David Rap, Haaretz, voila!

18th century Chinese silk creation. A cat will continue to hunt even when it has no survival need to do so

When you look at the fossilized remains of Smilodon populator, modern day tigers, its very distant relatives, seem like shy cats. The fangs of the predator, whose dimensions were like those of a lion, reached a length of about 30 centimeters, and protruded from its mouth, which it could open up to 90 degrees. It seems that his method of killing his prey was to hit the victims stomach or neck arteries, waiting for them to bleed to death.

The Smilodon, which became extinct about 11 years ago, is a descendant of the saber-tooth family. This family is a split, which has not survived to this day, from the cat family, which includes, among others, tigers, lions, wild cats and domestic cats. All of these had common parents, who, according to fossil research, lived on Earth as early as 60 million years ago.

The cats as we know them today evolved in the last 15-10 million years. The internal division within this family has caused much controversy among scientists. Today it is common to define four to eight separate genera in this family, including about 36 species. Animals from the cat family have evolved in most regions of the world, but until the arrival of domesticated cats, they were absent from Australia, Madagascar and many other islands.

Whether these are tigers, which may reach a weight of 250 kilograms, or the apex, whose weight is around three kilograms, most members of the cat family (some of which also divide into big cats and small cats) have similar characteristics. All cats are carnivores, meat eaters adapted to catching animals and killing them. They are agile, moving on their toes and pulling out their claws only when necessary, giving them a very typical gait. Their jaw muscles are strong and enable a powerful bite.

Most cats are good at climbing, and have a relatively long tail for their body, which helps with stabilization and sharp turns in the (usually short) pursuit of prey. Their sense of sight is highly developed, and in some of them it is also adapted to night vision. As territorial creatures, most of them live alone, except during the estrus periods.

The following species from the cat family live in Israel: the wild cat, the swamp cat, the sand cat, the caracal (desert cat) and three subspecies of tigers. In the distant past, lions also lived in the area. Another species, the cheetah, was last seen in Israel in the 37s. Of the dozens of cat species, about a third are in danger of extinction. The most prosperous species among cats, in the world and in Israel, is of course the domestic cat, but researchers disagree on whether it can indeed be defined as a separate species, the XNUMXth in the family.

Expert hunter in the backyard

Five cats joined the meteorological expedition that sailed in 1949 to Marion Island, east of Australia. 26 years later, the offspring of these five cats were the reason for new research expeditions: the cat population on the island grew and reached in 1975 about 2,140 individuals. Each year, these eliminated about 450 thousand shrike, waterfowl that nested on the island for hundreds of years, without having to deal with predators from the cat family.

The damage caused by domestic cats to animal populations around the world is enormous. The damage is most severe in areas where there were no predators before the arrival of the cats. The damage is not only related to cats that have become feral, but also to domestic cats.

A paper written about a year ago by Inbal Brickner from the Department of Zoology at Tel Aviv University, under the direction of Prof. Yoram Yom-Tov, discusses the predation of animals by cats. In the United States, it is estimated that domestic cats prey on about a billion mammals and hundreds of millions of birds each year.

Brickner insists on the relative advantages of cats compared to other "natural" carnivores: the domestic cat is vaccinated and treated, and because of this its health status is improved; Its food is regularly supplied, and its population size is not affected by changes in the size of the prey population; The cat population is hardly regulated by territorial behavior; The cat is active during the day but also at night, thereby increasing its effectiveness as a predator.

The cats also push out other predators, which are less adapted than them for hunting; transmit diseases that can seriously harm wild animals; The mating of domestic cats with wild cats harms the "pure" wild cat population and threatens extinction. In Australia it is estimated that cats exterminated about 40% of small mammal species already in the middle of the 19th century. In New Zealand, since the arrival of Western man, about 40% of land birds have been exterminated, about a quarter of them directly by cats.

In the Galapagos Islands, the marine iguana, endemic to the place, is in danger of extinction in all those islands where cats have been brought. In a case documented elsewhere, about 15 thousand iguanas became extinct in less than two years, after the establishment of a hotel on an isolated island, not due to the arrival of visitors, but because cats were brought there.

Cat owners may not like to hear this, but when they allow their cats to go for a walk outside the house they are releasing an expert hunter. In Canada, where researchers estimate that about five million cats kill about 140 million birds and small mammals every year, in recent years there has been a call for cat owners not to let their cats out of their homes. Studies from recent years show that the domestic cat's hunting instinct is not completely suppressed by food supply. In other words, a cat will continue to hunt even when there is no survival need to do so.

