The tentacles, relatives of the mosquitoes, have a strange wedding custom, they choose their spouse in a huge swarm of tentacles and yet continue to stick together. A new study managed to decipher the phenomenon

In a swarm of mosquitos - the kinder relatives of mosquitoes (mainly because they don't bite) - sometimes something surprising happens: two members of the swarm cling to each other, cross the swarm from side to side and at the same time swirl around each other like a pair of dancers. Scientists wondered the meaning of the strange "pairing": are these two adversaries struggling, new allies - or perhaps the male of the "toucher" will touch another to check if it is, by chance, a hex that accidentally fell into a swarm that usually consists of only males? Weizmann Institute of Science scientists and their research partners They discovered that the strange pairing is probably not related to the social preferences of the touchers.

How could pairs of hexagons be possible in a chaotic swarm composed of insects flying at the highest speed? These pairs were recorded at Stanford University as part of an experimental swarm of the strain Chironomus riparius. In this experiment, the scientists clearly showed that some pairs of tentacles crossed the swarm from side to side up to eight times in a row.

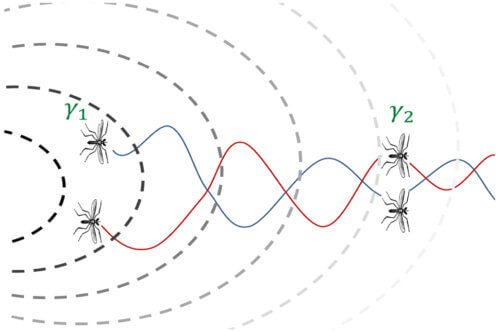

Prof. Nir Gov and the post-doctoral researcher Dr. Dan Gorbonos from the Department of Chemical and Biological Physics, previously developed a physical model that explains how insect swarms are formed. According to this model, insects "know" how to attract each other with the help of the buzz they make in flight. Within the framework of the model, and as sometimes happens in biological sensing systems, the insects' sensitivity to buzzing changes dynamically depending on the circumstances: they are less sensitive to noise when they are in the center of the swarm, but at its edges, where the buzzing is weaker, their sensitivity increases.

In the new study, Prof. Gov and Dr. Gorbonos used a model to explain the formation of pairs within the swarm. They analyzed the flight paths of the tentacles as recorded by the researchers' cameras at Stanford and concluded that the formation of pairs could be explained by the insects' attraction to the hum and their varying sensitivity to its intensity. In other words, when the tentacles hover in the center of the swarm, the noise around them is high, and as a result their sensitivity to noise is low, so they are not attentive to the hum of other tentacles. However, when two hexapods find themselves flying side by side while moving away from the center of the swarm, their sensitivity to the sound of the hum gradually increases, and at a certain moment the hum they perceive from each other becomes louder than the background noise of the swarm - and this causes them to fly "in pairs" until this delicate balance is violated . Relying on these principles alone, the scientists were able to predict the paths of the pairs of tentacles recorded in the Stanford experiment, without using hypotheses about potential biological motives for the insects' behavior.

These findings not only provide an explanation for a mysterious phenomenon in insects - they may also explain group behavior in other biological systems, for example flocks of birds, bacterial colonies or clusters of cells. In addition, the findings may also be used in human-made systems, for example, in predicting possible interactions within groups of robots or drones.

Dr. Kasper von der Vaart, Dr. Michael Sinhover and Prof. Nicholas T. Ouellette from Stanford University and Prof. James G. Puckett from Gettysburg College in the United States participated in the study.

More on the subject on the science website: