The book was published by "Aliyat HaGeg Books and Yediot Books". From English: Dafna Levy. * The subchapters: "The Exit from the Darkness", and "The Elegance of Copernicus"

The exit from the darkness

The Renaissance is the period when the people of Western Europe lost their respect for the ancients and realized that they could contribute to civilization and society no less than the Greeks and Romans did. To modern eyes, the bewilderment is not that this happened, but that it took so long for the people to free themselves from their inferiority complex. The detailed reasons for this great delay are beyond the scope of this book, but anyone who has visited the sites of classical civilization around the Mediterranean can take a look at the things that made people in the "dark" Middle Ages (roughly speaking, AD 900-400), and even in the days of Late Middle Ages (1400-900), to feel as they felt. Buildings such as the Pantheon and the Colosseum in Rome inspire awe even today, and in the days when all the knowledge to build such buildings was lost, they probably looked as if they were built by another species of humans - or by the hands of gods. With so many physical evidences of the supposed divine ability of the ancients, and with the rediscovery of texts that came from Byzantium, proving the intellectual ability of the ancients, it was only natural to believe that intellectually they were far superior to the ordinary mortals who came after them, and to accept the teachings of the ancient philosophers Like Aristotle and Euclid as if they were Torah from Sinai. Since the Romans contributed very little to the discussion that today we would call a scientific view of the world, during the Renaissance the conventional wisdom about the nature of the universe remained almost unchanged since the great days of ancient Greece, about 1,500 years before Copernicus appeared on the scene. And yet, once the truth of these ideas was questioned, progress was incredibly fast - after 1,500 years of stagnation, less than 500 years have passed from the time of Copernicus to the present day. It may sound like a cliché, but it is nevertheless true to say that a typical tenth-century Italian would have felt at home in the fifteenth century as well, but a fifteenth-century Italian would have found the twenty-first century less familiar to him than Italy in the days of the Roman Empire.

The elegance of Copernicus

Copernicus himself was an intermediate figure in the scientific revolution, and in one important respect resembled the ancient Greek philosophers more than the modern scientist. He did not perform experiments nor did he make his own observations of the sky - at any rate, not to any significant extent - and did not expect anyone else to try to put his ideas to the test. His big idea was only an idea, or what today is sometimes called a "thought experiment", which presented a new and simpler way to explain the same pattern of behavior of the heavenly bodies that was explained using the more complicated method invented (or published) by Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemy). If a modern scientist has a bright idea about how the universe works, his first goal will be to find a way to test the idea through experiment or observation, to find out how successful it is as a description of the world. But the key step in the development of the scientific method was not made in the fifteenth century, and it never occurred to Copernicus to test the idea he came up with - his mental model of the way the universe works - through new observations that he himself would make, or to encourage others to make new observations. To Copernicus, his model was better than Ptolemy's because it was, in modern terms, more elegant. Elegance can often be a reliable touchstone of a model's usefulness, but it is not infallible. However, in this case it turned out in the end that Copernicus' intuition was correct.

There is no doubt that Ptolemy's method lacked elegance. Ptolemy (sometimes called Ptolemy of Alexandria) lived in the second century AD and was educated in Egypt, which has always been under the cultural influence of Greece (as the very name of the city where he lived according to the records). Very little is known about his life, but among the works he left for posterity was a large treatise on astronomy, based on 500 years of Greek astronomical and cosmological thought. The book is generally known by its Arabic name, Almagest, which means "the greatest", and it gives some idea of its status in the following centuries; Its original Greek title simply describes it as a "mathematical collection". The astronomical method he describes is far from being Ptolemy's own idea, although he seems to have modified and developed the ideas of the ancient Greeks. However, unlike Copernicus, it seems that Ptolemy himself made extensive observations of the movement of the planets in addition to what he drew from the observations of his predecessors (he also drew important star maps).

