Newly discovered Mayan artwork tells of an ancient conflict

The king sat in darkness for more than 1,400 years. When archaeologists discovered it, half of its artist-engraved face was missing, but the richly detailed crown and symbols of rule were still intact. He kept one eye on the dark tunnel the new visitors had let inside one of the largest structures in the ancient Mayan city of Holmul in present-day northeastern Guatemala. Hieroglyphs engraved next to the figure revealed its name: Och Chan Yopaat, or "Storm God Enters the Sky".

A spectacular tablet, discovered in the ancient Mayan city of Holmul in Guatemala, helps archaeologists understand how the Mayan states functioned during the long war that defined the history of this culture for more than a thousand years.

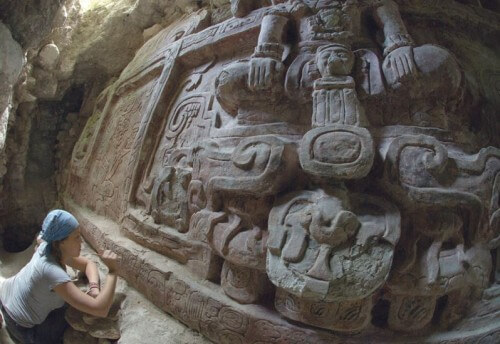

The king is the central figure in a sculptured tablet that was recently discovered and which excites the archaeologists studying the Mayan culture. Francisco Estrada-Belli of Boston University excavated a rectangular pyramidal monument on whose upper surface ceremonies were held, to learn about the political movements during a very tumultuous period in Maya history. Inside the pyramid are the remains of all the buildings that stood in that place hundreds of years before larger temples were built on top of them. When Estrada and his team dug tunnels through the structures to explore the remains of these ancient sites, they came across the base of a staircase. In the summer of 2013, they went up the stairs to the front of a temple that is nine meters high, and miraculously it was not destroyed. The magnificent panel, which is eight meters wide and two meters high, is made of carefully carved plaster, and was used as a frieze, which decorated the entrance doorframe of the temple.

But the frieze is more than just decoration. This is a historical document, which helps archaeologists understand how the Mayan states functioned in times of revolution. At the time when the tablet was created, around 590 AD, Holmul was at the center of a conflict that, according to many researchers, characterized Maya history for more than a thousand years: the war between the kingdoms of Tikal and Kaanul. The experts believe that the king seen in the center of the panel is the founder of the dynasty that ruled Holmul during that crucial period. If the hypothesis is correct, the discovery will help answer some questions about the Mayan administration, which have not been answered so far.

written in plaster

The reason for the protracted war has been lost in the depths of time, but many researchers believe that it is related to wealth resources. The rulers of Tikal and Kaanul probably fought for the control of trade routes for products such as volcanic glass for building tools and weapons, jade stones for creating sacred objects and cocoa beans that were used both as currency and as the main ingredient in a chocolate drink that was drunk during religious ceremonies. Holmul was just one city out of dozens or hundreds of cities that created a trade network and channeled the economic prosperity of the region to the capital city of the kingdom to which they belonged at the time. However, Holmul is especially important to archaeologists due to the wealth of information preserved in its ruins - both about the site itself and about the politics of the time.

The analysis of the temple and its magnificent frieze has not yet been completed, but Estrada-Belli and his colleagues have already begun to uncover the plot it reveals about the city of Holmul at a crucial time in its history. One of the uses of the Mayan rulers for the enormous wealth they accumulated was the construction of large buildings, designed to please the gods and the spirits of important ancestors who made this wealth possible, and to ensure their continued support. The temple in Holmul apparently served exactly this purpose: decorations on the sides of the building identify it as the "house of the royal dynasty" - a place of worship for the ancestors of the ruling family.

