Avi Blizovsky

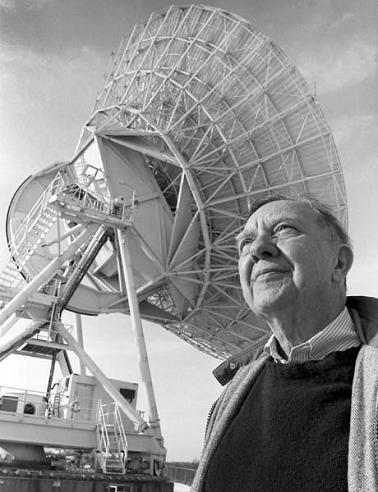

Physicist James Van Allen, a veteran space explorer who discovered the radiation belt that surrounds the Earth and bears his name, died last Wednesday, at the age of 91. The University of Iowa, where he lectured for years, announced his death on its website.

During his career, which spanned more than half a century, Van Allen designed scientific instruments for dozens of research flights, from small rockets to balloons, as well as spacecraft that flew to the distant planets and beyond.

Van Allen gained public attention in the late 1s, when instruments he designed and placed on board the American satellite Explorer XNUMX discovered a band of strong radiation surrounding the Earth, now known as the Van Allen Belt. The discovery opened a new field of research known as magnetospheric physics, in which more than a thousand researchers in twenty countries are currently working.

This discovery also propelled the US into the space race with the Soviet Union, prompting Time magazine to feature Van Allen on its cover on May 4, 1959.

Van Allen retired from full-time teaching in 1985, but continued to write, conduct experiments, advise students, and monitor the data coming from the satellites on which he designed the experiments. Although he supported a planned national space program, Van Allen was a harsh critic of most manned space projects and, among other things, claimed that the US proposal to establish a manned space station was speculative and poorly budgeted.

Explorer 1, which weighed only 14 kilograms, was launched on January 31, 1959, at a time when emotions were running high after the Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik 1, which sparked fears of an escalation of the Cold War. The devices Van Allen developed for the mission were simply tiny Geiger counters to measure radiation. Close to the 35th anniversary of the launch, Van Allen recalled in an interview with AP, how the scientists waited impatiently for confirmation that the satellite had entered orbit.

"When the signals finally came, there was great joy." The success of the flight led to celebration on a national scale, similar excitement was due to the scientific discovery of the radiation belt, a discovery that continued gradually over the following weeks and months as scientists continued to collect the data coming from the satellite.

"We discovered a completely new phenomenon that was not known or predicted in advance," Van Allen said. "We were on top of the world." That same year, another scientist suggested naming the belt after Van Allen. Later, instruments designed by Van Allen were uploaded to the Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft, which studied Jupiter's radiation belts in 1974-1974 and Saturn's radiation belt in 1979.

Van Allen continued to monitor the data from Pioneer 10 for decades, as this spacecraft became essentially man-made taking place in the most distant place, billions of kilometers from Earth.

Closer to Earth, satellites revolutionized communications, military intelligence, and environmental monitoring. When asked in 1993 if he predicted the revolution in communication satellites he said: "I guess the honest answer would be that I didn't, but I wasn't surprised either. These things were already in the corner."

In 1987, President Reagan awarded Van Allen the National Medal of Science, the highest honor for scientific achievement in the United States.

Two years later, Van Allen won the Crawford Prize, which has been awarded by the Swedish Academy of Sciences since 1982 for scientific achievements in fields where Nobel Prizes are not awarded.

Throughout his career, he continued to promote the unmanned satellites, saying that the manned flights gobbled up funds but the unmanned flights delivered the goods and met the scientific expectations of them and also continued to greater distances than the manned flights."

In his testimony before a congressional committee in 1985, Van Allen said that President Reagan's $20 billion plan to build a space station was speculative and poorly funded, and therefore pointless. And he was indeed right.

In 2004 he spoke again, this time against the plan of the current president, Bush, to establish a manned station on the moon and a manned mission to Mars. "I am one of the most dedicated supporters of the space program, but my position is that it can be done by robots much cheaper and with a higher quality of results," he said.

Van Allen was invited to become a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1959. He also served as a consultant to the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment (a position that has since been canceled), as well as being a board member at NASA and a member of the Space Sciences Council at the National Academy of Sciences.

Drafting and editing: H. J. Glykasm, translations and technical writing