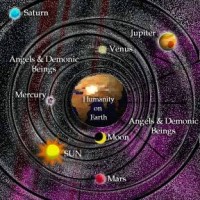

The basis of Ptolemy's method was the idea that the heavenly bodies must move in perfect circles, simply because circles are perfect shapes (here is an example of how elegance does not necessarily lead to truth!). At that time five planets were known (the planet Mercury, Venus, Mars, Saturn and Jupiter), as well as the Sun, the Moon and the stars. In order for the observed movements of these celestial bodies to conform to the requirement of perpetual motion in perfect circles, Ptolemy had to make two major revisions to the basic idea that the Earth is at the center of the universe and everything else revolves around it. The first correction (which was thought of long before) was that the motion of a certain planet could be described as turning in a small perfect circle around a point which itself circled in a perfect circle around the Earth. The small secondary circle (a kind of "wheel within a wheel") is called an epicycle. The second correction, which was probably perfected by Ptolemy himself, was that the great crystal spheres, as they were known in Shemmen ("crystal" in this context simply means "invisible"), which carry the heavenly bodies around in circles, do not actually revolve around the earth but around a set of slightly deviated points from the earth and are called "equant points", which differ from one celestial body to another. The earth was still considered the central object in the universe, but everything else revolved around aquant points, not around the earth itself. The large circle centered at the aquant point is called a deferent.

The model proved itself in this respect that it could be used to describe the apparent movement of the sun, the moon and the planets against the background of the planets of Saturn, i.e. the fixed stars (fixed in the sense that they all kept the same pattern while moving together around the earth), which themselves were considered connected to the sphere In a crystal outside the system of the crystal balls that carried the other celestial bodies around the relevant aquant points. But no attempt was made to explain the physical processes that drove everything in this way, nor to explain the nature of the crystal spheres. Furthermore, the method was often criticized as being too complicated, while the need for aquant points caused discomfort among many thinkers - this raised doubts about the assertion that the earth is the center of the universe. There was even a hypothesis (already put forward by Aristarchus in the third century BC, and it came up again and again in the centuries after Ptolemy) that the sun might stand at the center of the universe, and the earth revolved around it. But such ideas did not find favor, mainly because they stood in open contradiction to "common sense". Of course, it is impossible for the solid earth to move! This is one of the clear examples that one must be careful not to rely on common sense if one wants to know how the world works.

Two specific things pushed Copernicus to propose something better than Ptolemy's model. First, each planet, in addition to the Sun and the Moon, requires a separate reference in a model that takes into account its own offset from the Earth and its own epicycles. There was no comprehensive and consistent description of things that would explain what was happening. Second, there was a specific problem that people had been aware of for a long time, but usually swept it under the rug: the offset of the Moon's orbit from the Earth, necessary to account for the change in the apparent speed of the Moon's movement across the sky, was so great that the Moon was considered much closer. to the land on certain days of the month compared to other days - so that apparently its size must change considerably (and can be calculated), which clearly did not happen. In a sense, since Ptolemy's method does provide a prediction that we could test with observations, it fails this test and is therefore not a good description of the universe. Copernicus didn't think exactly so, but the moon problem must have prevented him from accepting Ptolemy's method.

Nicolaus Copernicus entered the picture at the end of the fifteenth century. He was born on February 19, 1473 in the Polish city of Torun on the banks of the Vistula River, and was first called Nicolaus Copernicus, but later changed his name to Latin (a common practice at that time, especially among the humanists of the Renaissance). His father, a rich merchant, died in 1483- or 1484-, and Nikolaus grew up in the house of his mother's brother, Lukas Wachenrode, who was appointed bishop of Ermland. In 1491 - (only a year before Christopher Columbus's departure for his first voyage to the New World), Nikolaus began his studies at the University of Krakow, and then discovered - probably for the first time - a serious interest in astronomy. In 1496 he moved to Italy and studied law and medicine there in addition to normal classical studies, and mathematics in Bologna and Padua, before receiving a doctorate in ecclesiastical law from the University of Ferrara in 1503. Copernicus, befitting a man of his time, was largely influenced by the humanist movement in Italy and studied the classical studies associated with this movement. Indeed, in 1519 he published a collection of poetic letters by the writer Theophilus Simocata (a seventh-century Byzantine), which he translated from the Greek source into Latin.

When Copernicus completed his doctorate, his uncle Lukas already appointed him a priest at the Frombork Cathedral in Poland - a clear case of nepotism that arranged for him a comfortable and lucrative position, which he held until the end of his days. But only in 1506 did Copernicus return permanently to Poland (which gives us an idea of how few the job requirements were), where he worked as his uncle's doctor and as his secretary until Lucas's death in 1512. After the death of his uncle, Copernicus paid more attention to his duties as a man of religious law, he practiced medicine and held junior civil positions, which nevertheless left him more than enough time to persist in his interest in astronomy, but his revolutionary ideas about the place of the earth in the universe had already taken shape by the end of the first decade of the sixth century ten.

