The researchers were able to reduce the risk of developing cancer metastases following the treatment from 52% to only 6% in model animals

A new development by Tel Aviv University may greatly optimize chemotherapy treatment among breast cancer patients, and reduce the risk of developing cancer metastases following the treatment from 52% to only 6%. As part of the study, which was conducted on model animals, the researchers identified the mechanism that produces the inflammatory environment in the area of the body treated by chemotherapy, and found that by combining an anti-inflammatory factor in the chemotherapy, metastases can be prevented.

The study was conducted under the leadership of Prof. Neta Erez from the Department of Pathology in medical school and the members of the laboratory team: Leah Montran, Dr. Nur Erscheid, Yael Zeit, and Yaela Sharaf, as well as in collaboration with Prof. Iris Barshak from the Sheba Medical Center, and Dr. Amir Sonnenblik from the Tel Aviv Medical Center (Ichilov). The article was published in the prestigious journal Nature Communications, and was funded by the European Community (ERC), the Cancer Society and the Emerson Foundation for Cancer Research.

"In many cases of breast cancer, the tumor is surgically removed, and then the patient is given a series of chemotherapy treatments, with the aim of eliminating cancer remnants that the surgeon was unable to remove or that have already spread throughout the body," explains Prof. Erez. "Chemotherapy does indeed kill cancer cells, but often it also has unwanted side effects. One of the most serious of them is the creation of damage in healthy tissues, and inflammation which, paradoxically, may help remaining cancer cells to develop metastases in other organs of the body. We wanted to examine how this happens, and try to find a solution to the deadly phenomenon."

As part of the study, the researchers created a model of animals with breast cancer, which went through a course similar to that of sick women: surgical removal of the primary tumor, followed by chemotherapy and follow-up to detect metastatic recurrence of the disease as soon as possible. The researchers followed the condition of the animals, and the findings were alarming: in a significant number of them, metastases developed in the lungs - at a rate similar to the development of metastases in the control group.

The opposite result of chemotherapy

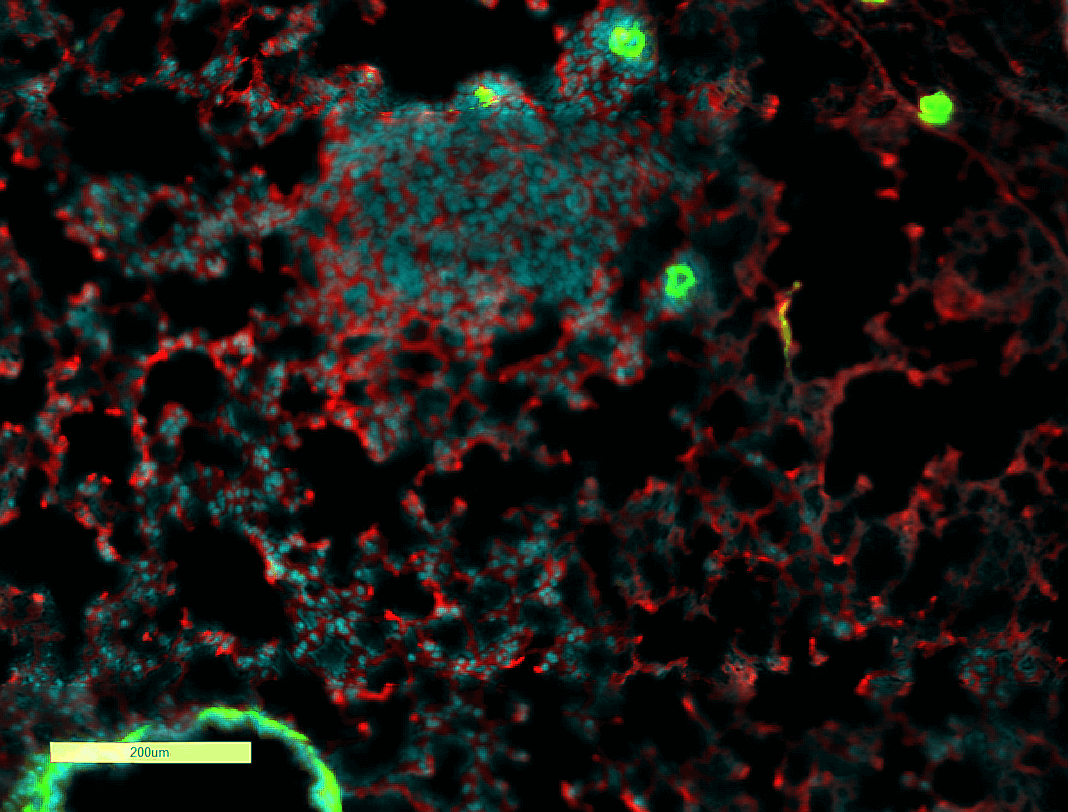

Now the researchers wanted to follow the development process of the metastases. To this end, they examined the condition of the lungs of the model animals in an intermediate stage - when hidden micro-metastases may have already formed in them, but they cannot be detected even with advanced imaging methods such as CT. "In humans, this period between the chemotherapy treatment and the appearance of detectable metastases is a kind of 'black box,'" says Prof. Erez. "In the laboratory animals, we were able to check what was really happening there, and we found a significant mechanism that was unknown until now: the chemotherapy treatment triggered an inflammatory reaction in the fibroblasts, which are the connective tissue cells of the lungs, and these cells summoned immune cells from the bone marrow to the scene. In this way, an inflammatory environment was created in the area that actually supports the development of the micrometastases, and they turned into actual cancerous metastases. Bottom line: chemotherapy, which was designed to fight cancer, actually achieved the opposite result."

The researchers identified the mechanism by which the fibroblasts recruited the cells of the immune system and then "educated" them to help the tumor. "We discovered that in response to the chemotherapy treatment the fibroblasts secreted proteins called 'complement proteins'. These are proteins that mediate and increase inflammation, partly by recruiting white blood cells of the immune system to areas where there is infection or tissue damage (a process known as chemotaxis). When the immune system cells reached the lungs, they created an inflammatory environment that supports the cancer cells and helps them develop."

Adding an anti-inflammatory factor to the chemotherapy treatment

As a countermeasure, the researchers decided to combine the chemotherapy treatment with a drug that inhibits the activity of the complement proteins, with the aim of preventing the unwanted effect of the treatment. The results were extremely encouraging: the proportion of model animals that did not develop metastases at all after treatment increased from 32% to 67%; And the proportion of those who developed metastases in many foci in their lungs dropped from 52% with standard chemotherapy, to 6% with chemotherapy plus the inhibitor of inflammation.

"In our research, we were able to discover the mechanism behind a serious problem in the treatment of breast cancer patients: a significant proportion of them develop metastases even after the primary tumor has been removed and they are given chemotherapy. We identified an inflammatory mechanism through which chemotherapy actually helps the development of metastases, and we even found a solution: adding an inflammation-inhibiting factor to the chemotherapy treatment. We hope that in the future our findings will reach the clinic and allow doctors to provide more effective treatment for breast cancer, and perhaps even for other types of cancer - treatment that will prevent the recurrence of the disease and save the lives of many patients all over the world," concludes Prof. Erez.

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- Unique RNA technology for personalized cancer medicine

- Researchers at Tel Aviv University revealed the mechanism responsible for introducing copper ions into the cell

- Cancer metastases sometimes form following successful chemotherapy treatment

- Lethal learning: a new interpretation of adaptive mechanisms of cancer cells

- Moving forward and staying put