To help decipher the wealth of symbols on the tablet itself, Estrada-Belli enlisted the help of Carl Taube, an expert on Maya iconography from the University of California, Riverside. Taube noticed that the king in the center of the panel was sitting on top of a mythical mountain god named Weitz. Caves found on the slopes of this mountain serve as passages to the world of the dead, as well as a source of rain and wind. The king sits above a cleft at the top, and two feathered serpents, representing the wind, emerge from the corners of Witz's mouth. "I think they mark the king here and associate him with a holy place, perhaps a place of origin," says Taube, noting that "the rift is the place from which the ancestors come out" from the world of the dead. The Mayans believed that under the earth and under the water was the home of the dead, and also the abode of many evil supernatural beings. Caves therefore served as a transition between the world of the dead and the world of the living.

Around the king stand figures representing death and night. According to Taube, these are the jaguar gods of the underworld: since the jaguar is a nocturnal predator, different groups of the Mayans attributed a variety of meanings to it. The jaguar represented the sun at night, as it passed, it was believed, in the land of the dead. It is interesting to note that usually, kings in Mayan artwork are shown making sacrifices to the gods, whereas in this panel it is the jaguar gods who are making a sacrifice to the king. It is not clear why the roles were reversed here, but it makes King Uch Chan Yopaat (and hence the ruling family) seem important.

However, a set of hieroglyphs at the bottom of the board adds an interesting twist to this story of self-aggrandizement. According to Alexander Tokovinin, an engraving expert from Harvard University who translated the ancient script, it is written there that the temple was built at the request of a king from a larger and stronger neighboring city, called Naranjo. The writer identifies the king of Naranjo as the one who restored the royal dynasty of Holmul, but also as a serf or ruler subordinate to the supreme ruler of Kaanul. Therefore, even if the paintings glorify King Holmul's place in the universe, the inscription reveals that he actually stands at the bottom of a three-step hierarchical ladder. The king of Holmul was a serf of the ruler of Naranjo, who in turn was a serf of the supreme ruler of Kaanul. "Which shows that the Maya kingdoms were interconnected," says Estrada-Belli, "We didn't know where Holmul was on the Maya geopolitical map until this inscription revealed it all."

war forever

The information on the board is added to a growing list of evidence, contradicting the traditional perception of the Maya as a peace-seeking people. In the years 1995-2000, Simon Martin from the University of Pennsylvania and Nicolai Grobe from the University of Bonn in Germany deciphered and mapped the power relations in the Mayan kingdom, as recorded on buildings throughout the kingdom, from southern Mexico to northern Honduras. The research showed that war was a common affair, and that each city had a place in a rigid hierarchy. The various kings were ostensibly independent, but in fact all were subordinate to the Tikal or Kaanul dynasties. "These were apparently the superpowers of the Maya, who ruled with hegemony over all the other Maya kingdoms," Estrada-Belli explains.

"The question [at this time] was which of the two kingdoms would be at the center," says Martin. By the middle of the sixth century, Tikal seems to have had the upper hand. The strong connection with the city-state of Teotihuacan in central Mexico helped Tikal expand its range of influence eastward, to the Yucatan Peninsula and the Peten region of northern Guatemala. The city of Teotihuacan collapsed in about 550, and in 562 Tikal suffered a crushing defeat in battle, and as a result no large buildings were built in the city for more than 130 years. During this period, the Kaanul rulers began to expand the scope of their rule in the region. One of the cities that the Kaanul dynasty took over at that time was Holmul.

According to Estrada-Belli, the fact that the Holmul dynasty was "restored to power," as the inscription on the tablet suggests, shows that the city was previously occupied by Tikal, probably around the fifth century AD, and the ruling family was dethroned. When the Kaanul Kingdom recaptured the city, it restored the old order. Tokovinin interprets things in a different way: he believes that the rulers of Naranjo transferred their loyalty from Tikal to Kaanul, and brought Holmul with them. One way or another, Holmul's strategic location, between the capital of Kaanul in the north and the city of Tikal in the west, made it an important asset.

The king of Holmul was indeed subject to the lord of Kaanul, but in some ways he was free to do as he pleased. Unlike the empires of Rome or Egypt, which directly ruled the lands they conquered, the Mayan powers preferred to let the local authorities continue to rule, as long as they raised taxes. According to Martin, "They wanted to create relationships of subordination. There is no doubt that economic gains were of interest to them, but they were not particularly interested in establishing riot police and expanding their own territory. In this sense, it is a very decentralized picture."