In Israel, which has almost no areas that are truly remote from human settlements, the problem is extremely difficult. It is estimated that animals such as the green lizard in Carmel and the Hamaria bird have been greatly affected by the ever-increasing population of cats. Studies have shown that the cats that roam a military base on Mount Maron hunt an alarming number of reptiles and small mammals every day. The damage caused by cats in nature reserves in the Judean Desert, for example, is considerable, and has even increased in recent years, after a public struggle that led the authorities to eliminate fewer and fewer cats roaming the area, claiming that this is cruel.

In her work, Brickner presents the complexity of the dilemma, as it is manifested in England. Every year tens of thousands of foxes and birds are shot across the country in the "sport" of hunting. Animal lovers have launched an aggressive campaign on this issue, but at the same time, some of them release into the yard every day many more skilled hunters - domestic cats.

Man's most popular friend

It was a velvet revolution: a quiet and non-violent global change, which began several decades ago, under the noses of dog owners. Its most distinct signs could be seen in the United States seven years ago. In 1997, the veterinary services in Washington estimated, mainly based on information regarding the amount of pet food bought throughout the country that year, that there are more than 70 million domestic cats in the US, compared to about 55 million dogs.

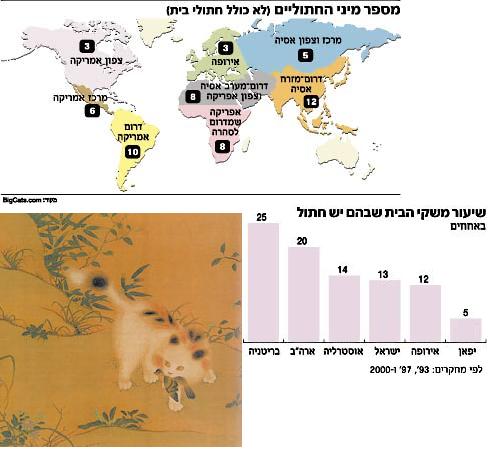

The new world lagged behind the old world in this matter: in England, surveys showed as early as 1993 that in about 25% of homes across the country, the residents keep "at least one cat". The cat took the place of the dog as the favorite pet.

In 2000, researchers estimated that the ratio between cats and humans in the US is 20%, that is, for every five humans - one cat. In Europe the ratio was more than 12%, in Australia about 14%, and in Japan about 5%. However, these data only referred to domestic cats, those who depend exclusively on their owners' dry and wet food bags and others who go looking for supplements outside the home.

Estimating the size of the population of stray cats and feral cats - those that have returned, even if reluctantly, to nature - is a much more difficult task. According to estimates, there are between 10 and 70 million such cats in the US.

In Israel, researchers estimated, based on surveys conducted in 1987, that the domestic cat population is around 65-50 cats. Another survey was held ten years later, by Prof. Yosef Terkel and Shani Doron from the Department of Zoology at Tel Aviv University. This survey showed that about 13% of parental homes in Israel raise a cat. The number of cats was thus estimated at 190-160 thousand. It was found that about 12% of Jews breed cats compared to about 17.5% of Arabs.

Among the Jews who participated in the survey, no ultra-Orthodox cat breeders were found. In contrast, 8.2% of the religious responded that they raise a cat, as did 10.8% of the traditional and 17.4% of the secular. About 19% of the respondents reported that they keep another pet - usually a dog - a figure that indicates that in Israel the population of domestic cats is still smaller than the population of dogs.

The survey examined many characteristics of the public's attitude towards cats: the 35-24 age group was less inclined to breed cats compared to other age groups, and the survey editors speculate that this is due to the fear of young couples about a cat harming young children.

The survey also revealed that the single population expressed the highest values of "love" towards cats. Women were more likely than men to be afraid of cats. The Arab respondents expressed higher values of love - but also of fear - towards cats, compared to the Jewish respondents.

A relatively new guest in the human habitation

By David Ref

Egyptian wall painting from the 13th century BC. Active or passive domestication

Goats, sheep, horses and pigs were domesticated by man long before the process of domestication of the wild cat began. Even compared to dogs, domesticated about 12 thousand years ago, cats are new guests in human habitations.

In Cyprus, the remains of a cat were recently found in a burial site dating back to the tenth millennium BC. There is no proof that it was a domesticated cat. Cat bones were found among the remains of ancient human settlements, for example in the Jericho area, in excavations whose findings date back to the seventh millennium BC. One explanation is that these were wild cats, which were captured and killed so that humans could use their fur.

Egypt is the cradle of the development of the domesticated cat. Remains of cats were found in areas of human habitation, in sites dating back to the third millennium BC. Feral cats were attracted to food in the human environment. The cats provided excellent protection against the culture from rodents - rats and mice - that damaged the grain. The farmers encouraged your stay near their houses and fields. According to one of the theories, this is how the process of their domestication began, in a rather passive manner, about four thousand years ago.

