it was formed," explains Dr. Natalio, "in addition, the evidence of applying heat to solid rock is usually Microscopic to invisible". To face these challenges, Dr. Natalio and the post-doctoral researcher Dr. Aviad Agam, who specializes in prehistoric archaeology, turned to Dr. Ido Panaks, an expert in the technique known as Raman spectroscopy in the Department of Infrastructure for Chemical Research at the Institute.

Before approaching the archaeological finds themselves, the scientists collected flints from areas near the Magic Cave and other places throughout the country, heated them in an oven at different and diverse temperatures, and then examined them in Dr. Pankas's spectroscopy laboratory. The scientists were indeed able to reveal the structure of the flint stones down to the molecular level, but the amount of information was too much for it to be possible to draw any conclusions from them. To this end, the researchers turned to Dr. Ido Azuri from the Bioinformatics Unit. Although this is not his usual biological research, Dr. Azuri was able to find patterns in the findings obtained from the "baking" of the stones - and through machine learning methods he reproduced the degrees of heat that were applied to each of the flint blocks.

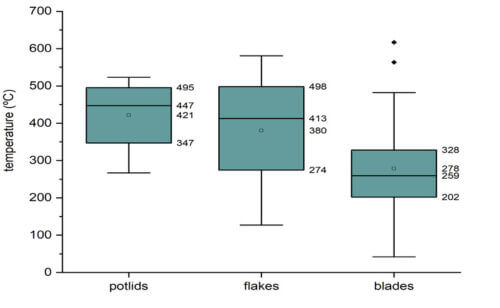

In the next step, the scientists applied the spectroscopic analysis and machine learning to randomly selected samples from among the thousands of finds excavated in Kesem Cave. The scientists revealed three different degrees of heat that were applied to three different types of archaeological items: the first type - fragments that sputtered spontaneously as a result of flint being exposed to direct fire at a temperature of up to 600 degrees Celsius. The second type - splashes of flint stones created as part of the chiseling work of the cave dwellers; These splashes were created in a relatively wide temperature range, and the third and most important type of all - the blades - large and elongated, knife-like tools, with one sharp edge and a dull second edge that can be gripped. Unlike the flint splashes, the blades were created from raw material (flint) that was heated to lower temperatures (300-200 degrees) and in a much smaller temperature range.

"We do not know how the cave dwellers learned the skill of making tools or how they even managed to control the process, but the findings clearly indicate a consistent technology of producing blades from raw materials treated with controlled heat, which is different from the way other tools are produced. This fact points to knowledge-based planning," says Dr. Natalio, and Dr. Pankas adds: "This is technology, just as our cell phones and computers are technology; A technology that allowed our ancestors to survive and prosper."

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- First evidence of regular use of fire in Kesem Cave from 300 thousand years ago

- Archaeologists from Tel Aviv University revealed that a modern man who lived in a magic cave 400-200 thousand years ago developed modern technologies for their time

- The oldest modern human remains were discovered in a cave near Rosh Ha'Ain

- Man stored food long-term as early as 400 years ago

3 תגובות

What interests me is the process of building the reputation of Merat Kesem as the "first center of technology" in prehistory... Every article about the cave emphasizes the "modernity" of its inhabitants, the "new technologies", etc.

I do not rule out the possibility of the existence of (relative) geniuses also among the animals and certainly among the hominids, but it is improbable to assume that the cave population always enjoyed, in the span of 230,000 years of inhabiting the cave, (almost 10,000 generations!) any superiority, genetic or cultural, over other sites of the same periods.

What is really happening is that the research processes of the cave are apparently very "modern and technological", and the intellectual advantage belongs to the group of contemporary researchers who discover things that were hitherto unknown, and not to the inhabitants of the cave for thousands (!) of their generations.

The article raises many difficulties that cast doubt on its conclusions.

What benefit did the tool makers derive from heating the stone?

Such tools were also created 2.5 million years ago. Long before fire was used.

Researchers of the ancient stone industry know how to create stone tools in the ancient style without using fire. The authors of the article do not tell us if the heating marks were not created due to the small fragments being left at the place of the fire, while the heat marks on the blades could have been created as a result of fires that were lit at other times at the same sites.

Since the creation of sophisticated flint tools preceded the use of fire, the theory of the authors of the article is far from established.

Hot!!