Was it true that Herzl's "Jewish State" was born from the "great spirit" of Herbert Spencer, a thinker whose name is mainly associated with the view known as "Social Darwinism" and "Natural Selection"?

Yaakov Shavit, Haaretz, News and Walla!

Don't we know what stages of development the human race has gone through since the beginning... the road always leads to heaven

Direct link to this page: https://www.hayadan.org.il/herzl100y.html

On March 21, 1897, Benjamin Ze'ev Herzl sent a copy of the English translation of the booklet "The State of the Jews" to the elderly English philosopher Herbert Spencer along with a letter, only the signature paragraph of which is quoted in the diary from that day: "We are both guests on this earth at the same time. According to the way of nature, it is possible that you will leave here before me, who is 37 years old (Herzl passed away a year after Spencer, who died in 1903, aged 83). That's why I want to know and be proven - for I am already convinced that the Jewish state will arise and be in one form or another, and it is possible that it will be beyond the limit of my lifetime - how the beginning of this enterprise was reflected in the great spirit of Herbert Spencer."

We will not know what Herzl wrote in the letter; Its full text was not printed in the various editions of Herzl's letters, and the search in Spencer's estate turned up nothing. All that is known is that Spencer's secretary answered Herzl politely, that due to his poor health the philosopher would not be able to answer, even though the question of the Jews interests him. Anyway, to the letter

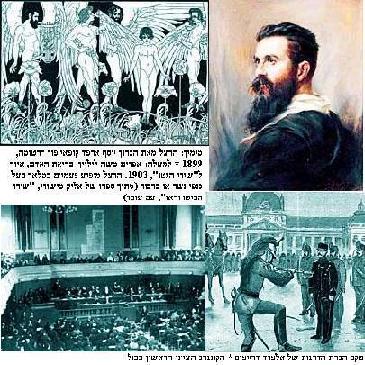

Herzl by Baron Yosef Arpad Kupai von Dartoma, 1899

This was not given importance, and it was seen at most as evidence of Herzl's desire to win polite words of encouragement. However, Herzl did not send the pamphlet "to the best philosophers of his time" (as claimed by Jacob Golomb in his article on Nietzsche's influence on Herzl), but only to the Danish Jewish writer critic Georg Brands, who reacted disdainfully to it, and to Herbert Spencer, the author of "Synthetic Philosophy".

Apparently, one can understand the choice of Spencer: Nietzsche defined him as a respectable, but mediocre Englishman, but Spencer's influence on the European intellectual world in the last third of the 19th century was no less than that of Nietzsche. As a literary proof of this, we will cite Anton Chekhov's novel, "Duel". When the hero of the novel, Ivan Andreyevich, tells Ayavsky about his love affair, he says: "How much civilization has spoiled us! I loved a woman-man; She is also loving me... first we had kisses, and silent evenings, and swearing, and Spencer too...". When the young zoologist, Von Kuran, comes out against Lajavsky's pessimistic mindset, he claims that he treats Spencer like a "brat": "He pats him on the back like a paternal pat: "What's up, Brother Spencer? He, of course, did not read Spenser (…) that fool has no right not only to speak of Spenser so pleasantly, but even to kiss the sole of Spenser's shoe! To subvert civilization, under the rabbi, under a foreign altar, to splash mud (...) Only a vile and despicable beast, extremely selfish, is capable of this" (translated by M.Z. Valpovsky).

Herzl's words that the "Jewish state" was born from the "great spirit" of a thinker, whose name is mainly associated with the view known as "social Darwinism" are puzzling; In the teachings of the one who coined the principle of "natural selection" as a mechanism that generates progress. If Herzl did indeed mean more than words of flattery, does this not tarnish the originator of political Zionism and his utopian vision? It seems not. In the eyes of Herzl, as in the eyes of the radical intelligentsia, Jewish and non-Jewish, in Central and Eastern Europe, Spencer was a thinker of the idea of the inevitable development and improvement of society. His biological-scientific positivism was an important weapon in the fight against religious rule and autocracy, which seemed responsible for the backwardness of societies in this part of Europe.

