Africa's population growth projections are alarming. The solution: empowering women/Robert Engelman

The article is published with the approval of Scientific American Israel and the Ort Israel network

in brief

- By 2100 the number of people living in Africa may reach 3 to 6.1 billion people, a sharp increase from the 1.2 billion people living there today. And this, if the birth rate remains as high as it is now and does not slow down. This unexpected growth will burden the resources of Africa and the resources of the entire world, whose sustainability is already precarious.

- A real decrease in productivity can only come by empowering women at the level of education, in the economy, in society and in politics. They should also be given easy access to contraceptives at an equal price for everyone. With such a combined strategy, Mauritius managed to lower its fertility from 6 to 1.5 children per woman and the fertility in Tunisia dropped from 7 to 2.

- Men must give up their sole authority in deciding whether to have children, and avoid harming women and female partners who choose to use contraceptives.

- In order for these efforts to ultimately succeed, the leaders of the countries must encourage discourse in the public and in the corridors of government regarding the slowing down of population growth.

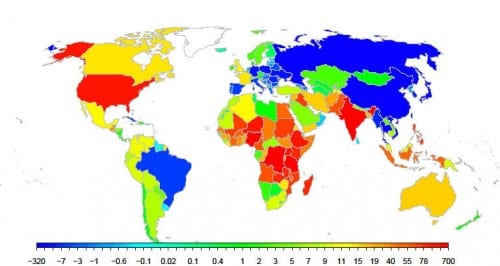

The size of the earth is finite. The more people live in it, the more they are forced to compete for its resources. In view of the accelerated pace of human population growth, there is a fear of a population explosion and its consequences, but the developments in recent decades give rise to hope that we will be able to prevent this. Women in the world today give birth to an average of 2.5 children, half of the average in the early 50s. In 20% of the world's countries, the fertility rate is equal to the level of intergenerational turnover, and stands at 40 children per woman, or less than that. The population of these countries therefore maintains a constant size.

On the other hand, in Africa women give birth to 4.7 children on average, and the population grows at a rapid rate, almost three times that of the rest of the world. This continent, which is the cradle of humanity, therefore faces a worrying future. Fertility - the number of children a woman gives birth to during her lifetime - is still high in most of the continent's 54 countries. Africans have always considered a large family important, both in terms of status and as a way to increase the number of working hands in the family, and to overcome the high early childhood mortality. But today, more babies survive and become parents themselves. More than half of the continent's population, numbering about 1.2 billion people, are children or teenagers. This ratio is a lever for years of expansion at an unprecedented rate in human history. Demographers predict that by the end of the 21st century the population of Africa will triple or quadruple.

For years, the accepted predictions were that the population of Africa would number about 2 billion people in the year 2100. These models assumed that productivity would decrease rapidly and fairly consistently. Instead, fertility rates fell slowly and irregularly. Today, the UN predicts 3 to 6.1 billion people in 2100 - incredible numbers. Even the cautious estimates of institutions such as the "International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis" in Austria speak of 2.6 billion people. In recent years, the UN has come back and raised its forecast for the world's population in 2100 again and again. In 2004 they talked about 9.1 billion and today about 11.2 billion. Almost all of the unexpected addition originated in Africa.

The rapid growth threatens the development of Africa and its stability. Many of its inhabitants live in countries that are not blessed with fertile soil, water or properly functioning governments. The growing competition for sources of food and employment in these places could cause instability in the entire region, which would put heavy pressure on food and water resources and natural resources throughout the world, especially if Africans are displaced from their countries en masse, which is already happening. About 37% of young graduates in sub-Saharan countries say they want to move to another country, mainly due to the lack of employment.

Africa needs new policies that will slow down its population growth, to maintain peace and security, improve economic development and protect environmental sustainability. And the countries of the world should support these efforts. From the 60s to the 90s, international institutions and aid organizations urged African governments to "do something" in the face of rapid population growth. Usually, this "something" is reflected in investing in family planning programs without combining them with other health services, and in government statements that "everything that adds up diminishes" when it comes to family size. But since the mid-90s, there has been silence on the subject. Defining population growth as a problem was accepted as culturally insensitive and politically controversial. International donors turned their attention to promoting general health reform, including the fight against AIDS and other deadly diseases.

