In the early nineties of the 19th century, aviation was considered one of the most promising fields in science. The technological developments appeared one after the other and it was clear to everyone that it was only a matter of time before someone would be able to fly

In the early nineties of the 19th century, aviation was considered one of the most promising fields in science. The technological developments appeared one after the other and it was clear to everyone that it was only a matter of time before someone would be able to fly.

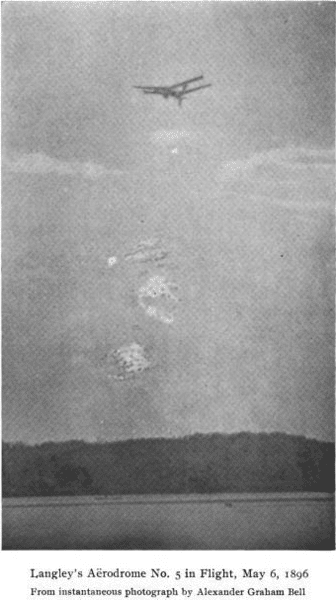

Professor Samuel Langley was the right man at the right time. He was one of the most important and influential scientists of his time: although he had no formal education beyond high school, Langley was sharp enough to become a senior physicist and astronomer, and in 1887 was appointed director of the Smithsonian Museum in Washington. It is worth noting that the director of the Smithsonian, at that time, was considered much more than 'another director of a public institution': it was a position of national importance, and the directors of the museum were almost ministers of education in the government. This fact will be important later in our story.

Samuel Langley, the Wright brothers and several dozen or hundreds of other inventors all over the world were in the middle of a race, and as in any race - here too there can only be one winner. The only question was - who would it be...

The US military, at least, had no doubt about which horse to bet on. Langley was not only a brilliant and privileged scientist, but also had all the resources of the great museum at his disposal. The Ministry of Defense offered him 50,000 dollars, a considerable amount in those days, to finance the continuation of the research.

Langley accepted the challenge. He turned to an engine manufacturer and asked him for an internal combustion engine - a relatively new invention in those days - that would produce twelve horsepower but weigh less than fifty kilograms. The manufacturer did his best, but failed to meet the requirements. Fortunately for Langley, at exactly the same time a brilliant mechanical engineer, fresh out of university, named Charles Manley joined his team. Manley managed to do what seemed unbelievable at the time: he developed an engine that produced a hundred horsepower, and weighed less than a hundred kilograms! It was a fantastic technological leap, and the Manley engine became the dominant aircraft engine for decades afterward.

In 1903, Langley finished a series of successful experiments he conducted on scale models. Normally, the meticulous and careful Langley would also perform advanced experiments on full-sized unmanned aircraft - but this time he decided to abandon the caution and meticulousness. Perhaps it was the pressure from the Ministry of Defense to provide the goods, or perhaps the knowledge that other inventors were working at the same time as him and might obtain it - whatever the reason, Langley skipped a few steps and built a full-sized plane that was more or less a scaled-up replica of the original models.

On the seventh of October, 1903, everything was ready for the great experiment. The means of launch that Langley used was a powerful catapult that would throw the plane forward and give it initial speed. Langley placed the catapult and the plane on a large raft in the middle of the Potomac River, a location chosen because of the weak winds that blew there.

The pilot was none other than Charles Manley, the engine designer. Manley entered the plane and waved goodbye to Langley and the other spectators. The catapult was pulled back and the spring that was connected to it stretched and stretched...until it reached the end of its travel. Langley pulled the appropriate handle. The catapult rose quickly and the plane surged forward at once.

The first catapults that Langley used were designed for scale models, on the order of a quarter of the size of a real airplane. Since the plane was now bigger, the new catapult also had to be bigger - but it too was never thoroughly tested in controlled experiments. One of the wings hit the catapult, broke, and the plane crashed into the river like a 'handful of stones', as Langley himself defined it. Manley was rescued safely from the sinking aircraft.

