Could robots replace the students in the laboratories? * He doesn't look like R2-D2 from "Star Wars," but British researchers said Wednesday that they have created an intelligent robot capable of conducting experiments and interpreting and reporting their results.

Mark Papello, Nature (translation: Dikla Oren)

Direct link to this page: https://www.hayadan.org.il/scirob.html

A scientist robot was introduced for the first time, which can formulate theories, conduct experiments and interpret the results - and all this at a lower cost than its human counterparts.

Regarding artificial intelligence, the scientist robot, designed by Ross King of the University of Wales in Aberystwyth, UK, and his colleagues, is not as smart as other computers such as those that play chess. However, combining the wisdom of a computer with the agility of a robot was no small matter.

"Although the technology for the various components of the robot already exists, putting them together and applying them to a real scientific problem is a significant engineering achievement," says Ron Chrisley, who develops artificial intelligence systems at the Center for Cognitive Science Research at the University of Sussex, UK.

The work is part of a long tradition of automation, says computer science expert Pat Langley of Stanford University in California. Already in 1990, Jen Zitko and his colleagues connected a computerized detection system to a robot, which performs experiments. They didn't publish their work at the time, but they deserve some credit, Langley says.

"There have been robot scientists for a while," Chrisley jokes. "But in the past we always called them students."

King programmed the robot to find which genes in yeast are responsible for making essential amino acids such as phenylalanine and tyrosine. To do this, the robot grew a strain of yeast in which several genes were missing and compared its growth to that of normal yeast in order to discover the role of the missing genes. Researchers have long since located the genes the robot was looking for, but King assures that they have not provided the robot with clues.

Attempts to gauge the efficiency of the robot in designing experiments showed that its performance did not fall significantly from that of a group of human scientists.

Mike Young, Chair of the Department of Life Sciences at the University of Wales, was one of the designers of the human trials. "The robot really beat me," he admits, "but only because I pressed the wrong key at a certain point in the test."

Like any good lab head, the robot is programmed to be considerate of the cost of the experiments it conducts. The test gave penalty points if the human scientists chose to conduct experiments, which cost more than the robot experiments. "Humans tend to choose more expensive trials if they believe the payoff will be worth it," says Young. This isn't necessarily a good or bad thing in the real world, he points out, but it helped the robot win.

Geneticist Steven Oliver from the University of Manchester, who helped select the robot's research project, says that the robot has the potential to do more than just performing drudgery. "The next step will be to make the robot discover something completely new," says Oliver, "maybe it can be used for drug discovery."

Chrisley's only concern is that a lab full of robotic scientists will reject failed experiments that might open a window to new areas of research. "Throughout the history of science, it has become clear to us that mistakes can lead to great discoveries," he says. "When humans do the dirty work in science, you always discover new things and unknown places."

Link to the original article in Nature

Yuval Dror version, Haaretz

Scientists and researchers dedicate decades of their lives to investigate and understand phenomena. They formulate hypotheses, conduct experiments, analyze the results and fit their hypotheses to the data they received. Although they are assisted by computers and robots, the help is usually limited to calculations or performing repetitive tasks. A group of researchers from Great Britain describes, in an article published yesterday in the journal "Nature", a system that consists of a laboratory robot and a personal computer - and that performs the entire scientific process that until now was under the exclusive control of humans: planning and conducting experiments, raising hypotheses, rejecting unreasonable hypotheses and drawing conclusions.

According to the British researchers, in recent decades there has been much progress in the field of artificial intelligence, especially in relation to the development of mathematical algorithms that allow computers to learn from experience. Despite this, they claim: "The impact of artificial intelligence on the scientific process was limited."

The scientific process, as it is described by the researchers, is carried out as follows: the researcher uses his experience and imagination to formulate a possible research hypothesis (hypothesis). In order to find out if the hypothesis is correct, he derives an experiment from it, and by means of it he tests it.

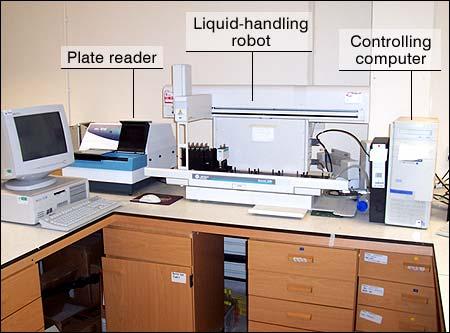

The researchers tested whether a computerized system could also perform this process without human help. They built a system consisting of a liquid handling machine controlled by a personal computer, a machine for testing the contents of flasks connected to another personal computer, and a third computer that collects the data, analyzes it and draws conclusions. The software that runs the system includes a basic background on the way scientific experiments should be performed, and a background in biology. From the moment the system starts working, almost no human intervention is required.

The scientists tasked the scientific robot with finding out the function of some genes found in yeast. They taught the robot how to mix liquids and how to pour them into the appropriate flasks and test tubes. From this moment on, the robot had to perform a series of experiments to reach the correct results. At each step the robot updated its hypotheses according to the results it received. The researchers emphasized that they did not help the robot decide which experiments it should perform and which conclusions it should draw.

They compared the degree of success of the robot to another series of experiments, carried out according to the strategy that instructs to carry out the cheapest experiments that have not yet been carried out (the "thrifty model"), and a third series of experiments carried out at random.

The test results show that the robot reached a level of accuracy of 79.5% in its answers, compared to 73.9% of the "thrifty model" and 57.4% of the random model. To reach an accuracy level of 70%, the scientist robot performed fewer experiments, at a cost that reached only one hundredth of the experiments performed in the random model. In relation to the "thrifty model", the robot performed half of the experiments, and their cost amounted to less than a third.

According to the researchers, the experiment performed by the scientist robot provides clear evidence that "part of the process of drawing scientific conclusions can be formulated and made automatic." According to them, a clear formulation of the process may save money, since currently, scientists carry out experiments regardless of their cost. In their concluding remarks, they write that there is great importance in automating part of the scientific process: "This will allow scientists to engage in the creative and significant leaps in the way, in which they excel."

For news at the BBC

The robotics expert

https://www.hayadan.org.il/BuildaGate4/general2/data_card.php?Cat=~~~736720043~~~65&SiteName=hayadan