Africa and the rest of the world must therefore restore the sense of urgency. We need to overcome the fear of being seen as politically incorrect and initiate some coordinated moves that can lower the slope of the population growth curve in Africa and anywhere else where it is growing in a way that threatens sustainability. Studies show that besides the concern that women have access to effective contraceptives and have the necessary knowledge to use them, the best measures are measures that also make sense for other worthy reasons: educating girls and women and comparing their social and legal status to that of men. Although there are countries in Africa that have already taken some of these actions individually, a much more effective approach would be to combine the opportunities that will open up for women: in education, economy, society and politics.

It is impossible to "control" the population. This is a fundamental violation of human rights and it is likely that any such attempt will not succeed. But it is possible to influence a population in indirect but highly influential ways. A wise choice of strategies can ease the burden on resources, reduce conflicts, and improve the fate of girls, children, women and men.

Africa today and tomorrow

According to many estimates the situation in Africa is already gloomy. Despite the progress in the economy and democracy, the continent today stands out for its low life expectancy, slow rate of development and high rates of poverty and malnutrition. The agricultural yield is one of the lowest in the world. South of the Sahara, overgrazing by sheep and cattle is increasing the spread of desert and pushing nomadic herders into farmland as the populations of both groups grow. Egypt and Ethiopia brush swords over the waters of the Nile, which the 11 countries living in the river's basin used to divide without difficulty. A 2010 analysis found that all four countries where "water security" is the lowest in the world are in Africa.

Competition for dwindling resources exacerbates civil conflicts and terrorism. In July 2014, on the island of Lemu belonging to Kenya, 80 people died in a fight between Muslims and Christians over fertile land. Some researchers attribute the rise of the brutal Islamist organization Boko Haram in Nigeria, at least in part, to the drying up of the Sahel's desert lands. The paucity of livelihood that hovers over the heads of boys and men in their 20s fuels aggression in Central Africa as well. "If there were more jobs, especially in agriculture, there would be less frustration and there would be less conflict in the Nigerian plateau region," says Becky Oda-Donto, an adviser to the Nigerian government, referring to a jurisdiction in the east-central part of the country, the area of activity of Boko Haram.

Four African countries: Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia and the Central African Republic, were ranked by the "Peace Fund" from Washington in the lowest place among all the countries of the world in terms of their stability, their ability to govern in their sovereign territory and their ability to guarantee a minimum level of security for their citizens. Only in 2015, hundreds of Africans drowned trying to escape to Europe.

Now imagine what Africa will look like when it has two billion inhabitants, and we don't have to say six billion. History does not teach much. Asia crossed the threshold of four billion people in 2007, but its area is about 50% larger than the area of Africa and the level of economy and development is higher on average. And yet, despite all its advantages, large parts of Asia are still faced with depleting fertile soil, with a drop in the groundwater level and with food insecurity and severe air pollution.

One huge change that will take place in Africa will be the growth of huge cities. Urbanization in Africa is rapid. Most of the people who come to the cities come from backward agricultural areas, settle in poor suburbs and struggle to find shelter and livelihood in them. More than a billion people live in volumes today. By 2050, more than 1.3 billion will live in them according to UN forecasts. Demographers Jean-Pierre Gungant from the Institute for Development Research in France and John May from the Population Registry Institute predict that the continent's largest cities will experience a population explosion by 2050: the number of residents in Lagos in Nigeria will increase from 11 million in 2010 to 40 million in Kinshasa in the Republic of the Congo from 8.4 million to 31 million. The photographs surveying Kibera in Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, the largest slum on the continent where half a million to a million people live (the number is not confirmed), seen in a scene in the movie "The Dedicated Gardener" from 2005 provide a glimpse of this future. Kibra's corrugated iron roofs stretch to the horizon in every direction. According to current projections, hundreds of communities of similar size will be formed across Africa by mid-century.

The prospect of a dense, conflicted and urban continent has begun to worry African leaders, who have generally tended to support population growth, and are beginning to speak out. In 2012, the then Prime Ministers of Ethiopia and Rwanda called for new efforts to expand the use of family planning to "reduce poverty and hunger, preserve natural resources and adapt to the consequences of climate change and environmental degradation." The president of the International Women's Fund, Musimbi Kanyoro, born in Kenya, recently called for "culturally appropriate and rights-based ways to slow population growth, while increasing human dignity and calculated development."