As evidence of Spencer's influence on Jewish thought and publicism, I will limit myself here to four witnesses: in a list on the occasion of Spencer's 82nd birthday, Nahum Sokolov described him as a teacher of the way for all those who want the "informed development, deepening and perfection of the human and Hebrew spirit (which is one) in the Jews. If we wish to encourage the nation through revival, development and completion - we are standing on the foundation of the law of development." Max Nordau saw Spencer as an important opponent of Nietzsche's fashionable "nihilistic pessimism", and in his thought he saw an antithesis to theology and metaphysics. In a sharp criticism of Ahad Ha'am, YH Brenner wondered: "Is it a method to champion the name of Spencer and his method of development and at the same time talk about the eternity of Judaism and morality, which will not be changed or replaced?" Dr. Yehoshua Tahan wrote in his book about Spenser (Odyssa, XNUMX), that the English philosopher taught that in the ideal situation "a person does good without compulsion or necessity, but only if it is pleasant (and useful) to do it", and that morality means "the alignment of actions to a purpose".

Well, Herzl's appeal to Spencer should come as no surprise. Despite his criticism of the European political culture of the second half of the 19th century, Herzl was not infected by the pessimistic trend of the Fin de Siecle and did not foresee the incurable degeneration of European civilization. Because Herzl believed in the inevitable process of progress and in the "Age of Inventions", as he called the 19th century "Goles". Herzl was full of admiration for the achievements of science and technology, although in several articles, stories and platoons from his pen he questions the connection between technological and scientific progress and moral behavior in the international and social arena. In Philoton "The Guided Airship" (from the end of May 1896, about which he wrote that "it was generally understood as an allegory for the Jewish state"), Herzl described the great transformations that would be wrought in the world by "toys" such as horseless carriages and the "airship", which could become a warship" and a future device to spread pleasures to those in power and "new forms of poverty and destitution". Apparently, Herzl thereby anticipated the prediction of "G Wells" in the futuristic novel "When the Old One Wakes Up" (1899) regarding the destructive use of aerosols. However, the speaker "the Pharisee" in this story sums up the exchange in a completely different spirit: Joseph Miller, who invented the "guided airship", needs to think about the future, since "everyone who prepares the future must look from the present and beyond. Let the good people come."

In another story, "The Automobile", from 1899, Herzl describes the effect the car will have: "Every car owner has a small house surrounded by a garden in the distance. Life on the main roads is more pleasant (...) The new way of life cultivates a new type of people, in which the culture of the peasants and the strength of the townspeople joined together." Although he added a caveat: "How fast is our travel (...) how slow is our wisdom", but close to that, on June 21, 1899, after visiting an automobile exhibition held in the Tuileries Gardens and admiring the "new American Cleveland car", he wrote in his diary: "The cars were created for us. We will have cement roads, fewer rails, and in advance we will install new forms of transportation." If H.G. Wells believed that humans created the future without thinking about its results, Herzl believed that man with his intelligence is able to predict the results that technological inventions will have and prepare himself for them. In the introduction to "The State of the Jews" he wrote "Machines are mighty slaves of spirit at the service of man". No wonder there were those who called Herzl not only a utopian, or a false messiah, but also "the Jewish Jules Verne".

It seems therefore that Herzl did not believe that science and technology were the cocoon that could arise over its creator. In his writings, neither the "private" nor the "public", there is no echo of the opinion prevalent in the writings of Jewish publicists at the end of the 19th century, that there is no necessary connection between civilizational progress and moral behavior. Material progress, wrote the radical intellectual Yehuda Leib Levin, did not strengthen social morality, but rather gave power to the immoral who operate according to the principles of social Darwinism. As a visionary, Herzl cannot doubt the power of science and technology to create a new reality. In order to create a mass movement and organize modern immigration and settlement, tools are needed - "all the stock of the year 1900", all the achievements and assets of the 19th century.

In a "speech" before the council of the Rothschild family from June 1895 (see, among other things, in the additional news) Herzl wrote: "The new migration of the Jews must be done "according to scientific principles", and must use "all modern means... You, gentlemen, It is good to know what things can be done with money. How fast and without risk we now race in huge steamships over days we never knew before. We pull safe railroads up mountains previously climbed on foot with trepidation. A hundred thousand minds are constantly trying to think how to take from nature its secrets..." (translated by Yosef Vankert). My socialism, he wrote in his diary on June 8, 1895, "is a pure technological matter. An equal distribution of the forces of nature through electricity." And in a speech in the East End on July 13, 1896, he stated in the same spirit that Jewish immigration has an advantage that will make it a unique immigration in history: it will have the opportunity to adapt all modern settlement methods. This opinion is repeated many times in his writings: it is the statement that opens the booklet "The State of the Jews", and it is a central motif in the utopian novel "Altneuland". Science and technology will make it possible to create both the framework and the economic and social mechanisms that will prepare a new Jewish society and the creation of a new Jewish person.

