A study by researchers at NASA and abroad, published this week in a management journal, provides insights into the need to document events in which luck played a role in order to prevent them, and in particular, the managers should emphasize the importance of the issue among their employees

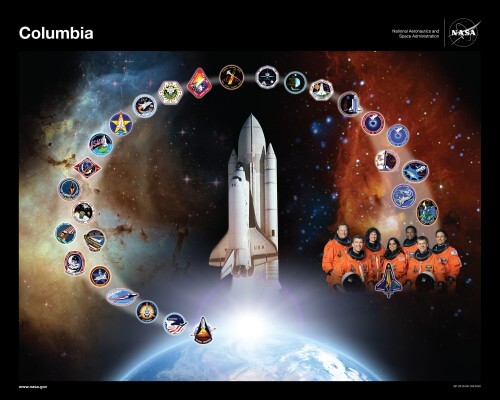

Peter Madsen, a professor of business administration at Beringham-Young University has been researching the safety atmosphere at NASA since the disaster of the Columbia shuttle crash when it entered the atmosphere on February 1, 2003. As you may recall, Col. Ilan Ramon, the first Israeli astronaut, was also killed in the crash.

Specifically, Madsen investigates how it is possible to identify 'near-accident' events, events in which failures were narrowly avoided and apparently the mission was successful. A new study of NASA's safety climate in collaboration with Prof. Madsen reveals that recognition of these 'near misses' increases when the significance of the project is emphasized, and when organizational leaders prioritize safety over other goals (such as efficiency).

In other words, if you want to prevent disasters, your employees need to feel that their work has greater meaning, and they need to know that safety is an important value for their managers. "This feeling challenges people to see something that didn't have a visible negative outcome in a near disaster situation," said Madsen. "It's part of human nature: we mostly tend to consider what happened instead of what could have happened. But this perception can be changed through effective leadership."

Using a database of in-flight anomalies over two decades (1989-2010) in unmanned NASA missions, the researchers discovered that when NASA leadership emphasized the importance of projects and in particular the importance of safety, the organization recognized and investigated near-catastrophic events, instead of dismissing the missions as successful.

The findings, which appear in the Journal of Management, can be applied by company leaders in several industries where safety is of utmost importance, including transportation, power generation, rescue and health.

"If you are in an industry where safety is important and you really want your employees to take it to heart, it is not enough to talk loudly, but also to back up the statement with actions." He said, "Employees are very good at receiving the signals that the managers send to them regarding the order of priorities."

The same was true at NASA over the years, Madsen found that when leaders created a climate of safety and emphasized the importance of investigating near-miss projects, employees cataloged the incidents and could be used to improve mission operations. Unfortunately, Columbia took off at a time when NASA's reported near-miss rate was among the lowest

The investigation into the crash revealed that the failure that caused the disaster (the spectacular foam fall) happened in at least seven previous launches. In each of them, luck intervened, and the near misses turned into successes.

The commission of inquiry into the Columbia disaster found that NASA's poor safety climate was the main cause of its people's inability to recognize the falling of the foam as a near-catastrophe, and that in the collision between the goals of cost, schedule, and safety, safety lost."

"A lot of safety improvements happened after a disaster and they shed light on the deficiencies in the system," Madsen said. "If you can pick up on these deficiencies before something happens, that's the gold standard."

Madsen's NASA connections go back to the time of Columbia's loss, when he was in graduate school at UC Berkeley. His research advisor was a well-known expert in safety organizations, which led to Madsen and other PhD students who were assigned to work with NASA to research safety procedures.

He continued his ties to NASA since Edward Rogers, Chief Knowledge Officer at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, is a co-author of this study. Robin Dillon of Georgetown University's School of Business Administration.

"Many safety improvements occurred after the disaster and they shed light on the deficiencies in the system," Madsen said. "If these defects could be overcome before something happens, it should be the gold standard."

Madsen's ties to NASA date back to the days after the disaster, when he was doing his Ph.D. at Berkeley. His supervisor was a well-known safety consultant, which led Madsen and another doctoral student to work with NASA to investigate safety procedures. He continued his contacts with NASA and Edward Rogers, the Chief Knowledge Officer at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, also participated in the research. The third partner was Robin Dillon from the Georgetown University School of Business.

Ham wrote together with Yaffe Shir-Raz the book "The Crash" which documented the Columbia disaster and the conclusions that were formed even then.

Chapter: Was NASA's organizational culture at fault for the shuttle Columbia? (from "The Crash")

The good ones for the pilot - a chapter about the late Ilan Ramon from the book The Crash

5 תגובות

Haim Mazar

In my job, we are obliged to work in a system that was developed together with Eli Goldert years ago. The critical points are disastrous for the project, bottlenecks in everyday language.

But - I think I understand your point. It is worthwhile (obligatory!) to look for such points that have safety significance, and manage them as you manage everything else in the project.

I read Feynman's investigation at the time. He said something like: "NASA estimates the probability of an accident at one in 100000 and I estimate it at one in 100." Beyond that, engineers also thought like him.

Here - I found the source:

It appears that there are enormous differences of opinion as to the

probability of a failure with loss of vehicle and of human life. The

estimates range from roughly 1 in 100 to 1 in 100,000. The higher

figures come from the working engineers, and the very low figures from

management. What are the causes and consequences of this lack of

agreement? Since 1 part in 100,000 would imply that one could put a

Shuttle up each day for 300 years expecting to lose only one, we could

properly ask "What is the cause of management's fantastic faith in the

machinery?”

What a shame he was still a bit of an optimist...

Miracles

As an addition to my answer, you rightly claim: "But if people don't live the world they work in, then no book of procedures will help." It belongs to an organizational culture that is appropriate and even important to check both regularly and during the work of investigative committees.

Miracles

As I recall, in the theory of constraints, critical junction points are located in the planning of the production process and thus identify potential problems that could be disastrous (a subject on which I published an article years ago in the journal "Status" (by the way, I also publish articles on organizational consulting. You can see them in the journal) Human Resources" and in the magazine "Managers" in which I wrote a lot until its closure). It is possible that using the theory of constraints would have illuminated critical junction points in the production process and thus saved the Challenger disaster and the Columbia disaster. Richard Feynman wrote about the Challenger disaster I don't remember where it appears in the magazine "Galileo" or in the magazine "Management" (this magazine was also closed). Anyway, the article was translated into Hebrew.

As a side note, locating critical junction points not only saves money during the day-to-day work. It locates those problematic points that can cause severe to irreversible damage. Such damages mean loss of revenue and loss of reputation. Then it is necessary to establish commissions of inquiry and this costs a fortune. So the saving of money is not only in the current, but also in the prevention of expenses in case of a very heavy defect. The money saved could be invested in other important places as well.

Haim Mazar

I have been working for many years in the theory of constraints method and I do not know anything related to safety. The theory of constraints (the one I know) talks about saving money.

The problem, as described in the article, is not procedural - the problem is human. Procedures can certainly help but if people don't live the world they work in then no library of procedures will help.

my father

One gets the impression that the management side is not one of the best in the N.A.S.A. And in particular with regard to quality control and they did not make any use of the theory of constraints. This is a Torah that deals with the management of the management process. The definition I give to this theory is extremely limited so that I don't have to write a text book.