It is therefore no wonder that making family planning accessible is one of the steps that is receiving renewed attention. Today only 29% of married African women of reproductive age use modern contraceptives. In the other continents their rate is clearly higher than 50%. Surveys also show that more than a third of pregnancies in Africa are unplanned. In sub-Saharan Africa, 58% of women aged 15 to 49 who are sexually active and do not wish to conceive do not use modern contraceptives.

Dejanaba, a girl I interviewed a few years ago, testified to this tension in remote Kfar, Mali, a country where only one in ten women uses contraception. She had only crossed the middle of her second decade of life, and was already a mother of two. When I first asked how many children she would like, she looked down and replied "as many as possible." But after half an hour of conversation, she looked straight into the saucer in her eyes, and said that she would like to take birth control pills, to rest a little from having children and even stop it completely soon.

Any transition to economic prosperity requires a significant decrease in productivity. But this "can only be achieved if the prevalence of contraceptives increases substantially from its current low rate, to 60% by 2050," Gungant writes in a 2013 article. "And it won't be easy to achieve."

First successes

The trend of urbanization on its own may slightly reduce the size of the family. In the city it is more expensive to raise children, and the chances of them contributing to the family income are lower. Also, in the city, the parents' views are more likely to change from a traditional position to modern ideas regarding family size and planning. Ironically, there are some countries in Africa where the fertility rate is considerably lower and lessons can be learned from them. The most important lesson from those countries is the benefit of combining the accessibility of family planning with efforts to give women more control over their lives and families.

In the northern, Arab part of Africa and in South Africa and the neighboring countries, fertility rates have dropped to 3 children per woman or less and they are approaching the fertility rate in the rest of the world. In contrast, in three extensive sub-regions - East, Central and West Africa - fertility ranges from 4 to 7 children per woman and even more.

In the African countries where a reduction in productivity was evident, the work began years ago. In half a dozen small island countries of Africa, the small families live on the continent. One of the fastest declines in productivity occurred in Mauritius, east of Madagascar. The average dropped from more than 6 in the 60s to 2.3 children per woman two decades later. Today the rate there is about 1.5 children per woman, close to that of Europe and Japan. The sharpest decline happened in the 60s and early 70s when there was no economic growth at all. The inhabitants of Mauritius, women as well as men, were relatively educated. And in the early 60s, the national government overcame objections from several groups, including Catholics and Muslims, and successfully promoted family planning. Within two decades, four out of five women of childbearing age used contraception.

Image of a local worker in Shompula, Kenya, explaining to young Maasai mothers how to use a condom.

Community health workers are often the ones who help change people's minds. A local worker in Shompula, Kenya, explains to young mothers from the Maasai tribe how to use a condom.

Picture of a guide in Lanier, Senegal, explaining how an intrauterine device works.

A guide in Lanier in Senegal explains how an intrauterine device works.

In 1957, Habib Bourguiba, the president of Tunisia, initiated a wave of changes in the legal status and reproductive rights of the country's women, changes that are hard to imagine in a country that is majority Muslim. Bourguiba promised women full civil rights, including the right to vote and remove the veil. He committed to compulsory primary education for both girls and boys, banned polygamy, raised the minimum age of marriage and gave women the right to divorce. He brought contraception into the legal framework and then subsidized abortions for women with many children. By the mid-60s, mobile family planning centers were already providing birth control pills across the country. Bourguiba was not a democrat. The "National Council", which was under his tight control, elected him president for life in 1975. But the social reforms he introduced remained in force even after he was ousted in 1987. Fertility in Tunisia dropped from 7 children per woman to 2 in the early XNUMXs (it has risen slightly since then). Somewhat less dramatic and later examples of presidential leadership have helped lower productivity in Kenya, Ghana and South Africa.

Mauritius and Tunisia teach that the secret to reducing family size is a consistent focus on improving women's living conditions, including economic and legal opportunities as equal as possible to men. Because national economic growth alone does not reduce productivity sufficiently.

integrated strategy

How can the other African countries reproduce this success? The first step is to recognize that women and couples, not governments, have the right to decide how many children to have. Women, whose governments and environment treat them as equal to men, are more likely to come to the conclusion that they are the ones who should decide if and when to get pregnant, and the result will be smaller families.

Education, especially in high school, fuels this empowerment greatly. Through education, girls and young women can be taught about nutrition, medicine and vaccinations. But education also opens up a variety of possibilities: economic, social, civic, political and artistic. Education encourages young people to use contraceptives and plan small families while learning about the world, their bodies and the ability to determine their own destiny. Uneducated African women give birth to an average of 5.4 children, according to the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. For women who finished elementary school, the average is 4.3. For female high school graduates, a large decrease in the number of children is evident: an average of 2.7. And for women with an academic education, the average is 2.2.