There was therefore no flattery in Herzl's words that Spencer's "great spirit" hovers over the "Jewish state". "We do not know what stages of development the human race went through from the days of its beginning until it reached civilization. The road always leads to El Al"

Such a sentence as the loyal customer from Spencer. Herzl believed that human society is driven by an internal mechanism of perfection, which leads society from homogeneity to heterogeneity. At the peak of the process appears the liberal commercial-industrial-scientific society; A society without coercion, which eradicates the tendency to aggression and war, overcomes religious and metaphysical thought, and is the condition for a liberal-democratic regime, freedom, voluntary cooperation, equal opportunities, love of others and happiness.

In the section of the diary mentioned from June 1899, Herzl wrote that under the influence of the automobile exhibition in Tuileries it occurred to him to develop the idea of mutualism: "Between capitalism and collectivism, it seems to me that mutualism is the golden path." Some have found the source of this "reciprocity" idea in the writings of the French utopian Joseph Proudhon (1865-1809), and therefore it is unthinkable that the idea was borrowed from the owner of the "Darwinist" principle of "the survival of the fittest". However, Spencer was not opposed to the principle of mutual help, and in his book "Essods Torat Hamidot" he proposed "scientific ethics" based on the distinction between "absolute ethics" and "relative ethics", and supported mutual aid that should be based on a free will contract for the division of labor. Herzl could therefore write to Spencer that the society of the future he conceived would behave according to the patterns of this "ideal behavior". He could also write that, like Spencer, he also seeks to define in advance the conditions necessary for a perfect life, because they are conditioned by the economic and social conditions.

The intention is not to adopt technological progress only for the purpose of realizing pragmatic Zionist needs. Progress is a situation that must be worked upon for its fulfillment because it alone offers the conditions for the establishment of a "moral" society, or, more correctly, a "just" society. When Herzl writes about the need for "power", he means the need for the tremendous power inherent in science and technology; A power that does not crush people, but propels them forward. If asked what he had to do with Spencer's "social Darwinism" and conservative liberalism, which, like the name of Spencer's book, places men against the state - The Men versus the State - Herzl could have replied that it was not from Spencer that he got the "aristocratic" political view, which abhors the democratic political culture, but who received from him the sympathy for the cooperative movement, for the regulation of voluntary labor relations, for the common ownership of the land, for enthusiasm for industrialization and the scientific revolution; And above all, from whom he got the idea that it was necessary to limit and restrain the intervention of the state in the life of society and the economy. He could have quoted in his letter the article he wrote in August 1893, in which he compared the situation of the factory workers - the "machine men" - to the Jews. It is not revolutionary socialism, he wrote there, that will bring them salvation, but "the scientific revolutionaries (they) are preparing the salvation from the known distress..."

In this article an ambivalent attitude towards the achievements of science and technology is revealed: Herzl wrote in it that the use of electricity will come, but will create a new hardship. The political orators (demagogues), he wrote, supplement the "suffering during a dark night with legends, promises and pleasant or blood-soaked illusions." However, in the long run, the use of electricity - and not politics - will bring salvation. Herzl did not view the processes of urbanization and industrialization with anxiety and horror, in the spirit of the cultural pessimism of the time, and did not describe them as creating "hell on earth." Such a view was shared by, for example, Nahum Sokolov, who described industrial progress as a miracle, leading man to a new era, and Nachman Sirkin, who wrote that technology has changed the world for the better from end to end.

Herzl parted ways with Spencer in his involvement in immigration and settlement planning, which required organization from above. He also separated from him with regard to his view on the need for planning society - an idea he drew from radical liberalism, from Bismarck, and certainly from the extensive utopian literature of his time. However, the principles underlying the society described in "Altneuland" are Spencerian ideas; Ideas about a company that gives the individual full creative freedom in all areas and the creation of a model company.

