Trials may provide treatment for retinal detachment

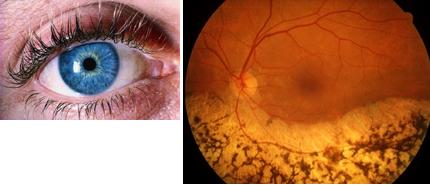

On the right, an eye of a patient with retinitis pigmentosa. Left: A healthy eye

An injection of stem cells saved the sight of a mouse that would have gone blind without the treatment, scientists report. The research raises the possibility that some forms of human blindness will be treated in the future by stem cells taken from the patients' bone marrow.

The research group focused on a group of eye diseases known as retinitis pygmatosis, in which cells in the retina break down over time, causing a gradual loss of vision and sometimes even blindness. For now, there is no adequate treatment for the syndrome, which affects approximately 3,500 people.

Martin Friedlander at the DeCripps Research Institute in La Jolla California and his group extracted a pool of stem cells from the bone marrow of adult mice and injected them into the eyes of newborn mice with a version of retinitis pigmentosa, before their retinas began to break down. The injections seem to have stopped some of the deterioration of the eye, especially regarding the cone cells, which are responsible for color vision and other features.

The treated mice were also able to respond and follow light directed into their eyes, while the control group, which consisted of mice that did not receive the treatment, became completely blind. "It's amazing," says Friedlander, who reports the results in a clinical research journal.

A variety of other cell types can develop from stem cells, but it is not yet known how they help the eye in this case. The research group previously showed that stem cells can help stop retinal blood vessels from disintegrating, possibly by integrating into them. However, it is possible that other stem cells do not help in the restoration of the blood vessels, but settle in the eye and produce types of molecules that help both the blood vessels and the cone cells to survive.

Friedlander hopes that the vision of human patients with retinitis pigmentosa will be preserved by injections of their own stem cells, cells harvested from the patients' bone marrow. In humans, the deterioration of the eye does not tend to begin until puberty or even later. "We turn to the clinic with the results of the experiment" he says. He hopes to start using this technique on human patients in a year or so, if he can gather enough evidence that the technique described here is safe enough.

The technique is one of the most promising treatments for blindness discovered in recent years, agrees Lewis Smith, who studies ophthalmology at Harvard University in Massachusetts. Retinitis pigmentosa has many causes, so it is difficult to find a single drug that will work in all cases.

It may be possible to use stem cells for other, more common cases of blindness, the researchers estimate. The most common cause of blindness is diabetic retinopathy as well as age-related macular (macular) destruction. In both of these conditions blood vessels in the eye grow abnormally. It may be possible to engineer the stem cells to produce molecules that repair blood vessel growth, Smith says.

Information about retinitis pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa is a hereditary disease of the retina in which specific photoreceptor cells, the rods, degenerate and break down. The loss of function of these cells reduces the patient's ability to see in dim light and over time can cause a reduction in peripheral vision. Probably mutations in at least ten different genes cause retinitis pigmentosa. The first gene responsible for the disease was discovered in 1989, when Irish researchers found that the mutation that caused the disease in a large Irish family was near the rhodopsin gene. After that, researchers from Harvard discovered a specific mutation in rhodopsin and later, following the development of a test to identify mutations in the rhodopsin gene, more than fifty different mutations in the rhodopsin gene were discovered, each of which causes retinitis pigmentosa.

The retinal appearance of a patient with retinitis pigmentosa which was caused by a mutation in the rhodopsin gene. The brown pigment in the lower half of the eye is the finding that gave the syndrome its name. The sharp demarcation between the normal retina in the upper part and the abnormal retina in the lower part is characteristic of rhodopsin mutations.