Improving the education of young men is also essential. Young people of both sexes, who participate in comprehensive sex education programs, are more likely to delay the initiation of intercourse, and this reduces the rate of unwanted pregnancies at a young age. The AIDS epidemic spurred the expansion of sex education, at least in East Africa and the South. But the quality of sexual education is not uniform, and it is completely absent in large parts of the continent.

However, the influence of sexual education and the level of education of women may be diluted if the governments and the general public do not support family planning. Even female university graduates cannot produce contraceptives in their pavilion.

It seems that African leaders are gradually recognizing the gravity of the situation. Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni has always opposed family planning, but in July 2014 he hosted a pan-African conference on the need to make family planning more widely available. Government-funded voucher programs in Kenya and Uganda and subsidized maternal and child health services in Zimbabwe encourage low-income individuals and couples to visit clinics. Many of them come away with methods to prevent unwanted pregnancies and increase the time periods between desired pregnancies. In Malawi, transferring funds to pilot programs for school-age girls and their parents or guardians encourages them to come to school, which increases the level of education, delays the onset of sexual activity and marriage, and reduces teenage pregnancies.

The Ethiopian government recently mobilized 38,000 workers to distribute health services, equipped them with information and supplies and sent them to the rural areas where 80% of the country's population lives. When they ride between the remote villages on bicycles, donated by the USA, the health workers offer information about family planning and contraceptives to women, and when there is a response, to their husbands as well. The productivity there has decreased in the last three years from 4.8 to 4.1. No less impressive declines are also recorded in the communities in Kenya and Ghana and even in the super volume of Kinshasa.

However, in many other places in Africa it seems that the presidents of the continent, mostly men, still believe that a family with many children is an advantage and that it is better for women not to strive for equality between themselves and men. "If African presidents visited family planning clinics, it could help," says May. "It could have made a real difference in their approach. But instead of this they always prefer to visit the vaccination clinics."

Changing the men's attitude

Indeed, men in women's lives play an important role. Unfortunately, a leading strategy for helping women plan their families is covert assistance, through birth control injections, for example, and this is because many partners believe that only they, the men, have the right to make decisions regarding childbirth. Men also usually want one to three more children than their wives, which is not so surprising considering that the women are the ones who conceive, give birth and bear the majority of the child care burden.

The difference between men's and women's perspectives sometimes takes on unpleasant manifestations. A woman interested in or using contraceptives may be exposed to abuse from her partner. A study, done in Nigeria and published at a conference in 2011, found that 30% of women, who were married in their lifetime, report some degree of "intimate violence from their partner", sexual, physical or emotional. Women who use contraceptives and women with some elementary education encountered such abuse more than uneducated women and women who do not use contraceptives. Even in Rwanda, despite the great attention given to female empowerment, 31% of women reported in 2010 that their husbands or partners had treated them violently.

Actual violence did not stand in the way of Farida Nlubega when she was 26. She planned to have only two or three children: she thought she would not be able to sustain more than that financially, making a living selling dried fish in Kampala, Uganda, according to PAI, a US-based family planning advocacy group . But she ended up giving birth to six children, and that, she told PAI, was largely because her husband forbade her to use birth control pills and her local family planning clinic offered no suitable alternative.

Attitudes may vary. Men I interviewed on my travels in Africa spoke wistfully of the days when there were fewer people and more forests, and sometimes even expressed support for family planning as a way to slow these negative trends. Most of them also expressed respect for women as partners. "The women in our council see things from a different angle and come up with ideas that none of us would have thought of," a member of a local council in Tanzania told me. "We wouldn't want to give them up now." His statement reflects a broader truth: productivity can also decrease due to what sociologists call "conceptual change": increasing acceptance of concepts that were previously considered extreme and even abhorrent. Tanzania, for example, is considering drafting a constitution that will give women equal status with men in terms of property rights, inheritance and other rights in the law.