And what about the connection between progress and morality? The contemporary critique of the principles of positivist philosophy cast doubt on the claim that there is a connection between civilizational progress and social (and international) morality. In her opinion, technology and science have given those with political and economic power new strengths that will only increase the acts of wrongdoing. One can find in Herzl's writings echoes of this dilemma, which occupied many, but he did not deal with questions concerning the "pure moral domain", or with moral behavior on the private level, but with questions related to the construction of society and its social nature. He does not discuss morality as a philosophical question, but the way to establish a just society as a political and social problem. This is the "new morality" that Herzl means. Like Spencer, Herzl believed that it is impossible to enact moral laws based on abstract principles, and therefore, the restoration of the authentic Jewish personality could only be realized in a socio-economic framework guided by rational considerations in the spirit of reason and optimistic confidence in its power. These will create a place where "we can finally live as free people on our land... the place where we too will be honored for great deeds. A place where we live in peace with the whole world..."

In his 1940 article, "If only Herzl were still alive", Martin Buber wrote that Herzl saw technical progress as a renaissance, a cultural revival, and believed that the solution of the social question depended only on technical means. According to Buber, Herzl believed that technology is not just a tool, but that it itself brings the "new spirit", and is the one that will create "an excellent culture and an excellent way of life". But Buber sinned against Herzl. Herzl certainly did not see technology as the "spirit", but as the means to create the necessary conditions for the "renewal of the spirit", for the revival of the vitality of the Jews and for the creation of "authentic life" which will lead to the correction of the "immanent flaws" in the "Jewish soul". However, Herzl believed that "morality" and "happiness" are a product of political and socio-economic order. In Spencer's words, what is good in the moral sense is what is good for the life of both the individual and society.

Herzl's utopia dealt with the possibility of implementing in the Land of Israel the European ideas of progress and establishing a just society, whose moral dimension would be reflected in social behavior. Herzl's "new Jew" was the one who created with the power of reason and imagination, technology and science, a sophisticated society that succeeds in overcoming the internal tensions between capital and labor, between technological and material progress and social behavior - these are the tensions whose existence in European society and their influence on it he described very sharply. Altneuland, Friedrich explains, must be "more than the sum of all its components, and it is indeed more than a combination of technical and social progress. The official at the Ministry of Health explains: "Our new company does not advocate equality. Everyone gets paid according to their labor and work. We did not eliminate the competition, but the opening conditions (are) equality at the starting point" (translated by Miriam Kraus).

This is therefore a revolutionary Jewish and human enterprise that can be realized by means that Nietzsche, but not Spencer either, believed in: means of early social planning - "Everything will be determined in advance according to a well-prepared plan", Herzl wrote in "The State of the Jews". After this plan was put into effect, he could explain in his letter to Spencer, there would no longer be a need for the involvement of the state, which Spencer saw as a major factor in society's degeneration and deviation from the path of progress.

Herzl's belief in the ability of modern man to create - even out of nothing - a "new environment" is therefore an unconditional belief, and there is no hint in his writings that he believed that the immanent qualities of man could also lead the society of the future to a moral retreat, and hence the possibility of realizing a utopia should be questioned. In "Altneuland" Herzl describes a conversation that takes place in the living room of the house of the painter Isaacs in Jerusalem. One of the speakers strongly rejects the pessimistic worldview of Ecclesiastes and claims that this worldview has "gone off the rails"; That is, it passed from the world as a result of the invention of the train - one of the most important instruments of modernization and progress. Those responsible for the flourishing of the pessimistic opinion, he adds, are the socialist tribunes, but it is nothing but a legend and an illusion, since positive values are eternal values. However, Herzl did not explain how his exemplary society would be able to utilize science and technology only for the benefit of society and man. In this respect he was no different from other utopians of his time.

