Rosalind Franklin's research was leaked by her lab partner at King's College London, Maurice Wilkins to Francis and Crick and helped them discover the structure of DNA

More on the same topic on the science website

- Rosalind Franklin - the story of a famous scientific discovery and a forgotten woman

- "Deciphering the book of life - sixty years since the discovery of the structure of DNA"

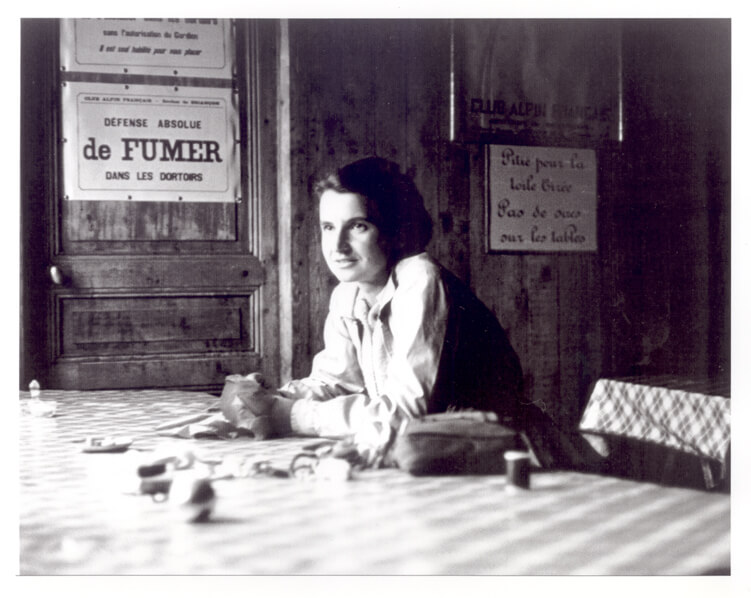

Today marks the 93rd birthday of Rosalind (Rachel) Franklin (1920-1938) was a British chemist and crystallographer best known for her role in discovering the structure of DNA which was unknowingly passed on to those who eventually received the Nobel Prize for her - Watson and Crick. It was the X-ray diffraction photographs of DNA and the data analysis of her research that were unbeknownst to Francis Crick and James Watson that gave them vital clues to building the correct theoretical model of the molecule in 1953.

Rosalind Franklin always liked the facts. She was logical and precise, and impatient when things were done differently. She decided to become a scientist when she was 15. She passed the Cambridge University entrance exam in 1938, triggering a family crisis.

Although her family was affluent and had a tradition of public service and philanthropy, her father opposed university education for women. He refused to pay her tuition. Her aunt intervened and said that Franklin should go to university and was willing to pay for her. Franklin's mother stood by her side until her father finally gave in.

When the war broke out in Europe, in 1939, Franklin was in Cambridge. She graduated in 1941 and began working on her Ph.D. Her work focused on a problem related to war as she investigated the nature of carbon and other forms of carbon and how to use them most effectively. She published five articles on the subject before she turned 26. Her work is still cited today, and helped launch the field of reinforced carbon fibers - one of the important derivatives of the field of nanotechnology.

After the war, Franklin completed her Ph.D. She began researching X-ray diffraction - using X-rays to create images of solid crystals. She pioneered the use of this method in the analysis of complex and disorganized materials such as large biological molecules, and not just single crystals.

She spent three years in France, enjoying the work atmosphere, the freedoms of peacetime, the French food and culture. But in 1950, she realized that if she wanted to pursue a scientific career in England, she had to return. She was invited to King's College London to join a team of scientists studying living cells. Franklin's assumption was that it was her project. The other person in charge of the lab, Maurice Wilkins, was on vacation at the time, and when he returned, their relationship was in turmoil. He assumed she came to help his work, she assumed she was the only one working on the DNA. There were big personality differences between them. Franklin was direct, quick, decisive, while Wilkins was shy, speculative, and passive.

Franklin made considerable progress in X-ray diffraction techniques with DNA. She set up her camera equipment and created an extremely fine beam of X-rays. She produced finer DNA fibers than ever before and arranged them in parallel bundles and studied the reactions of the fibers to humid conditions. All these allowed her to discover essential clues about the structure of DNA. Wilkins shared her data without her knowledge

With James Watson and Francis Crick, also from Cambridge University, they pulled ahead in the race, eventually publishing the proposed structure of DNA in March 1953.

The strained relationship with Wilkins and other factors that harmed her at King's College (the women scientists were not allowed to eat lunch in the common dining room with the men) led Franklin to look for another position. She headed her research group at Bickerback College in London, but the head of King's College agreed to let her leave only on the condition that she not work on the DNA. Franklin returned to carbon research and also continued her work in the field of DNA, but this time she turned her attention to viruses, she spent the last five years of her life studying the structure of viruses that attack plants, and in particular the virus that causes tobacco mosaic. Franklin published 17 papers in five years. Her group's findings laid the foundations for the field of structural virology.

When she went on a professional visit to the United States, Franklin felt pain that later turned out to be caused by ovarian cancer. She continued to work for the next two years, through three rounds of experimental chemotherapy, enjoying a ten-month reprieve. She worked until a few weeks before her death in 1958 at the age of 37.

5 תגובות

Obviously, the award was taken from her. And in the ugliest, wretched, devious way.

The award was taken from Rosalind Elsie Franklin, in blessed memory,

By two cheating, wretched, lying men who belong in prison.

They didn't correct the date of death!?

Please correct the year of death in the top row

The title will be corrected

Eitan Crane's response on the site's Facebook page

For some reason I can't comment on the website so I will comment here. The Nobel Prize was awarded to Watson and Crick in 1962 after Franklin's death. According to the prize regulations, it is not possible to give a Nobel Prize to a dead person. So the title is misleading. Maybe her fame was stolen but certainly not the prize.