The failure of the test was a painful blow to Langley, but he returned to the lake two months later with a refurbished plane. Again Manley climbed into the cockpit, again the catapult was pulled back, again the springs stretched, again Langley pulled the operating handle... and this time, not only the wing but the entire plane disintegrated in the air. Manley barely got out of the water, just before he nearly drowned. It is likely that the reason for the disintegration is that the plane's frame could not withstand the rapid acceleration exerted on it by the catapult. The scale models functioned successfully, but Langley was wrong in assuming that the same basic structure would also be suitable for a much larger and heavier aircraft.

The position of director of the Smithsonian Museum was, as mentioned, a position of considerable governmental and public importance. The opposition in Congress took advantage of Langley's resounding failure to attack the government for 'wasting public money': eloquent speeches were made in the House of Representatives, queries were submitted, the newspapers published painful reviews... Samuel Langley was very hurt by the criticism and decided to abandon aviation efforts, for good.

In a report prepared by the Ministry of Defense on the results of Langley's experiments, it is stated that achieving the goal of manned flight is still many years away from being realized. A week and a half later the Wright brothers managed to fly.

Why did the Wright brothers succeed where Langley, the privileged professor, failed?

One of the most important reasons, and perhaps the best known of all, was the steering system that the brothers designed for their plane. The simple balances added at the ends of the wings gave important stability to the aircraft, even under the effects of winds, etc.

Another important reason - and often unknown - is their propeller. Many inventors assumed that the propeller in the airplane should be the same, more or less, to the propeller of a ship or alternatively to the blade of a windmill. Averill and Wilbur realized that an airplane propeller, just like the wing, needs to produce lift - so they designed the shape of the blades to produce the greatest amount of lift, just as they designed their airplane wings. The Wright brothers' engine was a very weak engine, much weaker than Charles Manley's engine - but their propeller was seventy percent more efficient than the propeller chosen by Samuel Langley. If they hadn't improved their propeller so dramatically, it's likely that their plane wouldn't have been able to lift off the ground.

The fight between the Wright brothers and Samuel Langley for the crown of 'the first pilot' did not end with their successful flight - nor even with Langley's death three years later.

At the Smithsonian Museum they maintained loyalty to their former director and tried to rewrite history in favor of the boss. On the explanatory plaques in the museum it is written that Langley's plane, when remembered it disintegrated immediately upon takeoff, was the first aircraft that was 'capable of flying'. It's not the same as 'the first aircraft that actually flew', but that's the fine print, you know.

In 1914, industrialist and aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss took Samuel Langley's original airplane and successfully flew it a few hundred meters. He did this for purely personal reasons: the Wright brothers sued him for infringing a patent related to their airplane, and he wanted to prove to the court that their patent was invalid because Langley had done it first. The Smithsonian used Curtis's success to continue to claim that Samuel Langley was able to build an airplane that was capable of flying - as if Langley could have flown before the Wright brothers but just didn't feel like it... The Smithsonian 'forgot' to mention, however, that Curtis had to make several significant changes to the original airplane to make him rise above the ground.

In the end, historical truth prevailed over ego games. In 1948, the Smithsonian Museum apologized to the heirs of the Wright brothers and officially acknowledged that they were the ones who inaugurated the age of aviation. The Wright Brothers' airplane is currently one of the Smithsonian's most important and popular exhibits.

[Ran Levy is a science writer and submitsMaking history!', a podcast about science, technology and history]

3 תגובות

Towards the turn of the 19th century there was probably a group of people who developed airplanes and even made flights. I wrote about that. A link is attached.

http://www.yekum.org/2012/10/%D7%A1%D7%A4%D7%99%D7%A0%D7%95%D7%AA-%D7%90%D7%95%D7%95%D7%99%D7%A8-%D7%91%D7%A9%D7%9E%D7%99-%D7%90%D7%A8%D7%94%D7%91-%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%93%D7%9E%D7%99%D7%94%D7%9D-%D7%A9%D7%9C-%D7%94%D7%90%D7%

Very interesting. Thanks.

The Wright brothers actually invented the theory of flight, and that's their genius.