From the point of view of his newspaper "Noya Praia Persa", he was nothing but a brilliant Platonist

By Guenther Haller, Spectrum

"There are two beautiful things in the world: to belong to the 'Neue Freie Presse' (NFP) or to hate it": not many in the Viennese literary scene in the nineties of the 19th century were bold enough to choose the second option. Karl Krauss, who voiced this quip, was one of them: he hated this newspaper, which was the meat of the cultured and liberal Viennese bourgeoisie, and sent half of his satire in it. Most of Vienna's young literary men reacted quite differently. The NFP was a newspaper read across Europe, shaped public opinion and expressed public opinion. You could dedicate your life to an attack on this powerful stronghold, or see your name emblazoned on it alongside famous writers such as Gerhard Hauptmann, Emile Zola, Anatole France, Henrik Ibsen or George Bernard Shaw. The choice between these two options seemed easy. But the road to the destination was full of potholes: those who had not yet bought themselves a reputation and a name, at most managed to sneak into the back of the newspaper, to the literature section. The Holy of Holies, however, was what was called the "playton" on the front page, and dealt with poetry, theater, music, art - to distinguish thousands of differences from the inferior political chronicle. The writer Stefan Zweig once said that whoever was published in "Playton" was as important as the one whose name was engraved in marble in Vienna.

Theodore Herzl also believed in this, who came from Budapest to Vienna in 1878 and is 18 years old, graduated from the Department of Law and wrote travel notes at the time. In October 1887, he wrote to the publisher of "Noya Praia Persa", Edward Bacher, as follows: "I was told," wrote Herzl, "that you expressed great sympathy for my lists that appeared in the Foreign Section; Therefore my request is flat before you, that you give strength to my hand to hold the sword. Perhaps you will find it appropriate, very honorable sir, to allocate a small corner to a happy and kind-hearted employee in the local section or in another internal section." A year later, Herzl wrote to his parents, apparently still not reaching his goal: "I aspire to reach a permanent contract with the newspaper; My security - and my self-security - will not be strengthened until after my first half dozen platoons are published."

It was his ambitious mother who encouraged him to go to Vienna, and instilled in him the ambition to become a "German writer". His planned career path seems clear: to be a playwright, a writer who lives off his writing, a journalist.

For those who were born Jewish, this option, of a literary career, seemed to be the best way to social acceptance and recognition. Already in his youth, Herzl recorded his travels, thoughts and observations. Writing was always his strong point, and his whole life remained tied to the Platonist genre of writing. Every time he tried to go big and try a more ambitious genre, he was much less successful, although it should be noted that he was able to fulfill a dream and put on a play he wrote on the stage of the "Borgtheater" in Vienna.

As the author of light and elegant lists - such are the platons by their very definition - Herzl ironically joined a field that in the Vienna of the late 19th century was considered distinctly Jewish. In fact, everyone who touched this literary form was of Jewish origin. It should not be forgotten that in the early nineties of the 19s the Playton, that distinct product of the "Jewish press", was the target of anti-Semitic attacks. The "German writer" Herzl, who wanted to renounce his Jewish identity, suddenly found himself standing in it.

In 1891, the fort was finally captured: his travel notes from the French Pyrenees aroused great admiration in Vienna to such an extent that the "Noya Praia Persa" system offered him a job as a newspaper reporter in Paris. He signed a five-year work contract and his job was to report on everything that happened in France. But being a man of letters who was only slightly interested in politics, Herzl therefore followed the National Assembly debates in the "Palais Bourbon", and mainly composed quick platoons about Parisian society and cultural life in the French capital. And at the same time, he didn't give up on his literary ambitions either.

Felix Zlatan (he was also born in Budapest and moved to Vienna, Schnitzler's friend and author of the book "Bambi") wrote: "He sent his platoons into the world like they send poached, gifted children wearing vests. They had excellent manners and had the charm of someone who had a polished education." This was exactly the kind of thing NFP readers appreciated. Herzl became the favorite journalist of the Viennese bourgeoisie, and thereby consoled himself for the misfortunes that befell him on the stage of the theater in Vienna. However, the wound did not heal completely: "As a writer, that is, as a playwright," he wrote, "I was considered nothing, much less nothing." They only call me a good journalist." But his readership was immeasurably greater than the crowded crowd at Vienna's "Borgtheater". His analyzes of the feverish and shaky French Republic amid corruption and various varieties of radicalism were read in Vienna and Constantinople, Berlin and London.

The year was 1894. At that time, Herzl saw anti-Semitism as the fashionable evil of French politics. On January 5, 1895, he reported as an eyewitness on the ceremony of removing the ranks of Rabbi Sergeant Alfred Dreyfus. At that time, the affair did not particularly concern him, but it caused a deep political crisis in France: the accusation and conviction of the Jewish officer Dreyfus for the crime of treason was based on forged documents, doubts as to the truth of the evidence were suppressed and eliminated. A process of perverting justice against the background of strong anti-Semitic currents became the talk of the day in Paris and soon spread throughout Europe. Herzl wrote a whole series of articles about the provision for NFP.