Women are also breaking ground and achieving positions in government leadership, which they did not achieve before. Today Rwanda has a minister for gender and the proportion of women in its parliament is the highest in the world: almost two thirds. Joyce Banda, was the president of Malawi from 2012 to 2014. The current president of Liberia is Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. Ngozi Okonjo-Iwela served as Nigeria's foreign minister and finance minister and was the first woman to hold both of these portfolios. The Chairperson of the African Union Commission is Nkoszana Dlamini Zuma from South Africa. When girls see women in these positions, it changes their mindset about the options before them.

Push without pushing

Niger in West Africa is an example of the necessity of an integrated approach supported by government involvement to slow population growth. The average fertility in Niger, one of the poorest countries in the world, is 7.5 children per woman and it has hardly decreased since the data began to be recorded in 1950. In a survey conducted there, women and men said that the ideal family in their eyes is even bigger than that.

Demographers are crazy about it, but this high number is probably due to a combination of several factors. Among them religious belief, high infant mortality, a high proportion of rural residents, who depend on the children's labor in the agriculture they maintain on the poor land. In the eyes of the villagers, a large family reflects status (especially among men) in view of the low status of the woman (children raise the value of the married woman and her husband often has other wives as well). Child rearing is usually shared in the extended family, says demographer John Casterline from Ohio University, which reduces the burden and consequently makes the decision to have another child easier. Mamdouh Tandje, president of Niger until 2010, used to spread his arms to symbolize the vastness of his country, which is larger than the size of Texas, telling visitors that there is enough room for a much larger population.

A multi-pronged strategy requires strong government involvement, community involvement and money, says Gungant, who has worked in West Africa and elsewhere on the continent. But many times governments do not keep their promises. At an international conference in London in 2012, a senior official in Ghana's Ministry of Health promised that his country's national health insurance scheme would provide financial reimbursement for family planning expenses. Four years have passed since then, and the Ghanaian government is still considering how to implement the repayment plan. According to him, the implementation of the plans is "catastrophic. A push is needed, from the government or from civil society or both. In Africa, the push is missing.”

"Pushing" is a charged word for those who fear a mindset of population control. But with the exception of China, where the new two-child policy still limits reproductive freedom, nowhere are there any restrictions on family size. Gungant talks about pushing the leaders to take action: muster courage and put the issue of slowing population growth on the public and political agenda. A zen approach to population art is needed, a way to reduce growth not by directly aspiring to it but by creating the conditions in which it will happen naturally.

Cultures and views can evolve - sometimes quickly, as the decline in productivity in Tunisia and Mauritius shows. Unfortunately, I have no idea what happened to Djanabe from Mali and her hopes of controlling her own pregnancies. But her words are a reminder of the supreme importance of trying to ensure every woman the means and social support to prevent unwanted pregnancies, without coercion and without pressure. Such attempts outline the only moral and practical way to get Africa's population to slow its growth and eventually stop growing, as all populations must do. There, and anywhere else in the world, such populations will be able to live in prosperity, resilience and harmony with the environment.

Women's empowerment does not need demographic justification. But the thing is that women who can aim their ambitions high and manage their lives are women who decide and succeed, to give birth to fewer children and start doing so at a later age. Even if population growth were not important, the future of Africa and the future of the world would be better if every girl and every African woman were healthy, educated and free to fulfill her ambitious dreams, to refuse, without fear, unwanted attention from men and to give birth to a child only when and with whom she is wants to.

The question of whether Africa will reach the end of the century with a few billion people or with a number much closer to its current population, 1.2 billion, will greatly affect its development, its prosperity, and its ability to withstand the challenges that will undoubtedly lie ahead.

6 תגובות

The white man tells Africans what is good for them. This time, according to the teachings of environmentalism and progress that he invented. Meanwhile, Europe is aging and shrinking at 1.5 births per woman. A person who is not a hypocrite enlightened racist, will be happy about the number of blacks in the world and the death of European whites by self-destruction due to infertility.

The white man tells Africans what is good for them. This time, according to the teachings of environmentalism and progress that he invented.

To me it is incredibly strange that "demographers are crazy" about the high birth rate in Niger.

Demographers? People who have really studied the conditions in Niger and manage to ignore the fact that literacy among the women there is 11%. In words: eleven percent, the lowest figure in the world, many years lower than the second place in its misery!

And what about the arrogant and superficial prejudices of types like you? How will we deal with loud people like you who do not understand what they are talking about and in what context?

What about the empowerment of women in the religious sector and the ultra-orthodox sector and the Arab sector. And how will they face the calls of the imams and rabbis to do the opposite of that.

Successfully. Looks like a lost war.