Superpower or empire?

The decentralized nature of Maya government is at the heart of a debate over whether the states of Tikal and Kaanul were superpowers or empires. According to Martin, the geographical areas under their control were too small, the entire Maya domain was the size of New Mexico, and their control over the subordinate kingdoms was not stable enough to compare with the empires of Europe, Africa and Asia. Martin prefers the term "superpower" for these small and unstable countries. Estrada-Belli disagrees with him: he believes that monuments like the Holmul tablet clarify the power relations between the cities, and now it is easier to say that the Maya had empires. "It's time to change the paradigm," he insists, "the Maya look more like a culture that at one time was headed by one king, like for example, Kaanul in the period in question here, so it is very similar to some of the great civilizations of the old world."

Determining whether Kaanul and Tikal were superpowers or empires is important to understanding how they functioned on a day-to-day basis, and why they went to war so often. In both cases, it is likely that Holmul paid some kind of tax to Naranjo, which in turn raised a tax to the Kaanul ruler. What is not clear from the archaeological evidence is what Holmul received in return.

"There was something here that sweetened the pill," believes Martin. In his opinion, it is possible that Holmul's elites received exotic gifts and were invited to attend feasts and conduct ceremonies in the capital of Kaanul, as a means of encouraging them to cooperate with Kaanul's ambitions.

David Friedel of Washington University in St. Louis has a different view of this relationship. He believes that the taxes that the Kaanul rulers demanded from their subject kingdoms created a mostly one-sided economic relationship. "The resources, including goods and fighters for the incessant battles, all flowed towards the capital cities of the two superpowers," he says. "There is no doubt that it was exploitation."

Friedel, who participated in the management of excavations in one city that was subordinate to Kaanul, believes that the Mayan states were similar, in many ways, to other countries around the world that erected monuments to the glory of their leaders, the pyramids in Egypt, for example, or the triumphal gates in Rome. "They liked the aesthetics of power," he says. "It is found in all cultures. This plaque serves as an excellent example, and they buried it because it was beautiful and they wanted to preserve it and its memory." It is possible that the Maholmul tablet was buried so as not to upset the gods and the ancestors who appeared on it when an even larger monument was built over it. In this way, the rulers of Holmul could continue to build large new buildings and still preserve, in a certain sense, the old buildings.

According to Friedel, he accepts most of Martin's and Grube's interpretations of the new tablet, but as archaeologists learn more about the history of the Maya states, they look more and more like empires. It is possible that the solution to the differences of opinion will come, among other things, from the continuation of the excavation in the buried temple of Holmul. Estrada-Belli plans to continue excavating the tunnel around the rest of the building, exploring two newly discovered rooms inside the temple and exposing its outer walls. The slab, large as it was, only covered the top of one side of the structure. There may be many more decorations on the monument, which will provide more information about Holmul's fate during the ebb and flow of the centuries-old battle between these ancient nations.

in brief

An archaeological dig in the ancient Mayan city of Holmul, in Guatemala, has revealed a decorated and detailed tablet that sheds light on an important chapter in Mayan history. The plaque appears to depict the founder of the ruling dynasty of Holmul, a city that was at the heart of a bitter conflict between two superpowers. The decoration, rich in symbols and inscriptions, contains clues that researchers have been looking for for a long time, about the administration in the Mayan lands during this important period.

About the author

Zak Zorich (Zorich) is a freelance writer from Colorado, and editor of Archeology magazine.

More information

Remote Sensing and GIS Analysis of a Maya City and Its Landscape: Holmul, Guatemala. Francisco Estrada-Belli and Magaly Koch in Remote Sensing in Archaeology. Edited by James Wiseman and Farouk El-Baz. Springer, 2007.

The article was published with the permission of Scientific American Israel

More of the topic in Hayadan:

One response

Is it always the case that people invent different types of positions just to exploit, trample and advance at the expense of the other? It is clear that this way is outrageous and will become extinct in the long run.

Can someone come up with another method where everyone benefits without harming others or the environment?