According to another theory, the farmers sped up the process: in their quest to ensure a permanent community of rodent predators, they began raising wildcat kittens. The common species in North Africa is called Felis Silvestris Lybica, and is a wild cat with a relatively easygoing temperament. Naturally, those puppies that had less wild traits than their brothers survived in the houses, and this is how a species with a high adaptability to life among humans developed.

It is likely that both theories are correct. In works of art from Egypt, from the second millennium BC, depictions of cats in the company of people begin to appear. The closeness between man and animal indicates that these are not wild wild cats. Thus the researchers could rely on visual information when coming to date the domestication.

In Egypt, cats were seen as sacred animals, which should not be taken out of the realm of the kingdom. With the weakening of pagan beliefs, at the same time as the rise of Christianity, these prohibitions were removed and the cat began to spread to the region and most parts of the world. In each meeting of domesticated cats with local populations of wild cats, for example in Europe, new subspecies of cats were created.

A long, low howl - a sign to fill the plate

By David Ref

Researcher Nicastro and two of the research participants. Cry manipulation

Interpersonal communication is a skill that can be developed. This is true for humans, and it turns out that from a historical point of view it is also true regarding cats, or more precisely - in relation to communication between them and humans. It seems that over the last thousands of years, when cats lived alongside humans, they adapted ways to approach their owners and get what they wanted.

At Cornell University in the state of New York, a study designed to test the ability of cats to communicate with humans was completed about two years ago. The research was conducted by Nicholas Nicastro, a psychology student, under the direction of Prof. Michael Everen, and cats and students participated in it. Nicastro first addressed a group of 12 cats including his two cats. He recorded a hundred voice samples of them in different situations: while they were waiting for food that was lingering; when meeting with their husbands; When they are irritated (for example when their fur is brushed for a longer time than usual) and also without special stimuli.

In the next step, he played the hundred sounds to 26 students, who were asked to indicate in values ranging from 1 to 7 how pleasant each howl was to their ears. 28 other subjects were asked to rate the same hundred recordings according to the sense of urgency and demand they evoked in them, also in values ranging from 1 to 7. Analyzing the results, it became clear to Nicastro that there is a clear negative relationship between the definition of a howl as "demanding" and its definition by others as "pleasant". He was not satisfied with this expected conclusion, but tried to characterize the vocal nature of the various wails.

Nicastro discovered that the human subjects attributed a demanding and urgent meaning to long, low sounds. Short howls - especially those that appeared at a high frequency and then at a low frequency - were perceived by the listeners as much more pleasant and less demanding.

In the next phase of his research, Nicastro made a comparison between the sounds he recorded in the 12 domestic cats that participated in his research and the descendants of their ancestors - the wild cats. He visited the zoo in Pretoria in South Africa and recorded the sounds of wild cats there. In the comparison he made, he determined that the voices of the wild cats were much less pleasant to the human ear.

Based on his findings, Nicastro claims that in the not-so-natural selection process of domestic cats, since they began domesticating them, those cats survived whose voices sounded less aggressive and more pleasant to their owners. The explanation he puts forward is that domestic cats have developed a fairly good ability to "manipulate howling", which they exercise on humans who satisfy their various needs.

Thus, for example, a cat accustomed to receiving its dinner at seven o'clock in the evening may enter the feeding room and make a sound expressing dissatisfaction and irritation if the designated hour has passed and its plate is still empty. Its owner, Nicastro claims, will understand the meaning of this special tone of voice and know how to distinguish it from another howl, which means satisfaction or pleasure.

The penalty for killing a cat: death

By David Ref

A cat made of wood from Egypt, 7th-6th century BC, from the collection of the Hecht Museum, Haifa University. Cats were buried along with milk vessels and mice

Street cat feeders are a common sight in any big city these days. The Greek historian Herodotus, who lived in the fifth century BC, was probably not mentally prepared for this phenomenon. In 450 BC he arrived at the city of Bobstis in Egypt, east of the Nile Delta. When he visited the temple of Bastet - the goddess of joy and love, whose sacred animal is the cat - he was amazed to see thousands of cats walking around and crowds of priests milling around them, taking care of their needs and feeding them.

Before the first millennium BC, there was some confusion among the goddess's worshipers about her exact feline nature and about the identity of her relatives. In Egyptian myth the male cat was one of the animals sacred to the sun god, Ra. The goddess Sekhmet, the consort of the creator god Petah, and who fought the enemies of Ra, was described as having the head of a lioness. In some versions of the Egyptian myth Bastet was presented as Sekhmet's sister, and as befits a relative she also appeared with the head of a lioness.