But was the Dreyfus affair - as Herzl later claimed - the event that turned the Platonist and author of comedies into the founder of the Zionist movement? Herzl researchers today doubt this. During the trial and demotion ceremony of Dreyfus, no one could assume that he was innocent, and in the diary that Herzl began to write a few months later, describing his journey to Zionism, the Dreyfus trial is not mentioned at all. On September 9, 1899, he wrote the following about the final legal proceedings - Dreyfus was again convicted against expectations - the following: "It has become clear that justice can be denied to a Jew solely because he is a Jew. It was discovered that it was possible to torture a Jew as if he were not a person" - however, at that time, Herzl's Zionist ideological structure was already on its way.

There is no doubt that it was in Paris that Herzl's interest and concern for the Jewish question was awakened and grew. As a reporter for a global newspaper, he was at the heart of the events. Already in Vienna he experienced encounters and confrontations with groups of anti-Semitic thugs and with the followers of Georg Schnerer who advocated extreme German nationalism. But only in France did he encounter that theoretical anti-Semitic superstructure that he had not known until then. Pseudoscientific publications of social Darwinism were bestsellers. Herzl diagnosed that what happened in France would later happen in Austria as well. His conceptual structures on the solution of the Jewish problem can be seen at most, according to Herzl researcher Steven Beller, as "a dialectical consequence of his experience with anti-Semitism in Vienna and his experience with Parisian politics and French anti-Semitism."

Herzl continued to work as a journalist, and in the summer of 1895 he was called to return to the system in Vienna as chief editor of platoons. His most successful play, "The New Ghetto", was put on the stage of the theater and caused a great flare-up of anti-Semitic passions. Only then did he understand in retrospect the meaning of the shouts of the spectators in Paris at Dreyfus' demotion ceremony, "!A mort les Juifs !A mort" (Death! Death to the Jews!). More and more he doubted the possibility of coexistence of Jews and non-Jews on the basis of understanding and tolerance. In the Vienna municipal elections on April 2, 1895, the power of the Christian Socials under the leadership of the anti-Semitic Karl Lueger increased so much that the power of the Liberal Party shrank to a majority of only ten votes. "In a little while," wrote the "Noya Praia Persa" newspaper on election day, which the day before had called on Jewish voters to exercise their right to vote, "and Luger will be mayor, and Vienna will be the only major capital in the world to bear the stigma of anti-Semitic leadership."

Herzl was aware of the trap that the Jews of Austria-Hungary had fallen into: most of the Jews longing for emancipation were stuck in a kind of no man's land. On the one hand, they no longer had roots in Jewish soil, but to that extent the promises of emancipation remained empty of content. In many professions and among most parties they were not welcomed again.

Herzl's Zionism, the idea of a Jewish state as an alternative to the unfulfilled liberal promises, was a logical and consistent answer to a given situation. Herzl did not rule out any solution, starting with knife fights of Jews in anti-Semitism, but also mass conversions of Jews in the Vienna Cathedral. He sent his ideas to his superiors at the newspaper, the Jewish Edward Bacher and Moritz Benedict, the publishers of NFP. The two did not hesitate to return from Paris to Vienna their precious correspondent, who was then appointed - with worse pay and conditions - as the editor-in-chief of the platoons section.

But the star journalist brought new and brilliant ideas to his new role. 37 of the 52 permanent editors at 11 Fichte Street, the headquarters of the editorial board, were of Jewish origin, and more than half of them originally came from Bohemia, Moravia or Galicia. Moritz Benedict, who was for many years the editor-in-chief and publisher, reflects in his biography no less than Herzl himself the typical trajectory of a Jewish journalist at that time.

The Viennese press provided the Jewish intelligentsia with the opportunity to climb the professional ladder regardless of their religion. The press paved a way for them into the lounges of the liberal high bourgeoisie. "Intellectual energy that has not found an outlet for hundreds of years", as Stefan Zweig said, found an opportunity to break out and be fully realized. These assimilated Jews, who distanced themselves in their hearts from the old traditions, which had earned them a place of honor thanks to their intellectual and artistic achievements, now found themselves fellow citizens with Herzl and his vision.