Tomorrow, the third and final part of the book: the continuation of the work of Copernicus

The introductory chapter to the book "The History of Science" by John Gribbin

9 תגובות

I don't think the Renaissance period was so "rebellious" in the "Dark" Middle Ages...

All the approaches present in today's research range from historians such as Johann Hauzinha and members of the Warburg Institute (Zacksel, Bing, Gombrich, Witkober, Cassirer, Yates) to contemporary historians (Grafton), especially Jews (Bonfil, Ruderman) and Israelis (Adelheit).

These scholars saw the long-term influence of the classical works and how they were re-received in the Renaissance, but argued that the apparent break with this lies in later scholasticism. At the same time, a similar process was carried out in Judaism mainly by the students of the late Prof. Shlomo Pines and Prof. Yosef Baruch Sarmonita of the Thought of Israel and the late Prof. Haim Hillel Ben Sasson of the History of Israel, mainly by those known as the Bonfil school (Weinstein, Perry, Weinberg, Krakotskin and more) .

Even in the history of science from Pierre Duham to Alistair Crombie and even the late Israelis Amos Funkenstein and Yehuda Elkana, and the late Rivka Peladhi and Michael Head, they have already begun to understand that the disconnection was extremely slow, and perhaps there was actually a step-by-step growth and the use of concepts from the religious world that underwent a secularization process.

"The Renaissance is the period when the people of Western Europe lost their respect for the ancients and realized that they could contribute to civilization and society no less than what the Greeks and Romans contributed."

This sentence comes down hard here, but it is true if you understand it correctly (perhaps the writer or the grammarian did not polish the wording enough). I will try to explain by reading this entire chapter in the book - the meaning is that by the end of the Renaissance, individual people (who sowed the seed for the continuation) lost their sense of dignity and saw that they could contribute. It's actually a process that went on and on when at the beginning of the Renaissance there was actually great respect and the writings of the Greeks were treated as almost holy scriptures.

Later he brings a quote from a book by Gilbert from 1600 that really shows the loss of that respect and the emergence of a new school of thought:

"In the discovery of the secret things and the investigation of the hidden causes, stronger reasons are obtained from safe experiments and demonstrable reasons than from probable hypotheses and the opinions of philosophical speculators."

Gilbert was a trailblazer, Galileo was influenced by him and from here science as we know it today began.

Reading the book now. In the meantime, he is having fun and is educated, although there are sections where he stretches like chewing gum.

What a boring book on an interesting topic

True, alive.

It is also only because of our limitations that we divide the body into hands, feet, head, body, blood, nerves, muscles, bones, etc. We had to call everything a body and that was it.

In general - why define a body as well. There are many people so we will not define each one separately. We will overcome our disability and call everything humanity.

But why stop here?

Let's also ignore the differences between people and other animals and between animals and plants and between the living and the inanimate and all the differences and refer only to one thing we call "everything".

This is a sure way to reach the desired nothingness.

The Renaissance is neither a revival of the past nor an annulment of the past, it is a direct continuation that, due to our limitations, we divide into periods. Even in the Middle Ages there were small renaissances.

"The Renaissance is the period when the people of Western Europe lost their respect for the ancients and realized that they could contribute to civilization and society no less than what the Greeks and Romans contributed."

If this is how the book opens... there is something wrong with it!

The Renaissance is a revival of the past, not its cancellation or loss of reverence. The people of the Renaissance came out of the darkness of the Middle Ages and the regime of thought imposed by the church and built with their own hands a glorious present and future on the basis of human heritage. The "ancients", the sages of ancient Greece, as well as other cultural heritages inspired them. They did not cancel the influence of ancient sages - rather they rediscovered it!

I think that today it is difficult for us to understand the boldness of Copernicus' words, well then the earth is not at the center of the universe so what? The audacity of Cuprincus's words was the claim that the earth moved. We all know from day to day that when we move we feel it, the wind is blowing in our face and we have to make an effort to move. How could it be claimed that the earth actually moves and we do not fall from it? To understand this, we must forget our everyday logic, our feelings and experiences and imagine a world without friction, all this in order to present a more elegant mathematical model that describes the movement of the planets...