A new study at the Hebrew University examines why the farmers of the past preferred the mountains of Jerusalem over the mountains of the north?

In the Jerusalem mountains, the Judean plains and the Samaria area, it is evident that the area has been shaped for thousands of years by humans, usually by building terraces. In these areas there are many archaeological finds, among them textile houses, ghettos, guardhouses and other agricultural facilities, all of which testify to the existence of a prosperous agricultural society for thousands of years. But in the Galilee Mountains, where it is evident that there is great wealth in sediments, but little evidence of extensive agriculture. Did and why did the farmers of the ancient past prefer the land of the Jerusalem mountains over the north? What was so unique about her? They tried on this answer Prof. Yehuda Anzel from the Institute of Earth Sciences at the Hebrew University and Dr. Rivka Amit and Dr. On Cherubi from the Geological Institute to answer in a new study, recently published in the journal Geology. The assumption of the researchers was that the proximity to the loess soil in the southern region of the country was the secret of the local ancient farmers.

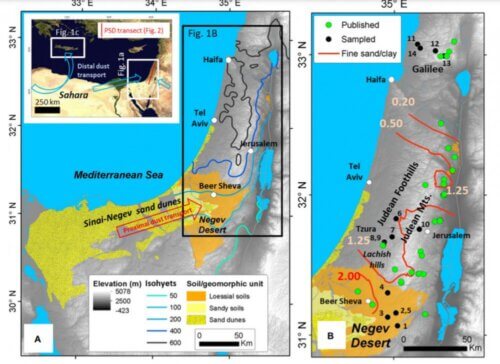

Chart from the study:

At the beginning of their work, the researchers tried to trace the origin of the loess in the Negev, and to understand what the landscape in our region looked like in the ancient past. Loess is a soil made up of very small grains: smaller than sand, but coarser than dust. These grains are called coarse silt. The source of this silt, also called loess, is the sand dune field of the Negev and Sinai. In our region, Hellas covers most of the southern part of the country. The coarse silt or loess is limited in its transport distance by the wind to tens of kilometers in contrast to the fine dust that moves in the atmosphere thousands of kilometers. Its origin, therefore, cannot be in the Sahara or the Arabian deserts, since the winds cannot drive its relatively large grains over such long distances. That is, the main contribution of the coarse silt is to the areas close to the source, i.e. the Judean Mountains, the Hebron Mountains and the southern lowlands, which are characterized by thicker and more productive soil than in the northern Levant. Previous studies show that the age of the loess supply episode in this area is relatively young, about 200,000 years younger. If so, the question arises as to what kind of soil characterized the southern Levant before the period when the loess entered our area.

The researchers moved on to investigate the composition of the soils on the tops of the mountains in Israel, areas where there is no fear of loess particles mixing with materials or possible transport by streams. They separated the loess into its components and found that the size of the grains was between 20 and 60 microns, most of it was quartz, meaning that it did not originate from the limestone rocks on which it is found (most of the rock in Israel is calcareous). It has been shown that the hels came from a nearby source, with the only nearby place capable of providing quartz being the dunes. It is estimated, therefore, that loess in Israel was created by the weathering of the sand dunes of the Negev and Sinai under different climate conditions than those familiar to us today, when the strong winds that operated in the region during the Upper Pleistocene caused the grains to crush each other and turn from sand into loess.

The conclusion of the study is that a massive supply of loess to the mountainous areas in the southern Levant changed the nature of the soils in the areas close to the loess area, enriching the ecology of the Levant and thus probably influenced the development of the early civilization of this area. The high amount of coarse silt grains in the southern Levant region contributed to a uniquely sustainable agriculture in this region, and helped turn the Levant into a "land of milk and honey".

The researchers concluded that there are two sources of soils in the Land of Israel: the first is dust carried from afar, over thousands of kilometers, from the Sahara or the Arabian deserts. This dust is fine grained, and can create relatively thin soils. The second is coarser loess grains, which can only come from a nearby source, only a few tens of kilometers. The southern soils benefit from these two sources - and the coarser grains also created a relatively thick and aerated soil, rich in nutrients and one that better preserves the water that is absorbed into it. As you go up north and away from the local desert, the coarse grains decrease and the soils, in the mountainous areas, become thinner. "Without the desert loess, it is likely that we would not be a land flowing with milk and honey", Dr. Amit explained in an interview with Haaretz newspaper, And Prof. Anzel adds that "this study supports the conclusion of Herodotus who already in the 5th century AD came to the understanding that the silt and not the clay is necessary for the existence and development of the Egyptian culture close to us."

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- Israeli researchers discovered evidence of the collapse of a commercial vine branch in the Negev 1500 years ago, during a time of plague and climate change

- Economy 16 Chapter XNUMX: Under the Romans after the destruction of the Second Temple: Small or large farmThe economic situation in the country

- country economy Israel from the second century AD onwards - Chapter Two - Agriculture: Capital and Government