Herzl accurately recorded all of these in his diary; For example: a long walk with Moritz Benedict on October 20, 1895 in the open spaces of the Mauer quarter in Vienna. The subject of the conversation was the situation of Austrian Jews, which had deteriorated to the point of crisis. Herzl wanted to harness the newspaper to his idea of a Jewish state. To this Benedict replied: "You pose a tremendous question to us: the entire newspaper was then an effort of a different perception. Until now we were considered a Jewish newspaper but we never received this definition. Now we are supposed to suddenly give up all disguises." At the end of a week, Benedict gave him a final answer: "If in the foreseeable future we will receive a publicist representation of this position, I do not know, and I believe we cannot guarantee you that. Maybe one day things will come to serious anti-Semitic riots, murder, killing, looting - then maybe we'll have to make use of your idea anyway."

From then on it became clear to Herzl that "for my purposes I cannot expect anything from 'Noya Praia Persa'". Benedict and his accomplice ignored their promise to cover Herzl's book "The State of the Jews" (1896). They also refused to publish Herzl's articles on Zionism. Herzl was deeply disappointed by his newspaper's suppression and ignoring strategy. The publishers saw him as a valuable employee, who had to keep him in his position due to his popularity among readers. But as soon as his Zionist plans came to the fore, confrontations full of irritation and tension broke out between them.

Jewish circles that were then assimilated into their environment strove to dispel the prevalent myth of Jewish groups. To this end, they adopted a neutral anti-Jewish position in Mofagan. Books that dealt with Jewish problems such as Arthur Schnitzler's "The Way to Freedom" (Der Weg ins Freie) or "Professor Bernhardi" were received with displeasure and sourness by the NFP administration.

At the same time as Herzl's reports on the Dreyfus trial in 1893, the "Noya Praia Persa" published interviews conducted by the Viennese writer and playwright Hermann Bacher on the issue of anti-Semitism with international personalities such as the playwright Henrik Ibsen and the socialist August Babel. The result was shocking: all 41 interviewees declared themselves without a shadow of embarrassment as anti-Semitism, or at least claimed that the Jews are partially to blame for the existence of anti-Semitism. Economist Gustav Schmüller spoke against "the mixing and hybridization of races that are physically, spiritually and morally very, very different from each other." He did indeed speak of "Coles, Chinese and Negroes", but to a lesser extent also of the Eastern European Jews. The zoologist Ernst Hakel said there: "I don't want to believe that a powerful, old and large movement (like anti-Semitism) could exist without having a solid causal basis."

Herzl, who was hurt to the core by the alienation of his assimilated environment, actually launched a campaign for Zionism alone. As I remember, he suffered many setbacks but also his first great victory: the first Zionist Congress convened in August 1897 in Basel, at which he said the famous sentence: "In Basel I founded the Jewish state".

About two dozen special envoys of the important European newspapers came to the Basel casino to cover the Congress. Herzl's home newspaper boycotted the event completely and would not single out a single line for it. Shortly before the congress, Herzl founded the Zionist movement's publication, the weekly "Die Welt". Herzl's own name did not appear on the newspaper because he was afraid of jeopardizing his position in the NFP. And it is true that Moritz Benedict warned him in a way that does not imply two faces of what is expected of him if he does this.

In the last years of his life, Theodor Herzl was completely haunted by feelings of fear about the terrible end that awaited the Jews of Europe. On July 3, 1904, the struggle came to an end; He lost the race.

Most of the NFP board members followed his coffin. In the official obituary published by the newspaper, his literary and journalistic talents were emphasized, but the newspaper did not dedicate much space to the matter that was close to his heart and for which he sacrificed himself; Herzl received the greatest praise for his Platonist writing, which he himself saw as nothing more than a source of income.

And yet the newspaper mentioned that it is impossible, and "almost foolish", to talk about Herzl without mentioning Zionism. As the Messiah, it was written in the obituary, Herzl tried to "rescue his people from suffering and torment back to Palestine, the ancient promised land". He stuck to "a beautiful legend from the outskirts of the East."

Translated from German by Aviva Aviram

https://www.hayadan.org.il/BuildaGate4/general2/data_card.php?Cat=~~~898923153~~~262&SiteName=hayadan