As the years passed, the estate became like her home, and her face gradually changed. Is it a coincidence that its face was described as a cat's face, at the same time as this animal's horn rose among the farmers along the banks of the Nile? Be that as it may, Bastet has become the goddess-cat. Every year thousands of pilgrims came to the town, Bobstis. It was worth being a cat in those days in Egypt. For the animal, which was considered sacred to the gods, special food was prepared and there was a strict prohibition against harming it. The penalty for killing a cat was death. In the testimonies of visitors to Egypt from the first centuries BC, it is said that at the sight of a sick or injured cat, people used to flee the place, for fear of being mistakenly accused of harming it.

Those whose cat died practiced mourning rituals: the family members shaved their eyebrows, as a sign of respect for the dead, while the cat was buried in a cemetery for its own kind, and sometimes underwent a full embalming process. There were cats that were buried with vessels for milk, or even mice, to help them pass their years in the next world.

At the end of the 19th century, an Egyptian farmer uncovered a huge burial cave in the Bnei-Hassan area, on the banks of the Nile. This was not a grave plot intended for people, but for cats. Remains of tens of thousands of cats, most of them mummified, were found there. The chain of events symbolized the decline of the cats in the eyes of man: an Egyptian businessman hired laborers, and loaded the thousands of ancient corpses of the cats on a ship sent to Britain. The bodies were used to fertilize agricultural land.

A small part of the embalmed were preserved and years later were dated to the period between 2000 and 1000 BC. Some tiger skeletons were identified among them, but most of the cats were of the local wild cat species common in Africa - the father of the domestic cat.

Another large group of feline skeletons was brought to the British Museum in London at the beginning of the 20th century. The findings were dated to 600 to 200 BC. Next to the skeletons of tigers and dogs there were mainly the local wild cats, which the Egyptians adored for thousands of years. They admired them so much that they banned their trade and their export outside the kingdom. However, the inspectors, who were sent in some cases to the neighboring countries, to locate cats that were exported in violation of the law, were unable to prevent some of them from finding their way to the outskirts of the empire, for example to Israel and gradually also to the Greco-Roman world.

Like SARS, only much deadlier

By David Ref

cheetah. was hit much harder than the cat and the man

The first patient was apparently infected in a hospital. A short time later the epidemic broke out. It was caused by a corona type virus, which until then was known in the medical literature as a virus that causes only mild symptoms in most patients.

This is not a description of the SARS disease, which broke out in November 2002, but a description of the beginning of an epidemic, which in the early eighties spread among the cheetahs (cheetahs) in a wildlife park near the city of Winston in the state of Oregon in the United States. An article discussing the implications of this epidemic was recently published in the electronic edition of the journal "Current Biology".

The article, written by researchers at the National Cancer Institute in Maryland, presents the details of the case. Before being transferred to the park in Winston, the cheetahs were examined at a veterinary center in California. The researchers estimate that at the medical center, where many cats are treated, one of the cheetahs was infected with the corona virus, which usually affects cats and causes peritonitis (FIP). The cheetah probably carried the virus with her to her new home in Oregon.

The results of the appearance of the virus in the cheetahs in the park in Oregon were terrible: a few months later it was found that 100% of them carried the virus. 90-60% of the cheetahs in the park developed severe symptoms such as diarrhea, weight loss, jaundice, gingivitis and kidney problems. 60% of the sick cheetahs died within three years of infection.

Why did the virus cause such high mortality among the cheetahs? The study claims that the assumption that the virus underwent a rapid mutation, which made it especially violent, is not reasonable. This is because the lions in Winston Park, some of whom were also infected with the virus, did not develop the disease at all. It seems that the reason for the great vulnerability of the cheetah population lies in the very little variation in their genetic load. The cheetahs, which almost became extinct about ten thousand years ago, have since evolved from a small number of individuals. It so happened that the genetic variation within the group of cheetahs, which currently live in the wild only in Africa and Iran, is very low. A virus that overcame the immune system of one of the cheetahs, is likely to be able to overcome the immune system of her relatives.

The SARS disease, which is caused by a (different) corona virus, broke out in Adam in March 2003. It first appeared in China but soon spread to dozens of other countries. In less than a year, more than 8,000 people contracted SARS, and close to 10% of them died.

A comparison of the three corona viruses - in a cat, a cheetah and a human - reveals interesting details. In all three species the virus was highly contagious. But while in humans and cats the mortality from the diseases caused by the virus ranges from 5% to 10%, in the case of the cheetahs in the North American park, about 60% of the individuals infected with the disease died from it.

On the other hand, when you look at the ages of the individuals affected by the disease in the most severe form, there is a distinct contrast between the feline family and humans: the Sars disease mainly affects older or sick people, and among them the mortality from it reaches about 50%. In cats and cheetahs, most of the victims are young individuals (in Winston Park, 85% of the cheetah cubs died in the epidemic).

https://www.hayadan.org.il/BuildaGate4/general2/data_card.php?Cat=~~~898326176~~~195&SiteName=hayadan